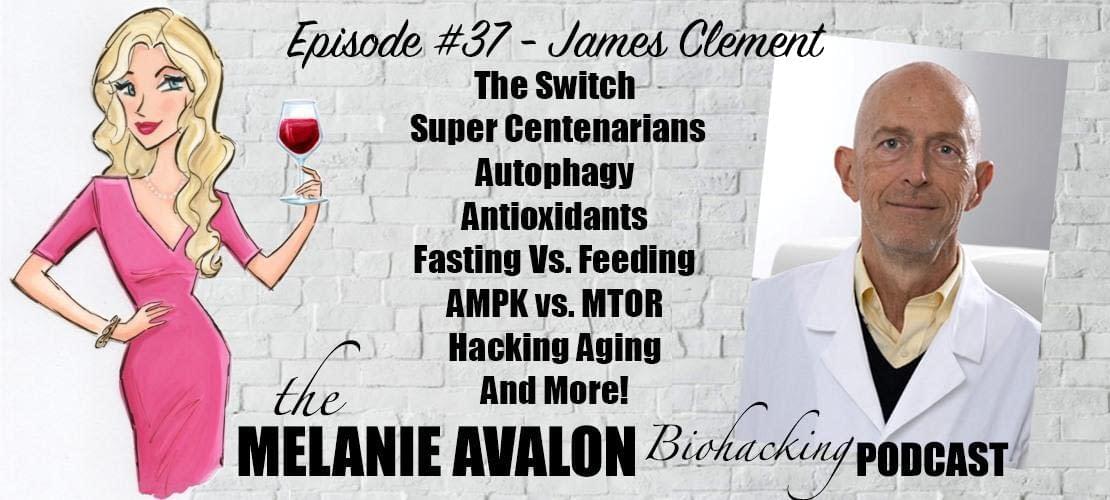

The Melanie Avalon Podcast Episode #37 - James Clement

James W. Clement is a lawyer and entrepreneur turned research scientist who has devoted the last two decades to understanding the science of life extension. He is best known for his Supercentenarian Research Study, which he started in 2010 with Professor George M. Church of Harvard Medical School and has received international press coverage, including features in the NY Times and London Times. Through worldwide scientific collaborations and in his own laboratory, James focuses on advancing cutting-edge biomedical discoveries. He is the founder of the nonprofit Betterhumans biomedical research organization. Led by a collection of high-profile researchers, the organization focuses on bringing cutting edge scientific discoveries from the lab to the clinic. Clement was the 12th person in the world to have his whole genome sequenced and is Personal Genome Project participant #145 (ID: hu82E689).

LEARN MORE AT:

jameswclement.com, betterhumans.org

SHOWNOTES

The Switch: Ignite Your Metabolism with Intermittent Fasting, Protein Cycling, and Keto

2:00 - Instagram Giveaway: Follow @MelanieAvalon And Comment Your Favorite Biohack To Enter To Win A Signed Copy Of The Switch!

2:25 - Paleo OMAD Biohackers: Intermittent Fasting + Real Foods + Life: Join Melanie's Facebook Group To Discuss And Learn About All Things Biohacking! All Conversations Welcome!

2:40 - LISTEN ON HIMALAYA!: Download The Free Himalaya App (Www.Himalaya.Fm) To FINALLY Keep All Your Podcasts In One Place, Follow Your Favorites, Make Playlists, Leave Comments, And More! Follow The Melanie Avalon Podcast In Himalaya For Early Access 24 Hours In Advance! You Can Also Join Melanie's Exclusive Community For Exclusive Monthly Content, Episode Discussion, And Guest Requests!

2:50 - Get David Sinclair's Email Newsletter: The Lifespan Insider

3:40 - FOOD SENSE GUIDE: Get Melanie's App To Tackle Your Food Sensitivities! Food Sense Includes A Searchable Catalogue Of 300+ Foods, Revealing Their Gluten, FODMAP, Lectin, Histamine, Amine, Glutamate, Oxalate, Salicylate, Sulfite, And Thiol Status. Food Sense Also Includes Compound Overviews, Reactions To Look For, Lists Of Foods High And Low In Them, The Ability To Create Your Own Personal Lists, And More!

5:30 - James Unconventional History And Health Revolutions

9:40 - The Studies In Super Centenarians

14:15 - Genetic Mutations, Lifestyle Practices, And Environment For Longevity

21:30 - The Role Of Diet In Longevity

23:15 - The Changeability Of The Gut Microbiome

Hunter-gatherers' seasonal gut-microbe diversity loss echoes our permanent one

29:30 - What Is Autophagy And MTOR Why Is It Important For Longevity?

34:45 - Does Autophagy Require Lifestyle Intervention?

37:40 - The Different Routes To Autophagy, And Long Lived Populations Long Lived (Okinawa, Loma Linda, Mount Athos Monks)

42:00 - Modern Diets Like Carnivore, Elimination Diets, And The Role Of Protein In Longevity

46:30 - The Problem With HCHF

48:30 - DRY FARM WINES: Low Sugar, Low Alcohol, Toxin-Free, Mold- Free, Pesticide-Free , Hang-over Free Natural Wine! Use The Link DryFarmWines.com/melanieavalon To Get A Bottle For A Penny!

49:30 - The Switch: MTOR, AMPK, And Autophagy

51:40 - Fasting And Calorie Restriction: Overlapping Or Additive?

55:00 - The Different Types of Autophagy

53:20 - Are The Benefits Of IF Just Due To Calorie Restriction Or Weight Loss?

56:20 - The Fasting Mimicking Diet 4:20

58:15 - Combating CR Effects With Exercise

1:01:20 - Fasting Forever And The Need For Cycling

1:03:00 - Daily Vs. Monthly Cycling And Genetic Expression

1:08:15 - Habitual Hunger, Energy Cues , And Retraining Cells With Keto Or Extended Fasts

1:11:30 - Carbs, Comfort Foods, Dopamine and Serotonin From The Gut

1:13:30 - AMPK Activators

Quicksilver Scientific's Keto Before 6 (Use The Link MelanieAvalon.com/Quicksilver For 10% Off!)

1:17:00 - BLUBLOX - Blue-light Blocking Glasses For Sleep, Stress, And Health! Go To BluBlox.com And Use The Code melanieavalon For 15% Off!

1:19:45 - JOOVV: Red Light And NIR Therapy For Fat Burning, Muscle Recovery, Mood, Sleep, And More! Use The Link Joovv.Com/Melanieavalon With The Code MelanieAvalon For A Free Gift From Joovv, And Also Forward Your Proof Of Purchase To Contact@MelanieAvalon.Com, To Receive A Signed Copy Of What When Wine: Lose Weight And Feel Great With Paleo-Style Meals, Intermittent Fasting, And Wine

1:21:15 - Gluconeogenesis, Cortisol, Stress, And Blood Sugar

1:27:30 - Elevated Blood Sugar Levels On Low Carb, Elevated Blood Sugar, Aging , And Disease

1:30:20 - Endogenous Vs Exogenous Antioxidants, DNA Breaks, NAD, And The Dark Side To Antioxidants

1:38:25 - Antioxidants While Fasting

1:43:22 - NR and NMN Supplementation

1:50:05 - BEAUTY COUNTER: Non-Toxic Beauty Products Tested For Heavy Metals, Which Support Skin Health And Look Amazing! Shop At Beautycounter.Com/MelanieAvalon For Something Magical! For Exclusive Offers And Discounts, And More On The Science Of Skincare, Get On Melanie's Private Beauty Counter Email List At MelanieAvalon.Com/CleanBeauty!

Quicksilver Scientific's NAD+ Gold (Use The Link MelanieAvalon.com/Quicksilver For 10% Off!

1:51:45 - The Hermetic Potential Of Low Dose Toxic Exposure

1:58:30 - Are We Programmed to Start Aging At 25?

From Dr. Michael Ruscio's Healthy Gut Healthy You:

NOTE: The Sardinia population started experiencing more multiple sclerosis after the malaria-eradication program."In the 1950s, Sardinia underwent a malaria-eradication program that virtually eliminated this infection from the population. Since then, Sardinia’s rate of the autoimmune disease multiple sclerosis (MS) has skyrocketed. Here’s what we think happened: The Sardinian immune system evolved to be strong under the constant pressure from malaria. Once malaria was gone, the strong immune system didn’t know what to do. It was so used to being in a constant battle with malaria that once malaria was gone, it started attacking the Sardinian nervous system tissue, causing MS."

2:06:30 - Instagram Giveaway: Follow @MelanieAvalon And Comment Your Favorite Biohack To Enter To Win A Signed Copy Of The Switch!

TRANSCRIPT

Melanie:

Hi friends. Welcome back to the show. So I am very, very excited about the conversation that I am about to have today. It is with James Clement. He is the author of a new book called The Switch: Ignite Your Metabolism with Intermittent Fasting, Protein Cycling, and Keto. And listeners, just hearing that title, you can probably tell why I'm so excited. Because so many topics here, everything I'm obsessed with. Longevity, factors that affect that, genes, diet. And James' book The Switch is, I mean it's really, really wonderful. It's comprehensive. It goes into the history of humans, the diets that we followed. How things like genes and our different habits affect longevity. I mean it's a fascinating read. It's also a very approachable read. I know a lot of these topics can get a little bit intense at times, but it's easy to read. I learned so much reading it. So I am just really, really excited for the conversation that we're about to have. So thank you so much James, for being here.

James Clement:

Thank you very much for inviting me. I'm really excited about this discussion.

Melanie:

Yeah. And James, so you have a really interesting background. So you are a lawyer and an entrepreneur turned research scientist with a passion of exploring the science of life extension. So would you like to tell listeners a little bit about your personal history and what made you become a research scientist?

James Clement:

Sure. And it would probably take an hour to go through all the history of how I decided to be a lawyer rather than a scientist. Because I actually worked on a big project in college, put about 3,000 hours into it that got published in Science. And the professor I worked with said he could arrange a full scholarship to University of Chicago Med School if I would continue in that field. And I said, "No thanks, I'm going to pay for law school myself." And did that.

James Clement:

But in my third year of law school, this incredible book came out by Durk Pearson and Sandy Shaw called Life Extension: A Practical Scientific Approach. This is 1981-'82 time period. And I read that, and it was basically what we would now call a biohacking book. It was 900 pages of molecular biology and how to hack it for better health and lots of cognitive, sexual improvement, whatever. All covered in this book. And it really kind of launched me into this idea that aging and your health, you could intervene into this by whatever you did yourself. And the more you knew, the more you could do. So it sort of launched me into this lifelong project of learning about molecular biology and how we can hack it.

Melanie:

I love that so much. It's crazy how you can read something or just be exposed to this new paradigm way of thinking, and just become so obsessed and want to learn so much. I mean I know that's what happened with me personally.

James Clement:

I think a lot of us. And from what I understand, you fit in this category as well. Had health issues, which also pushed us into learning more about our own personal biology and what was wrong with this, how to fix it. I can certainly relate to that aspect. And when I was practicing law in New York, I actually had gotten chicken pox for the first time in my life when I was 30 years old. And the virus affected a lot of things including my memory was really terrible. And I had partners later when I was leaving the New York firm I was with say, "Yeah I'm sorry I never got to know you but I was sure you were going to die." So things like that. Also, I think Dave Asprey has a very similar story. I've heard this repeatedly from doctors and other people who are interested in health span and longevity is that they also either themselves or had someone close to them have a problem that they needed to sort of delve into.

Melanie:

Yeah, 100%. That is so true. Because it's like when your body is functioning seemingly great or you're not experiencing any sort of indicator that things might be wonky, I think it's easy to just, you're not paying attention to necessarily how to optimize things because things already seem to be going okay. But then when things are not going so well, then you start trying to find the answers. And then at least for me, and it sounds like for you as well, then you start realizing all of these factors that are affecting things. And you just realize there's so much going on. And at the same time, like you said with the biohacking and such, you start to realize that in addition to perhaps correcting where your body might have gone off course, that there's also this potential to optimize beyond that.

Melanie:

So yeah, I've had my own health struggles and issues. But in a way I'm sort of grateful for them because I wouldn't even have this podcast honestly if that hadn't happened. Because it's really just come out of a relentless search to just try to learn more and figure out what's actually happening. So sounds like we can relate there for sure.

Melanie:

One of the things you talked about in the book that I loved, and this was one of the things that you opened with. Was the research that you had done on supercentenarians and what you had seen in their blood work. I found this really, really fascinating. So I was wondering if you could tell listeners a little bit about your studies and your research that you did there and what you found.

James Clement:

Sure. So in 2009, I was on the board of directors of a startup company that the geneticist at Harvard Medical School George Church was involved with called Knome. It was the first direct to genome sequencing company. So I got to have George Church actually read my own personal genome results or interpretation to me. And I was interested in anti-aging. And I found out that George was as well. So I talked to him for about a year about ideas that I had for setting up a biotechnology company and intervening into aging. And one of them was that we would use some gene editing techniques to iteratively improve our own stem cells. So our stem cells, we take them out of us, we would make some genetic improvements, we would put them back into us. And he said, "Well James, that's a really great idea and increasingly practical. But we don't know which genes to change." So I went away from that thinking okay, how do we figure out which genes to change? And I had been reading the work of these really great researchers Tom Perls, Nir Barzilai and Stewart Kim. And they were doing a different form of gene sequencing in the centenarians and supercentenarians. And coming up with some really interesting anti-aging gene information. And I thought well why don't we do whole genome sequencing? Since I was involved in a company that did this.

James Clement:

So I went back to George and proposed this project, and got IRB approval. And for the next four or five years, really went around the world collecting blood samples from people that were 106 years and over. So a supercentenarian is someone who has lived to at least 110. And I met eventually 60 people in this age group and got them to agree to allowing us to have a blood sample from which we could take and sequence their DNA. And in 2017, we got them all sequenced and made the database available through my nonprofit organization, to any researcher that wants to use that for whatever projects they're working on. So we got like a dozen really major universities around the world using these supercentenarian genomes to look at things like disease prevention and healthy longevity.

James Clement:

They were absolutely amazing, and I could certainly talk to you for hours about these particular individuals. Because they're just incredibly memorable characters. We're talking about 111 year olds that the nurses are saying, "Yeah, he still pinches people's bottoms." Guys that are still living on their own and driving their own cars at 106, 107 years old. So really incredible group of people.

James Clement:

If you want to go into some of the actual anti-aging factors, it actually ties into the book very well. Because one of the things that we found is that there are loss of function mutations that these people have. That essentially give them naturally what you and I would have to do by fasting, calorie restriction, or some kind of severe intervention. That they get naturally just because that's how their genes are wired. So a lot of this has to do with the mTOR autophagy pathway that we'll talk about later. And sort of as similar to the restricted IGF-1 that you see in dwarf mice and miniature versions of animals. Where they have smaller body types but they live much longer than the full-sized version of the same species. So it's really interesting that this group is actually a living example of many of the things that I talk about in the book.

Melanie:

Super quick question. Did literally every single supercentenarian have some sort of genetic mutation that supported this, or were there even outliers?

James Clement:

No, there's lots of outliers. And we certainly haven't delved to the depths of what these genetic mutations are. Some of them are gain of function. So there's some transcription factors that improve like the number of mitochondria that you would have. But the ones that have been identified, and we certainly see overrepresented in the population of centenarians and supercentenarians, are the ones related to growth hormone and IGF-1. And again, this makes total sense because I would say almost all of the supercentenarian men and women that I met were actually quite diminutive. Five foot, five foot two individuals. And this is sort of what you would expect if they didn't have the high levels of IGF-1 that you would expect people to have today.

Melanie:

Okay. That is fascinating. So basically, they have these genetic mutations that naturally create for them in a way the effects that various lifestyle practices that we'll probably be talking more about. So we often think that various lifestyle practices support longevity, but it seems that with these lucky lottery winners supercentenarians, it's like their body is automatically creating these effects without necessarily the lifestyle practices. How often did the supercentenarians actually follow the type of lifestyle practices that we might assume would lead to longevity compared to not really engaging in any of that? How did that line up?

James Clement:

So I only know one out of the 60 who specifically was sort of what we would have called 10 years ago, a health nut. Meaning that he really watched what he ate. He did yoga. His son got him to stop doing headstands. So he would prop himself up on the corner and invert himself in a handstand and then lower himself. So he was just resting on his head, until he was like 106. His son finally said, "Enough's enough dad. I don't know if this is safe to continue doing."

James Clement:

But most of them had very ordinary lives in terms of they weren't specifically trying to be healthy, they weren't specifically doing healthy things. As you probably know, Jeanne Calment smoked for 100 years. Many of the men supercentenarians especially the two most prominent American supercentenarians, Walter Breuning and another gentleman I'm not thinking the name of. They both smoked cigars up until past 100 years of age. And again, usually only stopped because they went into nursing homes and their doctors at the nursing homes were saying, "This isn't good for you," even though they've made it to 107 or eight years old already smoking several cigars a day.

James Clement:

So genetics plays a very important part in those people's lives. But I think for the rest of humanity that doesn't have the advantage of these genetic lottery wins, so to speak. For us it's going to be almost 100% environmental. You see various figures. In the book I talk about, it's about 80% environmental and 20% genetics. But when you think about it, even have it like I do. A genetic propensity towards type 2 diabetes. You can simply hack your own diet, change your lifestyle, and greatly reduce your chance of type 2 diabetes. And this is true, I think for a very large number of the single nucleotide polymorphisms that give an increased risk to disease, is that there's also lifestyle changes that you can make. More exercise, different diets. If you have MTHFR mutation where you lose the methylation donors, then you can simply take methyl donor compounds. So I think we're learning more and more how to hack even the genetic problems that we have so that it becomes nearly 100% environmental, in the sense that you can affect the ultimate outcome.

Melanie:

I'm so fascinated by this. Because I mean that was something I had always picked up on was that super centenarians, you look at their diets and their lifestyles. And it seems that so often it's like what you just said. It wasn't really the healthy diet, exercising a million times a day. It was more just the sense of loving life and things were going really great. And I was, until this conversation actually right now, was just assuming that it was a mindset thing. So that was the primary factor driving longevity. And then perhaps genes. But now I'm wondering do you think it's most likely these genes that is the root cause for them living so long or could it be something like, I'm just wondering what role mindset comes in.

James Clement:

One of the ways in which supercentenarians live long that we know of is through genetics because that's what we're looking at. Certainly if you look at individuals who are currently supercentenarians and some of the ones that I met over the last 10 to 15 years, you're also going to note that these people were born in the late 1800's, early 1900's. And therefore their diet was also completely different than our diet. Their diets were much more close to what we now consider to be a Mediterranean or Blue Zone diet. So they weren't eating primarily foods out of a grocery store or out of a fast food restaurant. They didn't have the availability of these high energy carbohydrates at their beck and call 24 hours a day. So, even though we can say that their genetics help them overcome the death rate that other people would have been subject to, I still think that their diet did play a role. And that certainly if they had been just incredibly unhealthy and eaten sausages or nitrates and all kinds of terrible things all of their life, they wouldn't have been in the study. And we wouldn't know about them because they would have died along with other people.

James Clement:

So they didn't do anything that was horrifically detrimental or they wouldn't have become the supercentenarians. And in that sense, it's difficult to see who also had the exact same genes that they had. Were diminutive, had low IGF-1 levels, and yet died from something else. Whether it was tuberculosis when they were 30 years old, or influenza when they were 60 or something. We'll never know.

Melanie:

That's such a good point. I guess to do the true supercentenarian study, we would need to get the testing done on every single person ever. Well people at different ages. So we could see, like you just said, the people who had these same genes but did not make it to the-

James Clement:

And I would love to see such a study. Except that unless we learn more about how to hack our own health, we wouldn't be here for the results. But ultimately, that's exactly what you'd want to know.

James Clement:

So for example, there's a lot of factors that show up in studies, longitudinal studies especially. So they'll say that really high levels of protein seem to be harmful to people that are in their forties and fifties. And yet people who are in their eighties and nineties seem to have higher protein intake levels than people in their sixties and seventies. So the question is did they get to that position in life because they had the higher proteins, or are they simply have some sort of mutation where higher proteins didn't kill them off the way it killed off the 45 and 50 year olds?

James Clement:

So when you look across this spectrum, kind of snapshot pictures of what are people eating and what are they dying from in their sixties, seventies, eighties. You're actually looking at, in some regards, totally different human beings. Because when you look at 60 year olds, there's still a lot of people who will only live another 10 years in that group. The median age for men is only 76. The median age for women 82, which means that 50% of them are going to be deceased before that age. So the ones that make it to eighty and nineties and hundreds, are really different. And we haven't been doing this long enough to have longitudinal data where we study the same people from the day they were born, and all the different phases of diets and exercise, and stress, and things like that in their lives until they die. And then correlate all those factors against the people who died earlier. I'd love to have that information, but it would take a lifetime or two to acquire that.

Melanie:

So something sort of similar to that, that I've been thinking a lot about recently. And it definitely relates to your book as well because you do talk about the role of plant based diets and things like that. And I know we see in a lot of 'Blue Zones,' a lot of plant based diets. Something that I wonder just personally having struggled with GI issues and gut microbiome issues. And we're learning more and more about how important the gut microbiome is for health. I often wonder if, okay, looking at the U.S. for example. People who seemingly thrive on maybe entirely plant based diets. Vegetarianism, veganism. I wonder if that almost self-selects for healthy individuals with healthy gut microbiomes, sort of set up to thrive on that diet. Because I think a lot of people, sorry if this is like a tangent. But it's like I think a lot of people with gut issues might actually struggle in that department and following a very, very plant heavy diet for example. So in a way, looking at people who follow a plant based diet for an extended period of time. They might already be at least on the gut microbiome side of things, set up to thrive on that diet. Whereas the people that would experience GI distress and not stick to it might get weeded out at the beginning. It's just a theory that I've been playing around with in my head.

James Clement:

I think you're spot on. I think that's a very astute observation. And I think that the microbiome is really important to health and longevity in general. But I also think that it's a little more flexible than we think. And I follow the work of a number of different scientists that work in this field and do the sequencing of the bacteria in the gut, and follow it. Some of the general observations for years was that it was very stable. Well the other thing that's very stable in most populations is the diet. So if somebody is eating a typical American diet, they'll probably eat a typical American diet for five years or 10 years, or longer. So their microbiome is going to reflect also the fact that they had this particular diet made up of a certain amount of high energy carbohydrates, and proteins, and fats. And whether or not they have fiber will mean whether or not a particular type of bacteria is present or not. Whether they drink dairy or consume cheese, dairy, that sort of thing. Will also determine what kind of bacteria thrive in their microbiome or not.

James Clement:

So I think you can affect your microbiome a great deal by what you consume. And it certainly, if you've got an unhealthy microbiome for various reasons like you killed off a lot of the microbiome because of taking prolonged antibiotics for some reason. Or you got some really bad pathogens that killed off some of your beneficial bacteria. Then it might be really hard to go back to a certain type of diet that you had before. Or if you're trying to adopt a new diet to do that because your population of those bacteria that would process that particular food type is really low. It takes time for this to build up and for these populations to essentially replenish.

James Clement:

One of the things that they see in centenarians and super centenarians is that they have much more diversity of microbiome bacteria than general populations. So it's a little bit conflated by different issues. The fact that where they live and many of them have lived in rural areas, are exposed to more animal bacteria. And they work in their gardens. So this is very true of many of the Blue Zones where people generally have their own gardens. So you're also working in the soil and picking up bacteria more when you do that as well that a lot of us who live in cities wouldn't be really exposed to.

James Clement:

So all of these factors influence how your microbiome is going to relate to the food that you're consuming. And I'm going to use this word a lot in your program, but you can hack this as well. So you can take probiotics. And of course when you make a change of diet, then you need to take into consideration that you need a period of time in order to allow this population of bacteria in your gut to diversify and to support the diet that you have. And there might be various uncomfortable aspects to that. Bloating and gas, and other issues. But over time, that should come back into alignment.

Melanie:

Yeah, I love that so much. And actually speaking to that just really quickly, I know it's kind of complicated. Because on the one hand, we see such almost rapid transient changes in gut bacteria based on dietary changes. But then we wonder at the same time, is it possible that certain species are completely lost and you can't recover them.

Melanie:

But I actually saw a really fascinating study the other day. I'll have to pull it up and put it in the show notes, and I don't remember the specifics. But it was basically looking at some sort of modern day hunter gatherer population. And apparently due to their seasonal eating, they go through periods where they actually completely lose strains that we have lost in our modern world. But those strains actually come back when they start a new dietary approach based on the seasons. So that was actually, I mean that was really encouraging because it's like seemingly, maybe it is possible to make lasting changes.

Melanie:

But another thing that kind of ties into your book is it was very empowering because you do go through all of these lifestyle changes and things we can do for those of us who are not the lucky lottery winners in the genetic lottery. So I'd love to tackle some of the big topics in the book. So for example, one thing. Well of course listeners are going to wonder what is the switch. So we'll get to that.

Melanie:

But one of the big topics in the book that I personally am obsessed with is the concept of autophagy in the body, and how that supports health and longevity. So I was wondering if you could tell listeners a little bit about autophagy. I will say I've read a lot on autophagy, and your book was the first time that I really got a sense of what was going on. It made sense. And you used the analogy of a garbage truck and things like that. I really appreciated the science talking about the actual process and what it looks like. And it was the first time that I could kind of really visualize it in the cell. So for listeners, what is autophagy and why is it important for longevity?

James Clement:

So I think the place to begin with autophagy is the fact that animals and plants evolve from bacteria. And somewhere along the billion years that we only had bacteria in the world, some of them evolved the ability to hunker down when resources weren't always available, and turn on a process inside their cell that allowed them to get some of their nutrients from the cell itself and to shut down processes that weren't absolutely necessary to continue living. And this was in bacteria referred to as TOR, T-O-R. In mammals and other organisms referred to as mTOR stands for mechanistic target of rapamycin. And when autophagy is turned on, it basically is a little membrane that forms. And it selectively, and again, this is an evolutionary process that it's become selective. So it's selectively takes out things like misfolded proteins and dysfunctional organelles, which are inside the cell. And that includes dysfunctional mitochondria. So ones that are fused and not producing high levels of ATP, are producing high levels of free radicals, which are dangerous to the cell.

James Clement:

These kinds of misfolded proteins and dysfunctional organelles are essentially scooped up by this membrane and taken to the lysosome. This is a sort of acidic sack inside the cell where things are digested. And it merges, dumps the contents in it. And those are broken down, and some are recycled inside the cell as amino acids that can be used to make proteins. And other things are just gotten rid of as waste.

James Clement:

So the analogy of a garbage truck going around and picking up litter and taking it to a central recycling center. What I use in the book, and of course in real life in biology, this is an incredibly complicated process that people like Ana Maria Cuervo have spent their lives exploring. And we still don't know all there is to know about this. There are dozens of genes involved in just forming these membranes. And then how are these proteins and organelles selected? How is the membrane moved to the lysosomes? It's all really incredibly fascinating. And people can go down rabbit holes looking at and talking about these processes. But as we'll talk about in a little while, it's incredibly important to our health.

James Clement:

And one of the general reasons to think about this is that why would it be important to our health, is the fact that this was a process that was turned on. It was turned on, on a regular basis in plants and animals, whenever resources were limited. And this is something up until very recently would have been turned on in humans overnight on a regular basis. And then for prolonged periods on a regular basis also, where you had seasonal changes in food availability. Or you have a storm blows in and you're snowed into your cave and you can't go out and gather or hunt. For lots of reasons, humans have had limited availability of resources for most of our history as well. So things like autophagy would have been turned on. It's a natural part of human longevity that exists.

James Clement:

So when you keep it turned off all the time, you really end up with something that I prefer to call accelerated aging. And I believe that most of the diseases that are associated with autophagy being turned off such as diabetes, and heart disease, and cancer, and Alzheimer's, etc. That these are actually problems that are sort of linked mostly now to Western civilization, Western diets. And to a few genetic mutations that some people have that don't allow autophagy to work exactly correctly. Some of these lead to higher risks of cancer, or Alzheimer's for example. But this process is really key to why humans live as long as we do already.

Melanie:

So question about that process. One of the things you speak about is how it is good for clearing out damaged mitochondria, for example. And also, I think a lot of people often think that autophagy is on or off, like it's happening or it's not happening. But there is this idea that there's a baseline state of autophagy occurring all the time. I think you've mentioned how it's more like a dimmer switch than on or off.

Melanie:

For things like, you were just talking about intense health conditions and such, which might be correlated to not having adequate amounts of autophagy. Does that mean that for things like damaged mitochondria or certain health issues, that the body would never address that or clean that up unless we create a state of energy necessity? Is that going to have to happen on some extent, be it through fasting? So not taking in any food, be it through protein restriction. Or will the body still be tackling that with autophagy? Do you think it requires some sort of lifestyle intervention to get it to happen?

James Clement:

I think that it takes for people living in the west especially, it takes a lifestyle intervention in order to restore autophagy to what it would have been like had we lived hundreds of years ago rather than now. And I talk about this in the book, the industrialization, the changes. And these are all great things. It's wonderful that now nutrition isn't as big a problem as it was in human history. That we have fewer and fewer people dying of malnutrition.

James Clement:

But on the other hand, the fact that we have goods flown in from all over the world, available to almost anyone at any time, regardless of the season. That we have lots of companies that take products that we would have eaten only a little bit of and made hundreds and hundreds of products from those. Things like grains for example, and then made them all available in one place like a grocery store where you can go down entire aisles that have literally 1,000 different products all made from one particular grain. That's new to human history. And very much through methods that we'll talk about later, cause autophagy not to be turned on and essentially hold the brake on autophagy so that it's at a very, very low level. And I think this is what's leading to these so-called diseases of civilization that I talk about. And it does need to be remedied. In other words, we need to get back through practices of either time restricted eating, fasting, a ketogenic diet, etc. So that we turn on autophagy on a more regular, natural basis.

Melanie:

And then a followup to that, what you just said. How do you feel about the autophagy potential for those different approaches? So for example, do you think somebody could get a shallower or deeper sort of autophagy from something, for example like intermittent fasting but then eating a surplus of calories in the eating window compared to maybe a ketogenic diet but you're eating constantly? Compared to maybe just eating constantly, but calorie restriction. Compared to maybe not calorie restriction but protein restriction. So there are a lot of different types of 'restriction' that might, is one approach going to create a more effective, therapeutic autophagy than another type. Or is it just based on the individual? What are your thoughts on that?

James Clement:

I think that's a great question. So this switch, we've alluded to it before. mTOR is sort of what determines ultimately whether the cell is in an anabolic state, where it's growing. It's making proteins by growing, I mean the cell is reproducing, etc. This as opposed to it's in kind of a hunker down state, the catabolic state where autophagy is upregulated. And it's clearing out these misfolded proteins and mitochondria, etc. Then this is something that you see in these populations that I talk about. So I sort of singled out three examples of populations that have been studied for maybe three decades or more. So these are long term essentially clinical trials if you will in the sense that large groups of people have chosen to follow a particular lifestyle. Or because of where they live, they follow a particular lifestyle. Or a religion, they follow a particular lifestyle. And this has caused their mTOR autophagy switch to be more in balance with what I've been describing. And this is the Okinawans, the Loma Linda vegans, and the Mount Athos monks as three examples.

James Clement:

And what you find is that in these groups, they have a much greater reduction in the risk of these diseases of civilization. Diabetes, cancer, heart disease, etc., than the general population, and tend to live longer. So that's sort of the equivalent of a large clinical trial. And I give these as examples because if you trace this back to what's going on inside the cell and whether or not autophagy is turned up or turned down, this kind of answers what some particular lifestyles can do.

James Clement:

So this is really good evidence for people that want to know what's one of the better proven ways that I can have a greater chance of living to 90 or 100 without heart disease, and cancer, and Alzheimer's. Well certainly looking at the Mount Athos monks, the Okinawans, and the Loma Linda vegans is a way of reducing your risk. Because this is what they have, and this is how it relates to this switch.

James Clement:

But you could lead a completely different lifestyle, and you could hack your biology with drugs and supplements. And occasionally going on a prolonged fast. And also turn on autophagy. It's just that, and I talk about this in the book. But what I want to point out is that there aren't large scale groups of people that have been doing this for 30 years or more that we can point to and say, "Yes, you can be a total carnivore or a ketogenic diet person. And you will have reduced risk of disease." The molecular biology tells us that there are ways to do those diets and to do them such that you turn on autophagy from time to time, and that you could make it into a healthy diet. But you don't have this evidence that already exists that eating mostly vegetables and very low amounts of meat, primarily branch chain amino acids. Those things are what will give you the greatest health benefits. We've got lots of data that show that.

Melanie:

Yeah, I think it's complicated. Because I feel like we do, like you just said, we have all this data on these other approaches. Like you said, the fruits, the vegetables, the limiting the protein, things like that. And now we have this whole new movement in a way of people trying things like carnivore. Or I feel like even more recently since intermittent fasting has become much more popular as a lifestyle, people are playing with that while not necessarily addressing what they're eating in the time restricted eating patterns. So there's more doubt on that definitely than carnivores. But I guess what I'm thinking is that it's hard to know what the implications are of things. Like for example, I keep using the carnivore diet as an example. And I think it also kind of convolutes the whole protein idea because ... I'd love to go in deeper into the mTOR and the role of protein and amino acids and things like that. Because I'm so fascinated by it.

Melanie:

Because on the one hand like you said, we do have a lot of these studies and we see things where lower protein intakes or certain amino acids correlate to longevity. But on the flip side, have we seen studies or things where people are following higher protein diets and fasting patterns or maybe higher protein, lower fat diets and how that affects longevity? So what are your thoughts on protein and longevity? I thrive on a high protein diet. So I'm just wondering more about that.

James Clement:

I'm going to go back to one of your original discussion points. And that's about the complexity. So in the book, I did create a food pyramid. And I did say one of the simplest things to do is just choose one of these lifestyle patterns. Start eating like an Okinawan. So when I say that, I don't mean you have to eat sashimi and Asian vegetables, etc. What I mean is that one of their main lifestyle choices is that they supposedly only eat to 80% satiety. So they always go away from the table a little bit hungry. That's a custom. And it's considered rude to go to somebody else's house and sort of eat until you're full. And they also eat very little meat. Their meat's primarily used as like a condiment. So it works out to something like four ounces a week.

James Clement:

I've had people write to me and say, "I'm trying to cut back on protein and I want to have two, four, or six ounce pieces of meat a day. And that'll be about half of what I was normally eating." And I say that's an improvement then, but it's not optimal. And these groups that we study are sort of what we have to at least use as a guide at the moment in terms of they appear to be turning this switch, mTOR switch down and an autophagy up by following their low animal protein diets. But that doesn't mean that's the only way to make it work.

James Clement:

And one of the things I love about specific diets. Whether it's paleo, carnivore, veganism, etc. Is that for many people, it's an elimination diet. So if you're following an American, a typical American diet. And I read one study that just sort of made me gasp. Because the study was about protein intake, but it showed the nutrient breakdown of all the foods that this fairly large group of people consumed. So it had high protein intake, medium protein, and low protein intake. And the high protein were the biggest meat eaters. But because the study was focused on that, they didn't really go into other aspects of it. So when I was looking at the data, what shocked me was the people who had the most amount of protein from animals also had the highest caloric intake and the highest amount of calories from carbs compared to the people that followed other diets. So really it was kind of a gourmand, over consumption of food in general. So they had higher protein levels, but they also had higher carbohydrate levels if you were looking at that or higher fat levels, if you were looking at that. And health-wise, the combination of high fat and high carbohydrates is basically-

Melanie:

The worst.

James Clement:

Absolutely. It's basically what scientists give to mice to cause them to become diabetic so they can study diabetes, or to get fatty liver disease so they can study nonalcoholic fatty liver. So it's sort of like the worst of all worlds. And personally, I had this sort of a diet for maybe 10, 15 years of my life when I was a practicing law in Honolulu. I sought out a really good health practitioner on my side. And this is around 1982. And I found Dr. McDougall. Who was still primarily a specialist in breast cancer therapy at Queens Hospital. And he had talked me into, I was convinced by his work to become a vegetarian. But this is years before the glycemic index became popularized. So I was consuming tons of bread, and bagels, and pasta, and rice, with loads of cheese. Because I also wanted to get fat and protein in. And it really ended up wrecking my health. So it really took learning about the glycemic index and its effect on blood sugar. Which of course is one of the main elements that trigger whether the switch is in the anabolic or catabolic state. That allowed me to sort of get back on top of my personal health.

James Clement:

You were asking about the switch a little bit more. I think maybe this is a good time to talk about how it works. So there's this upstream set of environmental sensors. So inside the cell, there are receptors that basically tell the cell whether you have enough glucose for energy making, whether you have enough growth hormone. Whether you have enough oxygen in certain types of proteins. And all of these channel through upstream genes and protein complexes that then send signals to mTOR as to whether it should be in the anabolic state or the catabolic state. And one of these big ones is called AMPK. So there's a lot of things that can essentially flip this switch at the AMPK level and have it put the brakes on mTOR.

James Clement:

And what I was sort of astonished with when I had done this research initially back in 2013 was that almost every life extending therapy. Whether it was fasting, calorie restriction, protein restriction, including methionine restriction in rodents. All of these things basically affected the mTOR status, whether it was in anabolic or catabolic. And many of the life extending drugs that we knew of from Metformin and rapamycin. But lots of supplements and things. So ECGC, even simple aspirin. All of these things tended to upregulate autophagy by putting the brakes on the mTOR. And for awhile, I was suspicious that absolutely everything we knew always ended up in this one complex mTOR. And that it only affected this condition of whether or not we were in autophagy or not. Luckily that's not the case and there's plenty of anti-aging things that we've learned that are outside of this one particular complex. But there's also a question of whether or not these things, and this was sort of my initial question in doing this research in the first place back in 2013. Whether intermittent fasting, and calorie restriction, and protein restriction overlapped. Or whether they would be additive if you did them all.

James Clement:

So could you restrict your calories to say 80%, also do intermittent fasting from time to time, and limit your protein intake? And would you have multiple effects from that? Or would they sort of cancel each other out? And it turns out that they mostly cancel each other out, because they're working on the exact same pathway. So if you've properly put the brake on mTOR by getting lower glycogen stores and turning off that particular sensory switch so that mTOR is inhibited. Then autophagy gets upregulated. And cutting proteins at the same time won't really greatly increase that. You may increase it a slight amount, but they're not additive as other kinds of therapies can be additive when you put them together.

Melanie:

So to clarify, when you say cancel each other out, it's not that they make it worse. It's just there's not an additive effect necessarily?

James Clement:

Absolutely. That's what I mean by, the fact that you've already put the brake on doesn't mean if you put another foot on the same brake and press the same amount, that it's going to be additive. So it's really the fact that they all work on the same pathway primarily. And that the greatest benefit is in turning autophagy on.

Melanie:

So another question to that. Intermittent fasting specifically, a lot of times people make the argument or posit the idea that the benefits of intermittent fasting are solely due to either calorie restriction or weight loss benefits from it. That the fasting itself is not any different, especially compared to calorie restriction. That there's no superior benefit to intermittent fasting. Do you think the effects of intermittent fasting are due to perhaps intentional or unintentional calorie restriction, or do you think that there are different pathways being activated with that?

James Clement:

I do believe that it's primarily the same pathway. But you can't just get the same effects from calorie restriction. I think that's more of the longterm, overnight effects of small amounts of autophagy. Because your glycogen stores and your protein levels are slightly lower to begin with. And therefore as you fast overnight, autophagy is going to be slightly more elevated than otherwise. Than if you ate 100% of the calories that you would want to take in.

James Clement:

Whereas with fasting, you're really knocking out the glycogen stores, the lowering the insulin levels, and reducing the branch chain amino acids that are coming to the cell. So it's a much more direct and important way of blocking mTOR, inhibiting it, and increasing autophagy. And I think that prolonged fast, you get deeper levels of autophagy. So there's actually four or five different types of autophagy in biological terms from macro autophagy is basically what everyone calls autophagy. But there's mitophagy, which is taking out the mitochondria. There's xenophagy, which basically takes out foreign cells. Bacteria, viruses, things like that, that are inside the cell. And chaperone mediated autophagy, etc. So there's lots of levels of autophagy. And I think that this also gets activated in the longer term fast, where people fast for let's say 72 hours or more. So you get a little bit different effects from these prolonged fasts than you would from just the normal overnight fast.

James Clement:

But that doesn't mean that you have to do this. It's just in a sense more is better. To the extent that you're doing overnight fasting. And then occasionally, you're able to also do these more prolonged fasts. So the fact that they are the same pathway doesn't necessarily mean that instead of fasting for three days, you're just going to cut your calories by 20% for three days. You won't get the same effect as the fast. Does that make sense?

Melanie:

Yeah. Yeah it does. And to that point, because a minute ago we were talking about how there doesn't seem to be an additive effect to combining protein restriction, calorie restriction, fasting. That the benefits might plateau. But might that be a case where combining would lead to greater benefits? Because for something for example like a fasting mimicking diet. Because then maybe it's allowing you to almost get the effects of a longer fast by very specifically combining these different things like the extremely low calorie intake with the fasting, with likely the protein restriction as well?

James Clement:

So the prolonged diet of Valter Longo and some that I've seen from other researchers, where you cut your calories to somewhere between six and 900. And you're greatly reducing the protein level especially. And there's no animal proteins that are allowed during that time period. These are triggering the same sensors that will break mTOR and put on the brakes and to upregulate autophagy as fasting itself. And it sort of depends on your state and how often you do this. So if you have fairly full glycogen stores and then you supply your body with just enough carbohydrates that it doesn't completely exhaust the glycogen stores in the liver and the muscles. Then autophagy is not really going to be upregulated to the extent that you would desire. You really need to exhaust those glycogen stores, which will reduce the insulin levels and cause this braking effect on on mTOR.

Melanie:

Okay, got you. Another question while we are still talking about calorie restriction. Something that was fascinating that you discussed in the book that I was not aware of was you talked about how some of the potential negative effects of calorie restriction could be abolished when calorie restriction was paired with exercise. Which I found very, very fascinating. What do you think might be going on there?

James Clement:

Exercise and calorie restriction work really well together to reduce the amount of available energy that your cell has, and to turn down mTOR and to turn up autophagy. It's not something that I would say the detrimental effects of calorie restriction are remedied by exercise. I would say that exercise is an enhancement to calorie restriction. And to some extent, to intermittent fasting.

James Clement:

Some people have a hard time keeping their blood sugar from really getting too low when they fast. And I know this is especially true of particular gene types. So in that case, you probably wouldn't want to go to the gym and try and do a major amount of heavy stressful exercise or running on a treadmill for hours. You might get your blood sugar a little too low. But in general, it's a great way to reduce ATP. And this is one of those sensor inside AMPK that basically turns up autophagy. So I would definitely be in favor of adding exercise to your regimen in order to enhance your autophagy levels.

Melanie:

The part in the book that I was referencing was that adding the exercise protected bone muscle and aerobic capacity compared to not having the exercise. So I wonder if that is part of it. Because people, especially with intermittent fasting for example, often worry that they will lose muscle mass by fasting. When really it seems that during the fasted state, growth hormone is actually upregulated and actually can provide a stimulus for muscle growth upon refeeding. So I'm just so fascinated by all of it and how things that you think might be contrary to what you want are actually the opposite. It seems to me like the body, if it's being told that it needs to, and maybe this is putting things too casually. But if it's being told that it needs to maintain these systems, so bone, muscle health by things like physical activity, then it's in my opinion, it seems like it's going to work to maintain that. I'm just fascinated by all of it.

James Clement:

There's certainly a plethora of studies that have shown that exercise is immensely beneficial at any age, and that it has lots of beneficial qualities on reducing sarcopenia, the loss of muscle as you age. Of keeping your bone density high and not getting osteopenia. So I would certainly encourage people to exercise at all points of their life.

James Clement:

So one of the things I talk a lot about in the book, and I try to make a very specific point about was that you can't say intermittent fasting sounds really beneficial. So I'm going to do it everyday for the rest of my life. That's not how we evolved either. We need mTOR. mTOR tells the cell to multiply and to make proteins. And we want muscle cells to multiply. We want STEM cells, chondrocytes for our cartilage and cardiomyocytes for our heart. Satellite cells for our muscles. We want cells to proliferate at times. We just don't want to be locked into a lifestyle and dietary habit where cell proliferation is all we do. Because cancer is also a form of cell proliferation. So if you have cancer cells in your body and you're keeping mTOR going because you've got the accelerator pressed down and never put on the brake, this can lead to higher risks of cancer. But we definitely need mTOR, and we need to have this refeeding period.

James Clement:

So it's a combination of we need to balance, the switch being off and the switch being on so to speak. So upregulating mTOR part of the time and then downregulating it or inhibiting it other parts of the time. And this sort of cycle which I get into as protein cycling. Because protein is one of the main switches that you can use to manipulate mTOR. This is sort of the way we evolved and the way that is going to help you avoid all of these diseases of civilization.

Melanie:

That was actually something I had a huge question about. Because in your book, you do talk about this cycling. And you put forth this idea in the end that perhaps we can live this lifestyle where we have about eight months or so that are high autophagy months. Almost like AMPK months. And then four months that are anabolic. So more on the mTOR side of things. How do you think that compares? So that approach of a monthly type cycle. To something, I mean I know you just mentioned the idea of not doing intermittent fasting every day for the rest of your life. But what about comparing that? A fluctuating seasonal cycle, compared to what if somebody had that same fluctuation but on a daily basis? So they're doing daily intermittent fasting, but consuming for example a high protein meal in their eating window. So they're stimulating mTOR every day, but they're also doing the fasted state every day. Do you think that those two approaches are vastly different, creating different effects? I'm just wondering what your thoughts are on that.

James Clement:

I do think those are two completely different approaches. I think it's very hard to regulate this and get the desired results by just trying to squeeze, turning off and turning on autophagy in a single day, and to do that repeatedly. And part of the reason is we know that it takes six to 12 hours for many genes to switch over from one state to another. So even when you've depleted your glycogen for example, and your mTOR sends out this signal or AMPK sends out a signal to mTOR saying, "Let's go into this catabolic state." It still takes a period of time for all these various sirtuin and FOXO, and other genes that then tell the cell, "Let's start consuming fat because we don't have enough glucose in the bloodstream."

James Clement:

You go through literally thousands of gene changes, and this doesn't happen rapidly enough to say that you're going to get the full benefit of autophagy only at night. And that every day you're going to wake up and you're going to have a big shake for breakfast so that you can turn back on mTOR. We really have to go through feeding and fasting periods on a much more prolonged basis to get the optimal effects of autophagy.

James Clement:

So one thing is sort of just being more natural. And the more natural is to follow these lifestyles that I talk about in the book. Which are related more or less to kind of an older practice of living closer to the land of having vegetables and less meat. And all the things that humans sort of evolved to consume up until very recently. Had limited resources, etc.

James Clement:

But the other part of that is the idea that you can optimize this for even greater health and longevity by intentionally turning on autophagy for periods of two or three days at a time. And there's hundreds of studies that have been done showing that intermittent fasting has incredible benefits. Neurological reducing heart disease and cancer. On and on and on.

James Clement:

And it goes back in recorded history to even the ancient Greeks. They prescribed fasting for numerous ailments. And you see this in almost every religion, that they included fasting. And it's probably not a coincidence. Meaning that it was found that these things were beneficial, and so they were codified into things that people should do. And there's many religions like the Eastern Orthodox religion, which has sort of a longterm fasting built into their religious calendar of the Mount Athos monks fast something like 180 days of the year. But most of those fasts are sort of the Valter Longo, prolonged sort of style of reduced calories. So they're only allowed to eat for five minutes in the morning, and they're not allowed meet during those days, during their fasting days. And they don't normally have dairy anyway, just because the monasteries don't allow women or females. And that includes everything except cats. So they don't have cows or goats that give milk. It's a long involved story as to how that happened or came about. They do have female cats, but they're not allowed to have female livestock. So they don't have dairy. And then they limit meat to only feast days. So these kind of lifestyle practices show us more optimal ways and how these prolonged fasts can be incorporated into your lifestyle, and the kind of benefits that you would get from that.

Melanie:

Okay. Something that you brought up that now I have a question I'm dying to know the answer to. So you're mentioning that it takes around six to 12 hours for these genetic changes to happen. So is that one of the reasons that people might experience certain things around the same time of days because that's how long it takes for these gene changes to happen? Or becoming hungry at a certain time or becoming, I don't know, even more energetic at a certain time? Does that all relate to that's how long it takes for genes to switch on and off, or would that be more other things?

James Clement:

I think what people typically refer to as carbohydrate craving. Or they just say, "I tried to do a fast or I tried to do ketogenic diet." Both of which are are low carb. One of the things a lot of people say is that I felt all my energy was gone, and I just craved food. I just couldn't help it. I had to stop and get something to eat.

James Clement:

I think that's tied in to the fact that if you've never fasted or you've never sort of deprived yourself of calories for a period of time, then your cell has gotten used to the fact that anytime blood sugar is low, you're going to fix that for them. So the cell just sort of chooses to lower the metabolism until that new glucose comes to it because that's what works every time.

James Clement:

So the cell will actually match, metabolically match the amount of energy that you're providing to it. But if you retrain those styles to consume fat when the glucose levels go low, and you can do this with the ketogenic diet or with prolonged fasts. Then your cells will go back to being able to readily switch to burning fat instead of sugar. And when that happens, almost everyone that I've personally talked to about doing fasting, especially who have had this problem, I've said, "Well instead of switching immediately to a fast, why don't you do a ketogenic diet and slowly cut down your carbs until you know you're at like net 20 grams of carbs a day?" By net we mean that you subtract the fiber, grams of fiber from the grams of carbohydrates. So for a lot of foods like low-glycemic foods like broccoli, and cauliflower, and asparagus, and spinach and things like that, you can basically eat all you want or all you could hold. And you still won't break the 20 grams of net carbs.

James Clement:

But by doing this and training your body, so you're still consuming lots of calories. But they're in the form of primarily fats, and you want to do healthy fats if possible. But by training your body to burn fats again, then when you want to do a fast, you don't really get that complaint. You don't get the cravings, and you don't get this sort of resulting dopamine and serotonin deprivation that you would otherwise get. Because as you probably know, about 95% of the dopamine and serotonin in your body comes from your gut. And in a sense, lots of those gut bacteria are simply rewarding you for feeding them what they want. And when you primarily eat carbohydrates, then your gut bacteria become overpopulated with these particular bacterium. And when they get what they want, they reward you. And when they don't get what they want, they essentially get stingy and don't reward you with the dopamine and serotonin.

James Clement:

So this is sort of why you see people going to the same types of high energy foods whenever they search for something which they would refer to as a comfort food. Is this is because they're basically giving something to their gut bacteria that's going to allow the gut bacteria to release serotonin and dopamine.

James Clement:

So I think you can again, hack all of these systems by training your cells to burn fat and to getting out of this process where your body rewards you every time you eat a carbohydrate. And you get really cranky, and headaches, and you have other problems when you try to wean yourself off of it.

Melanie:

Yeah, that's something I often think about is this idea that we know our brains love ... we talked about the gut microbiome, but our brains love habits and love patterns and things like that. And I've read doesn't really care in a way what they are. It just likes this idea of these habits and these routines. So when it comes to diet, I'm like why not? Especially given that and then given what you just spoke about, about how our gut microbiome might be craving certain foods. It's like why not experiment to find the diet that works for you on a health side of things? Because ultimately, you can definitely derive the same amount of pleasure from that diet once you kind of like you said, stick it out and get to that point where you're deriving the same amount of dopamine and serotonin from it.

Melanie:

I did have one more quick question. You were talking about the genes being activated and AMPK. It's often posited that certain compounds encourage autophagy like black coffee for example. Or there are these AMPK activators supplements, things like resveratrol, quercetin, other things.

Melanie:

But now I'm wondering, because if you're talking about takes substantial amount of hours for those effects to happen. Does that mean having black coffee while fasting for example, is not really upregulating more autophagy at that moment? Or for example, I have a supplement that's a 'AMPK activator' and it has compounds that are supposed to jumpstart AMPK. Is it possible to jumpstart it quickly, or is it not? Does it require longer?

James Clement:

It is possible to jumpstart the switch. Say I have decided that you're going to calorie restrict or to fast. Then you still have glycogen stores that you're going to have to burn through. And the average 150 pound person has somewhere between 800 and 1,000 plus calories that are stored in their liver and muscle tissue. This is related to basically our fight and flight ability. So we want to have high energy resources available to the body, because you never know when there's going to be a saber-tooth tiger leap out of the bush, or at least this would have been historically accurate. Now you wouldn't know when your boss is going to say jump up and do something for me kind of thing, and you get all stressed out. So your buddy likes to store this high energy glucose in the muscles, in the liver, and to have it available for kind of stressful things. We store most of our energy for 150 pound person, it's like 135,000 calories. So something like two months worth of energy needs in the form of fat in the body.

James Clement:

So these two different methods of how the body stores energy means that you can burn through the glycogen stores and still have plenty of energy for the body to operate. But because now your insulin levels are going to be low and that's how the cell determines whether or not there's enough glucose and energy to power it, to keep mTOR turned off and to make proteins and to reproduce, etc. Then that's the way that you can turn these switches in your favor. So taking an AMP activator is a way of sort of well I don't have to wait six hours for my glycogen stores to burn up naturally because I've stopped consuming. I can sort of preempt that and start them now by taking in a various compounds.

James Clement:

And I think I had a list of maybe 31 different compounds that all activate AMPK and put the brake on mTOR. And there are certainly numerous drugs to do so as well. Metformin and rapamycin come to mind. So it's a way of both reinforcing autophagy and turning it up maybe to a little higher level. And also a way of starting it earlier than it might start if you were just going to wait till all of your glycogen levels were low enough that your insulin levels lowered and your IGF-1 levels lowered, etc.

Melanie:

I'm glad you said that because I've really been benefiting, I feel like from my AMPK activating supplement, so sounds like it's okay to keep using that. Here's a huge question I have that haunts me. It really does haunt me. People will look at things like the ketogenic diet or something like gluconeogenesis in the liver. And say that these states are basically emergency states, that they're not the natural state that the body is designed to be in. And because of that they are 'stressful' on the body. Do you think they are 'stressful' on the body with negative ramifications from that? Does the body even think in that sort of terminology? I mean I think about this a lot with gluconeogenesis and producing glucose from protein substrates for example. And that's often said to not be the natural state of things. So does the liver, not that the liver is conscious, but is it stressed out by the idea of doing gluconeogenesis compared to deriving energy directly from say glucose for example? Do you have thoughts on that?

James Clement:

Sure. Let me kind of break this question again into parts. So the gluconeogenesis just in and of itself. One thing that really turns this on is stress. So elevated levels of cortisol will basically put your body in this fight or flight mode. For many people, this happens around the clock. It may happen because of their work environment, or just their personal lifestyle. And your body prepares for this fight or flight by breaking down some of the proteins, primarily in muscle cells. And making glucose from that. So you can get a little gluconeogenesis when you go into a fast or when you do calorie restriction. But the main source of this process is actually stress.

James Clement:

I had a really interesting self-experimentation where I needed to cut down some really large trees that were next to this laboratory I was building here in Gainesville. And these are really massive trees. So if they fell in the wrong direction, they could take out my entire building. So I did this repeatedly. And as part of my normal self-quantification process, I've been taking my blood sugar multiple times a day for about six or seven years now. And keeping this in a diary. I actually use Google Calendar for this purpose along with what I eat and that sort of thing so I can sort of look back and see how different foods affected my fasting glucose the next day and how different activities during the day might change my glucose. And one of the things that immediately I discovered was that I could have fasting glucose in the morning of let's say 87. Not have any breakfast, and then go out and work on cutting down.

James Clement:

So chainsawing a large dead tree that was close to my lab building that I was really stressed out about if it went the wrong way. And come inside and take my blood glucose, and it would be 150. And that increase in blood sugar was all due to cortisol basically reading my emotions and the stress level and saying, "Oh my God, something really bad is about to happen. And James may need to run like heck." And basically just producing copious amounts of blood sugar, getting ready for whatever this emergency was going to be.

James Clement:

So I don't know if you've come across this before, but DHEA is sort of the yin to cortisol's yang. And you can reduce the levels of cortisol by increasing your levels of DHEA. So I went out another day and wanted to see what happened when I took a big dose of DHEA in the morning before I went and did this. And as it turned out, it was only a very small increase in blood sugar. So it really dampened this fight or flight response. And all the attendant neoglucogenesis, etc., that you get from elevated cortisol levels. And I even did this repeatedly several days in a row just to see if I was observing something real, or if this was just anecdotally, it happened once. But the next day my cortisol levels weren't high, my glucose levels weren't high, etc.

James Clement:

So how this ties into society and life and everything is that a lot of people have very stressful jobs. I was a Park Avenue lawyer for awhile, and I can tell you that I bet my cortisol levels were elevated 12 hours a day, six or seven days of the week. So you're producing glucose because of this, and you're constantly keeping elevated blood sugar levels. Even if you're trying to keep a low carb diet. And I tell people in those kinds of situations to try and find ways to destress, to either change jobs or take up meditation. Or I became a marathon runner, which really helped with my stress levels. So I think the neoglucogenesis more important in this aspect than it is in terms of the little effect it's going to have on autophagy or how it might sabotage autophagy.

Melanie:

Yeah, that is so fascinating. And it really resonates with me because I know just looking back at my lifestyle at my life and the different dietary approaches I've tried. I was super low carb for quite awhile, but I always had high blood sugar levels. And it actually wasn't until I switched over to actually a high protein, high fruit diet with intermittent fasting. And my blood sugar levels got great from that. And I think it's the whole, for some people their body might not enter that stress state on a low carb diet. But for others, they might perhaps need higher carbs or other changes to not have that cortisol response.

Melanie:

Do you think if somebody does have high blood sugar levels, despite not taking in, let's say somebody is doing, they're taking in no carbs, but they have elevated blood sugar levels. Do those blood sugar levels have the same potential for negative health effects as somebody who has high blood sugar levels from taking in sugar? Or is it worse in one case or the other?

James Clement:

Great question. So elevated blood sugar primarily causes two things that are very relevant to aging and our susceptibility to disease. So one is that they basically fulfill one of the necessities of keeping mTOR on. So in other words, you're not going to be breaking mTOR because you've got low blood sugar levels.

James Clement:

The other important thing that I talk about in the book is that AGE, so advanced glycation end products. So the glycation part of that is specifically glucose. And how this acts is basically glycation is a process of these sugar molecules binding with proteins and sort of gumming up the works if you will. So if you're familiar with the crème brulee, you basically sprinkle sugar crystals on top of something, apply heat. And it makes a glass like surface to a custard. And that is a glycation effect. And that same thing happens to the inside of your blood cell, blood vessels.

James Clement:

So those proteins that are exposed to the bloodstream and exposed to these high levels of glucose become glycated. They become brittle. The proteins are also harder to function in the ways that they are meant to function. And all of this increases the risks for hardening of the arteries and atherosclerosis. So it's not beneficial for your health at all. And it doesn't really matter how the glucose got into the bloodstream. The fact that your proteins are exposed to it for long periods of time is what causes this glycation, advanced glycation end products. And causes these detrimental effects.

Melanie:

Wow. You've just answered the question that I've been wondering for so long. Yeah. Because I was wondering specifically with AGEs, I was wondering did it matter if somebody had high blood sugar levels despite not taking in seemingly carbs? Was there still a potential for something like that? So that's really fascinating. Thank you.

Melanie:

There is two more topics I'd love to touch on briefly if we have time. One is the role of antioxidants in the diet. And I loved everything that you talked about that in the book. And also a question that's been haunting me is the idea of endogenous versus exogenous antioxidants, and the potential benefits and even potential downsides to at least exogenous antioxidants. What are your thoughts on the role of exogenous antioxidants in the body? Do you think that everybody could benefit from them, or is there the potential that taking in too many antioxidants say from food might downregulate our natural production of antioxidants? What do you think is the best approach to that? And then of course, there's the whole people of the carnivore movement will say that they're the ideal form of antioxidants because they're just producing them endogenously. So what are your thoughts on antioxidants?

James Clement:

Well, we're only alive because we have endogenous antioxidants right now. So your audience is pretty sophisticated, but I'm just going to go over this very briefly. There's some interesting facts that I think not everyone's exposed to. And it's certainly important to aging and healthy aging.

James Clement:

So approximately 300 million ionizing radiation particles pass through your body every day. 300 million. So this is background radiation from the sun, from the environment, etc. Not manmade. And of that, it creates ten sextillion. So that's 10 with 22 zeros after it, free radicals in your body every day. And this causes 250 single stranded DNA breaks in your nuclear genome of every cell of your body, every day. And about 10 double-stranded breaks, which are so called the worst DNA breaks because it's much more difficult to repair.

James Clement:

Now your cells have lots of repair mechanisms to deal with this. So I could talk at length about the repair mechanisms because it's one of the studies that I've been working on for a number of years involving NAD. And how as a coenzyme with sirtuins and PARPs, it allows for the identification and repair of these breaks.

James Clement: