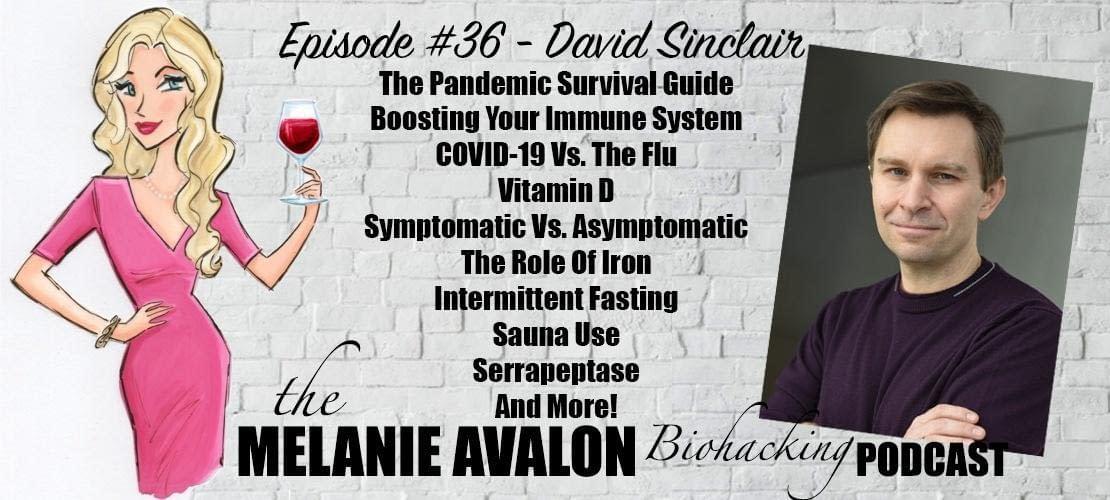

The Melanie Avalon Podcast Episode #36 - David Sinclair

Dr. David Sinclair is a professor in the Department of Genetics and co-director of the Paul F. Glenn Center for the Biology of Aging at Harvard Medical School, where he and his colleagues study longevity, aging and how to slow its effects. More specifically, their focus is on studying sirtuins—protein-modifying enzymes that respond to changing NAD+ levels and to caloric restriction—as well as metabolism, neurodegeneration, cancer, cellular reprogramming, and more.

David is the co-creator and co-chief editor of the journal Aging, has co-founded several biotechnology companies, and is an inventor on 35 patents. Among the honors and awards he’s received are his inclusion in Time Magazine’s list of the “100 Most Influential People in the World” and Time's “Top 50 in Healthcare”.

In addition, David is the author of the new book, Lifespan: Why We Age — and Why We Don’t Have To.

LEARN MORE AT:

http://instagram.com/davidsinclairphd

https://twitter.com/davidasinclair

SHOWNOTES

1:40 - Get David Sinclair's Email Newsletter: The Lifespan Insider

2:00 - Paleo OMAD Biohackers: Intermittent Fasting + Real Foods + Life: Join Melanie's Facebook Group To Discuss And Learn About All Things Biohacking! All Conversations Welcome!

2:20 - LetsGetChecked: Get 30% Off At Home Tests For Iron, Vitamin D, Covid, And More, With The Code MelanieAvalon30

4:00 - Sunlighten Infrared Saunas: Get $200 Off Sunlighten.com Saunas And $99 Shipping (Regularly $599!) With The Code MelanieAvalon

5:45 - Quicksilver Scientific: Go To MelanieAvalon.Com/Quicksilver For 10% Off Quicksilver Scientific Products! Mentioned Supplements: NAD+ Gold (NMN), Liposomal Glutathione, Liposomal Vitamin C

10:00 - Did David Sinclair See This Coming?

12:30 - Viral Vs. Bacterial Infections

14:45 - Are viruses Alive? DNA vs RNA

17:45 - Symptomatic Vs Asymptomatic People

20:00 - COVID-19 And ACE-2 Receptors

20:25 - Age, The Immune System, And The Cytokine Storm

23:30 - TH1 Vs TH2 Dominance And The Implications Of Getting Sick

26:45 - Loss of Information In the Immune System

29:00 - The Origin of COVID-19 And Bat Vs Human Immune Systems

32:00 - Can We Down-regulate ACE-2 Receptors?

33:00 - Should You Change your Medications?

33:20 - The Role Of Vitamin D In Immunity

Melanie's Recommended Vitamin D Supplement: Thorne Research - Vitamin D/K2 Liquid

Get 30% Off LetsGetChecked's At Home Vitamin D Test, With The Code MelanieAvalon30

35:45 - The Role Of Iron and Red Blood Cells In COVID-19

David's Twitter Regarding Iron

COVID-19 had us all fooled, but now we might have finally found its secret

39:00 - The Importance of Exercise

40:15 - BEAUTY COUNTER: Non-Toxic Beauty Products Tested For Heavy Metals, Which Support Skin Health And Look Amazing! Shop At Beautycounter.Com/MelanieAvalon For Something Magical! For Exclusive Offers And Discounts, And More On The Science Of Skincare, Get On Melanie's Private Beauty Counter Email List At MelanieAvalon.Com/CleanBeauty!

42:25 - INSIDE TRACKER: Go To InsideTracker.com and Use The Coupon Code MELANIE30 For 30% Off All Tests Sitewide!

45:35 - Fasting During COVID-19

Why infection-induced anorexia? The case for enhanced apoptosis of infected cells

Infection-induced anorexia: active host defence strategy.

Get 30% Off LetsGetChecked's At Home Diabetes HBA1c Test, With The Code MelanieAvalon30

49:35 - COVID-19 And Blood Sugar Regulation

51:00 - Who Will Get COVID-19? The R Nought, Herd Immunity, And Vaccine Status

52:45 - Have People Already Had It? :The Case Fatality Rate

53:50 - How Does COVID-19 Compare To The Flu?

54:45 - Hospital System Collapse: The Achilles Heel Of Lungs

57:00 - PREP DISH: Get A Free Gluten-Free, Pantry And Freezer Ready Meal At PrepDish.Com/Pantry, As Well As Two Weeks Of Gluten-Free, Paleo And/Or Keto-Friendly Grocery And Recipe Lists And PrepDish.Com/MelanieAvalon

58:30 - If We All Stayed Home... What Would Happen?

1:00:45 - What Impact Does Social Isolation Play In Recovery?

1:03:40 - Should You Take Serrapeptase?

Melanie's Recommended Serrapeptase Brands

1:06:40 - What Supplements Should You Take For Immunity?

Quicksilver Scientific: Go To MelanieAvalon.Com/Quicksilver For 10% Off Quicksilver Scientific Products! Mentioned Supplements: NAD+ Gold (NMN), Liposomal Glutathione, Liposomal Vitamin C

Melanie's Recommended Quercetin: Thorne Research - Quercetin Phytosome

1:08:30 - Sauna And Heat For Viral Infections

(David recommends temperatures above 60 degrees Celsius, 140 degrees Fahrenheit)

1:10:00 - Is COVID-19 The Catalyst We Need?

TRANSCRIPT

Melanie Avalon:

Hi, friends. Welcome back to the show. I know the subject matter today is a bit on the grim side, but that does not change the fact that I am beyond honored and even excited about the conversation that I am about to have today. It's with a guest who has been on my show before, for one of the most popular episodes I have ever had on this podcast, and for one of the most amazing topics that resonates with me, and that is lifespan and different things that affect our longevity.

Melanie Avalon:

I am here with Dr. David Sinclair. He is just an amazing human being. Friends, I'm sure you're familiar with him, but if you're not, he is a researcher at Harvard. He's co-creator of the Journal of Aging. He's been on Times' list of the 100 Most Influential People. He's the go to guy that I respect for basically everything in the biohacking, health, lifespan world. I had him on the podcast the first time for his book Lifespan: Why We Age and Why We Don't Have To. That is actually the only book, besides my own, that I own in all forms ever, print, Kindle, audiobook. It is just that necessary.

Melanie Avalon:

This is actually a true statement, David. When the whole COVID-19 thing first started and was becoming more real, literally one of the first thoughts I had, one of the very first thoughts, was "David Sinclair called this." I went to my book shelf, I pulled out Lifespan. I went to the chapter that you had, honestly, prophesying this. I took pictures of it, and I sent it to my family. For listeners, I'm just going to read to you a little piece from Lifespan. This is what I sent to my family.

Melanie Avalon:

In his book, David, he speaks about the H1N1 epidemic in 1918 and the significance of that. He says, "This could happen again, and given how much more humans and animals are in contact and how much more interconnected our planet is now than it was a century ago, it could happen quite easily. The gains in life expectancy we've witnessed over the last 120 years and those to come could be wiped out for a generation, unless we address the greatest threat to our lives: other lifeforms that seek to prey on us. It doesn't matter if we live decades upon decades longer, if a pandemic quickly snuffs out hundreds of millions of lives, negating and even rolling back the gains and average lifespan we will have achieved. Global warming is a longterm, critical issue to deal with, but one could also argue that, at least within our lifetimes, infections are our greatest threat."

Melanie Avalon:

I remember when I read that, and it really resonated with me. Then when this all happened, I was just like, "Wow. You called it." David, thank you so much for your work, and thank you so much for being here.

David Sinclair:

Hi, Melanie. Thanks for having me back on. Appreciate everything you've said. Also, I've got a copy of your book. It's been great to read. Thank you.

Melanie Avalon:

Oh, thank you. That makes my day. Thank you so much. To start things off, I will refer listeners, I'll put a link in the show notes to the first interview I had with David, where we go more into his history and all of that because it's very valuable. So I will definitely put a link to that, but I'd love to just jump into the content today. To start things off, you obviously saw something like this coming. When everything with COVID-19 first started happening, even last year, at what point did you anticipate that it might become the pandemic that it has become? Did you see this coming earlier on? Was it later, when the numbers started rising? At what point did you realize that this might actually be a serious threat?

David Sinclair:

Well, honestly, it's been on my mind for a decade. It was pretty clear to me in December that this was going to happen and play out. My wife actually says she was worried earlier because she heard a very brief radio report while she was driving one day in late November, a report of this weird pneumonia. The two of us, Sandra is her name, Sandra and I are biologists. We tend to overthink things, anyway. When bird flu and swine flu came through, we were very much prepared. This time we were similarly prepared. We went out and got ready before things ran out in the shops.

David Sinclair:

I do remember going through the supermarkets when this was very clear that it had made it across to our shores here in the US. I don't know if you've ever had this in your life, if you've had a revelation, or you know something that no one else does, and you look around like it's a movie, thinking, "Everyone else doesn't see what's coming. Wake up! Wake up!" There I was with a pretty big cart full of food, and people looking at me like, "This guy is panicking. What's his problem?"

Melanie Avalon:

Yeah, it's so true. I think it's one of the main issues right now with this whole thing. On the one hand, we have people who ... Well, I think now people are more aware of how serious it is, but on the one hand there are people who think or thought it's not a big deal. It's just the common flu. Then you have people who think they're never going to ever leave their house ever again. It can just be hard to know, as an individual, like you said, am I overreacting? Is this serious? I think what I'm trying to do, at least with this podcast, is not perpetuate fear and anxiety because I don't think that helps anything, but put the facts out there. What is real? What can we do about it? I think you're one of the best voices to do that.

Melanie Avalon:

To start things off, I'm so intrigued. I've been actually wanted to have an episode about this topic, regardless of COVID-19. This is actually pretty appropriate. I'm very fascinated by the difference between bacterial and viral infections and what those do in the body. That's a foundational question. What is the difference between a bacterial and a viral infection?

David Sinclair:

Let's start with what the difference between a bacterium and a virus is. They're both very, very ancient organism, but viruses might be even older. Their only existence continues because they hijack other cells, so therefore they need to be inside other cells to reproduce, whereas bacteria don't. What's similar about them is that they're mostly good bacteria and harmless viruses. It's just rare that we get these pandemic strains that have the bad combo of having a long incubation period and some fatality.

David Sinclair:

You can think of bacteria as they are at least 10, sometimes 1000 times bigger than viruses. They're really quite complicated little organisms. Of course they reproduce. They have their own special chromosomes, that they can copy themselves. They take in energy, and they divide. They're going to be around a lot longer than humans on this planet.

David Sinclair:

Viruses are just a package of genetic material with enough proteins just to get inserted inside the cell and then basically hijack the cell, which means they can be very small. In fact, they prefer to be small, those viruses, because they can be carried very easily in breath. That's the problem with the coronavirus, is that it's so small. Unlike a bacterium, which would eventually sink to the floor, a virus can be carried around in mist. If you've ever gone out on a day where it's cold and you can see your breath, viruses can hang out there for half an hour before they reach the floor.

Melanie Avalon:

Question here. You spoke about how viruses prefer something. This is something that haunts me. Viruses are not alive. Is that a correct statement?

David Sinclair:

Correct.

Melanie Avalon:

What drives them? I'm just very confused about ... Is it like they're artificial intelligence? What keeps them going? How do they even have a motivation to replicate and mutate and do these things if they're not alive?

David Sinclair:

Yeah, they're not. Don't even think of them as life. Think of them as just ancient biological material that, unfortunately, has grown up with life, and they hijack us. They don't have a mission. They don't have any consciousness. They are just a package of biology that probably started hijacking cells before there were even cells to begin with. You can imagine in the primordial soup, where cells are just starting to form, that there'd probably be other biological material that would hijack those original lifeforms. Those remain as viruses throughout the world.

David Sinclair:

They only exist because they're so bad at ... Well, one of the reasons they exist is that they're so bad at copying themselves. They make a lot of mistakes copying their genetic material, which, in the case of coronavirus and HIV, for example, they're based on very primitive genetic material called RNA, rather than our DNA. RNA is very good at storing information, and when you copy it, because there isn't a backup copy like we have in our cells, because it's double-stranded they make a lot of mutations.

David Sinclair:

That's an advantage to a virus. For us, it'd be terrible because we'd get cancer in our teens. But for a virus it's great because they've got trillions of copies of them. All you need is one change, and you can jump from one species to another. Over millions of years, if your species that you hang out in goes extinct, you're screwed if you're a bacterium that has to survive on that animal or plant. But if you're a virus that can jump from a bat to a human, or to a horse, to a pig, to a penguin, then who cares if humans go extinct? Who cares if bats go extinct? You'll just keep going. They've been infecting dinosaurs all the way through to us.

Melanie Avalon:

Do some viruses contain DNA, or do all contain RNA?

David Sinclair:

Some have DNA, yeah. There are more advanced ones. Some of them copy their RNA into DNA, once they get into the cell.

Melanie Avalon:

That was my next question was, could it become DNA.

David Sinclair:

It could. Those are called retroviruses.

Melanie Avalon:

Oh, okay. Oh wow. I'm learning so much. I've definitely heard that term before. As far as the viruses go, a normal human being, I know you talked about there's all these different viruses, do we normally hold a ton of potentially pathogenic viruses, or viruses that could cause health conditions? What determines why a certain person might become symptomatic from a potential detrimental virus and another person doesn't?

Melanie Avalon:

I know, for example, I had a viral panel done probably two years ago, and it showed which viruses I had in my body and which IGM versus IGG antibodies I had. I just found that so interesting, that we could harbor these viruses and have active antibodies to them or not, and we could be symptomatic or not. What determines, with any given virus, whether or not we're symptomatic?

David Sinclair:

Well, that's the trillion dollar questions today, with coronavirus. There are a number of factors. There are a number of stages that the virus uses to get us. The first is transmission and infections. So they need to get into the cell. Once they're in the cell, how well they replicate. Then just as important, how well do we recognize cells that are infected. Our body actually kills cells that are infected, but because the viruses are inside, it's actually quite difficult. They can hide in there, sometimes for decades, but not in the case of coronavirus. Then the fourth thing that our bodies have to do is to attack the virus in the blood and attack cells that are infected, but not attack the cells that are not infected. All of those are components that determine the course of the disease.

David Sinclair:

Now, the best thing you want is that it never gets into your cells in the first place. We don't know if that's true for coronavirus, but in the case of HIV and the development of AIDS, there are people that are mutants, have genetic mutations that block the virus from getting in. They don't have the protein that the virus seeks to use as a lock with their key. Probably, interestingly, because the plague back in the Middle Ages used the same lock protein, called CCR5. Those people that survived were the mutants, and many of us have inherited that.

David Sinclair:

With coronavirus, it looks like we all have this ACE2 lock on our lung cells, and it can get in. But it can depend. If you're predisposed to having high levels of that ACE2 protein on your lungs, you probably have a greater chance of catching it, and it being a worse infection. We can go through the various stages of biology, and it can all be different between us. One thing that seems to be important is the age dependency. Older people and obese people are more likely to have a worse case, particularly for going on respirators.

David Sinclair:

Nobody knows the answer to that, but one thing that happens typically is there's an overreaction of the immune system. Older people don't seem to be able to switch off their immune system, and what happens is, it's called the cytokine storm. Then cells of your body, the immune cells, start attacking healthy tissue as well. That's where patients can go from relatively healthy to dead within hours. Actually doctors have a tool to combat that. It's a drug called Actemra, which dampens that storm.

David Sinclair:

That's a long winded answer to say there's many differences between people, and we don't yet understand what it is fully between the young and the old that makes older more susceptible to this pathogen.

Melanie Avalon:

Okay, so many followup questions to that. To clarify, with the symptomatic versus asymptomatic, when a person is asymptomatic, does it mean they never "accepted" the virus into their cells? Or can a person accept the virus into their cells and still be asymptomatic?

David Sinclair:

Well, I think most likely, with this disease, because we all have the receptor as far as we know, that you'd be asymptomatic because your body rapidly got on the job and identified the infected cells in your throat and your nose and neutralized it and didn't have an overreaction at all. That could just be that your immune system is perfectly primed and you have the right T cells that amplify up quickly. Whereas as you get older, and if you're not in good shape, your immune system doesn't amplify quickly. Even though one cell might say, "Oh, I found an infection. I found the virus," they don't amplify up very quickly because those cells are older.

David Sinclair:

One of the things in my book that I describe, you'll remember well, is that older cells are not able to turn on the right genes at the right time. They've got a screwed up software. I think that's part of the issue, is that. Now that raises the question, if you could reset the age of the immune system, or one day the entire body, would people, 80 year olds, 90 year olds, even 100 year olds, succumb to COVID-19? Probably not. It's about the loss of youthfulness that's the problem.

Melanie Avalon:

Okay, that makes a lot of sense. So when the elderly, for example, are succumbing to coronavirus, it could be possibly from this loss of information, or their immune system just not being able to address the virus because of all the craziness in the immune system. It's just not able to officially deal with it?

David Sinclair:

Right, at multiple levels. First, in the initial ramp up, and then slowing it down and stopping the overreaction. Older people are defective in both.

Melanie Avalon:

Question to that, especially with the immune system, which I am so fascinated by, there's often discussions of the TH1 versus the TH2 aspect of the immune system. I feel like there are people that say they never get sick, for example, and then some people who feel like they are chronically ill, but they never get infectious. It looks like their immune system is reacting to almost everything all the time. Is that an indicator of anything? For example, if a person feels like they never catch the flu, does that pretty much indicate that they have a strong immune system? Then somebody who, like I said, feels like they are sensitive to everything, like their immune system is attacking everything, is that also protective?

David Sinclair:

Wow, gosh. So here's what I know as a biologist, but not as an immunologist. First of all, like you said, there are helper T cells, TH1, H stands for helper, and TH2. The balance between the type 1 and type 2 seems to be very important. It's extremely complicated to understand. And there's all these other types of cells, like regulatory T cells, which are called Tregs. But yeah, your TH2s will generally lead to B cells that produce the antibodies. TH1s will produce the inflammatory cascade, like interleukins, and also produce those memory T cells, which will stick around for years and remember that this has happened. I think that the imbalances you're referring to does lead to either a super high active immune system, but it can backfire as you say. You can have overreaction.

David Sinclair:

I'll tell you one thing that is in my area of expertise, which is the immune system of people who are healthy into old age. Some of those people are called centenarians, the ones that live over 100. When you ask them or look at their medical records, do they tend to get sick, or in their life did they remember getting sick, the answer is no. Being immune to regular colds and things that we typically get seasonally really is a good indicator of longevity.

David Sinclair:

This is anecdotal, but I think it will be more relevant when talking about the molecular biology. Since I've been living a much healthier life, especially over the last five years, I very rarely get sick. I can only remember one time that I got a cold, and I haven't had the flu or anything. I'm traveling and shaking hands often. I think, just base don my own body, that you can improve your immune system by how well you live.

Melanie Avalon:

Yeah because I know in our first conversation about lifespan and the topic around that, we talked a lot about your theory about aging as a loss of information. There was the question of is it bringing back information that's lost, or what is actually happening there? But now I'm really applying this to the immune aspect. For example, do you think if we had the technology with the immune system ... Do you think there's a loss of information in the immune system as well?

David Sinclair:

Well, we haven't looked, but some people have looked at the ability of immune cells to remember the type of cell that they are. We have what are called hematopoietic stem cells, HSCs. They make all the different cell types that we just talked about. The problem is two-fold as you get older. One is that those stem cells start being biased. They produce one type but not the other.

David Sinclair:

The other thing that happens that's really becoming clear is important is ... Normally we have thousands of different types of immune cells that have recognized different pathogens in our lifetime. They're producing IGG, which you mentioned, Melanie. As you get older, the types of cells you have compete with each other, and some outgrow the others. There was even the case of one older person who had only one type of immune cell left. They were all clonal, derived from one particular lineage. When that happens, you don't have this diversity of immunity. That's when things go really bad, especially with a pathogen that your body has never seen before.

Melanie Avalon:

Oh wow, okay. That taps into so many things. The reason I'm so fascinated by this is, this idea of resetting the immune system, especially with our previous conversation, I feel like there's so many people with autoimmune conditions or dis-regulated immune systems. It's just haunted me. Could you modulate the immune system? Or could you literally reset it? If so, would it remember what it had before? Is there the potential to completely reset it? Question about that, we know, I guess we know, we think that COVID-19 came from a bat.

David Sinclair:

For sure, it came from a bat. Yeah.

Melanie Avalon:

I was fascinated, I was reading in your newsletter, which by the way listeners, get on David's newsletter. It's the best. It's just incredible. You were speaking in your newsletter about the origin of COVID-19 in a bat. You were talking about the difference between immunity in a bat versus a human. I just found that so fascinating. You were talking about how bats have all of these viruses, but their immune system is much more tolerant. What are the indications of that? If a human had an immune system like a bat, that was more tolerant of viruses, would we die? How are these bats still living, if they're tolerant of these ... Oh, is it because they don't have the receptors that the viruses are attaching to, to do damage?

David Sinclair:

I think they do. I think the difference is that bats have had CoV-2 for a long time. Any bat that wasn't immune has long since died, maybe hundreds of years ago, if not longer. Bats put up with these things.

David Sinclair:

We have corona viruses in our world, too, they just typically aren't dangerous. They give us a runny nose, and we sneeze a bit, pass it on. We're resistant, so we don't die from the common cold typically. But those are corona viruses that we've seen before in our evolution and often when we're just kids. You have kids, you see them have a runny nose, you don't think about it. That's your body getting used to having corona viruses in the environment.

David Sinclair:

The problem with this particular coronavirus, SARS and MERS, is that they are different enough that our bodies have never seen them before. I think in future, people will be more immune. There will be survivors that, if this keeps happening in the 21st century, and then we'll be like bats. We'll have SARS going around our planet, and we won't think much of it.

Melanie Avalon:

To clarify quickly for listeners, what is the difference between ... SARS is the virus, and then COVID-19 is the disease from the virus?

David Sinclair:

Right. So the virus' full name is SARS CoV-2, corona virus number two. SARS1 was the one that was earlier in the 2000s, that came out but didn't spread, fortunately. But they're very similar. They're relatives of each other. They both bind to this ACE2 protein on our lung cells.

David Sinclair:

The other one is called MERS, which is slightly different. It's now existing in camels. It gets into cells using the DPP4 protein, which is a different lock and key. It's a different category of virus. But yeah, SARS just stands for severe acute respiratory syndrome, corona virus number two. The disease is COVID-19, as you said. Somebody thought 19 means it was the number 19. No, it was 2019.

Melanie Avalon:

Oh, okay. The ACE2 receptors that you spoke about, and you said different people have different amounts, what's the factors there? Do we need those ACE2 receptors? Is it okay if we down regulate them?

David Sinclair:

Well, based on the fact that everybody has them, we probably need them. What we know is that there's a couple of these ACE proteins. One is called ACE1, the other one ACE2. ACE1, when you down regulate it, it also brings your blood pressure down, and it seems to protect people against cardiovascular disease. ACE2 does the seemingly opposite, though. It's a pretty complex system, but that's the best way to think of it. The drugs that your parents, your grandparents might take, or you might take, they inhibit ACE1, typically. They're not inhibiting ACE2. But there's been concern, and today even there's back and forth about whether this is true or not, but still people have speculated that people on ACE1 inhibitors might ramp up the amount of ACE2. That would be potentially a bad thing.

David Sinclair:

But check the news. Go to the CDC website. It looks to me like today there was a paper that came out, I think it was in Science magazine, or at least it was an opinion letter, that said that there's no need to worry. The American College of Cardiologists I believe recommends that people don't change their medicine at this point. There's no reason to panic.

Melanie Avalon:

Would that go as well, you think, for natural supplements that might be affecting those ACE2 receptors? I know, for example, vitamin D, which I feel like plays a huge role in immunity, but it also has the potential to upregulate the ACE2 receptors. Would that be anything to be concerned about?

David Sinclair:

My view, and having read a lot of scientific papers on this, is that vitamin D deficiency would be really bad right now, if you were to catch it. Most doctors, including my regimen, have vitamin D in their protocol. I'm taking 2500 units, I use a day. I know of somebody who's a doctor who's taking 10000. But don't just go crazy and overdose on vitamin D because even that's possible. Just stay within the recommended amounts, which I think are what I'm taking. But yeah, most doctors actually would recommend vitamin D right now.

David Sinclair:

There's been a great report from three doctors in the UK, who outlined all of the reasons that I just were referring to. Plus they did something interesting, which is they looked at the correlations between parts of the world that have high vitamin D levels and not. They could see that places like Italy, which have very low vitamin D levels, surprisingly, in Europe, were the worst case fatality rates.

Melanie Avalon:

That was my next question, was geography potentially and vitamin D levels palying a factor there. That's so interesting because now I'm thinking back. I did some immunotherapy with a holistically minded MD before, and during that protocol, I wasn't supposed to take any supplements, but I was supposed to take like 10000 units of vitamin D every day. I didn't know why, but I guess it had something to do with the relationship between vitamin D and the immune system.

Melanie Avalon:

I do miss, I know the social distancing and everything is obviously very, very important right now, but what I had been doing, and I say this with caution because I know people get very nervous about tanning beds and such, but during the winter I would go to the tanning salon and go for just like one minute in the UVB bed, the ones that stimulate vitamin D production. I found that, I don't know, really helpful. Obviously that's not an option right now.

Melanie Avalon:

I actually just read something today. It was right before our call, so I was not able to even remotely synthesize the information presented in it. I was like, "I'll just ask you." It was a new theory. Basically it was saying that the cause of death, or the main issue with the coronavirus, wasn't actually so much the ventilator aspect and the lung issue, as how the virus was affecting our iron levels in our blood oxygen, and that that was the root cause here. Do you have thoughts on that? Have you seen information about that?

David Sinclair:

Yeah, I think I was the first person in America to talk about it. It was back in ... Well, if it's wrong it's not a good thing, but it was March 16th, anyone who wants to look at the thread that I put out on Twitter. What I found was a paper came out that day from China, I think it was that day; it was pretty fresh. What they found was, when they looked at the genes of the virus, they could model it and predict that, or at least hypothesize, that the virus was attacking the iron in the red blood cells, the heme. My recommendation at that point was, make sure you're not deficient in iron and that perhaps chloroquine is helping with the maintenance of the red blood cell activity. I think today somebody came out with that idea?

Melanie Avalon:

Well, I just read the article today, so I'm sure it was not ... It was before then, but I saw it for the first time today.

David Sinclair:

Don't feel bad. I saw somebody forwarded me an article on it just today, saying, "Have you seen this?" It seems to be a theory that's gaining traction.

Melanie Avalon:

I wonder if it was the same article. It's possible. Yeah, no, I was fascinated by it. With the hemoglobin and the iron and everything, is it kind of related to what you were saying about the cytokine storm and the oxidative damage and the inflammatory response? Would the damage from the relationship to the iron, is it a lack of iron, or a lack of blood oxygen? Or is it the oxidative damage from iron not being properly utilized?

David Sinclair:

I don't know the new article, but what I read was that the gene number one and the gene number 10 in the genome, and there are about a dozen of them in the genome, they actually were predicted to physically pull the iron out of the red blood cell. You'll remember back to biology days, heme is the molecule that is in hemoglobin, which is a protein. That iron that sits in there is what carries the oxygen around in your red blood cells. The virus needs iron, so it seems to suck it out of the red blood cell, which is a double whammy because you're suffering because if you go into the ICU, your lungs are filled with damaged cells and mucus, and you're not getting enough oxygen. Then what oxygen does get into your blood stream may not be able to be transported around.

Melanie Avalon:

Would that indicate that a really good ... I mean, it's hard because we're stuck at home, but lifestyle practice would definitely be, going with right now, exercise to oxygenate our blood and keeping all that going?

David Sinclair:

Oh, 100%. Yep. I've tripled my exercise, in part because I'm not on planes anymore, but it's really important to move. If I could put it down to one word? Move. Get out if you can. Go for a walk. If you can't, do the ... What do you call them? Star jumps? Jumping jacks? I forget what they're called here.

Melanie Avalon:

I've heard you say that on a lot of podcasts. I love that word, star jumps. Jumping jacks.

David Sinclair:

Jumping jacks, yeah. That's the minimum you can do. I told you just before we went live, I was down in the gym. I have a personal trainer who now talks to me over video. He puts me through a pretty hectic or difficult workout that involves weightlifting but also a lot of big muscles, so my legs, body, hips. I'm panting while I'm weightlifting. That's all good. I mean, you can do that at home. If you don't have weights, find something heavy. If you don't have something heavy, do squats, this kind of thing. Now's the time to do it, for sure. You'll come out of this pandemic being stronger and fitter for it.

Melanie Avalon:

Yeah, I love that. That's something I've heard you discuss on other podcasts, and it really, really resonated with me. It's this idea that we could see this time of quarantine and being stuck at home as fear, anxiety, and just eating food and watching Netflix and all these things.

Melanie Avalon:

Or we could see it as a time where we are finally ... We're always complaining about a lack of time, but now we have time. We could actually use it to grow stronger. We could start new exercise practices. We could do all these fun tasks or to do lists that we've been wanting to do. I know it's hard with this quarantine lifestyle, but I think we can definitely refrain and, like you said, grow stronger for it. Now is the time for that.

David Sinclair:

Yeah, and eating well. It's harder than usual, I find, but yeah, don't overeat. Try not to eat all the bad stuff. Though I'm guilty of doing that. It's just too easy to say I'm going to watch a movie and get a snack.

Melanie Avalon:

Speaking to that, eating. How do you feel about intermittent fasting during this time? There's been some discussion about whether or not longer fasts might be problematic. I know when I was doing research for my book, I was researching the hunger response to infection and how it might differ, based on bacterial or viral infections.

Melanie Avalon:

I was fascinated by some of the research that I was reading, saying that in general it seems to be pretty intuitive. If you're feeling sick and you're not hungry, there's a reason for that. Then I was also reading that some viruses, they think might be able to hijack the body's natural hunger response so that you don't feel hungry, but you actually should be eating. Which, I was like, that's really shocking. That's not good.

Melanie Avalon:

Speaking to that, how do you feel about ... I know a lot of my listeners, and me as well, practice intermittent fasting. Do you feel like intermittent fasting daily is okay? Are longer fasts an issue?

David Sinclair:

I think really long fasts would be an issue. I've studied caloric restriction, which is chronic hunger. Those animals don't do well, when they get infected with at least bacteria. We haven't tested viruses. The study you refer to, from 2016, was a great one. They looked at bacterial versus viral infections, and their conclusion was that what you tend to eat during those infections is beneficial. You can either lose your appetite or not. If you have a viral infection, it was better if ... I think it was mice. The animals, if they ate, it was better with viruses, and if they were fasting, it was better for bacteria.

David Sinclair:

It's a little different here, with the coronavirus. If you're not sick and you want to prepare to be ready for getting the infection, and probably half of us are going to get it eventually, you want to keep your blood sugar levels from getting really high. Type 2 diabetics are suffering more, having worse scenarios in hospital. I think in general, keeping your blood sugar levels at a reasonable level is always a good thing, if you're about to be attacked by anything, bacteria or virus.

David Sinclair:

Getting back to that iron question. It was hypothesized, and to me it makes a lot of sense, that if you have high levels of blood sugar, you're actually going to modify your hemoglobin with sugar. In fact, when you get a test for type 2 diabetes, they measure what's called glycated hemoglobin. It's called HbA1c. Anyone who's had a diabetes test will know this, and they monitor it regularly. It could be that having defective hemoglobin that's covered in sugar, from high blood sugar, makes things worse.

David Sinclair:

Summary is, I think intermittent fasting in a mild way, which is what I do, I skip breakfast and eat a healthy small lunch, is perfectly fine. If you get sick, if you're in hospital, all bets are off. You don't want to be fasting under those conditions. You'll do what your doctor suggests.

Melanie Avalon:

I was asking listeners for questions for you, and that was a question somebody asked. They wanted to know, if they were admitted to the hospital, should they eat the hospital food or should they fast?

David Sinclair:

We know how bad that can be, but all jokes aside, yeah, you'll need the energy. You don't want to be using your reserves, I don't think. Especially if you're elderly. That would be my guess. I'm not an MD of course. I'm just going based on a lot of reading of science and having studied this for a while. In general, when there's a life and death situation, you want to be paying close attention to what the doctors are saying. They have far more experience with critical conditions. You and I, Melanie, we specialize in when you're in your prime of life, typically of how to maintain that. What we're saying is, in preparation, in case you get sick.

Melanie Avalon:

Yeah, and also speaking to that, the blood sugar regulation, it wasn't in context of viral infections, but I've been emailing back and forth with ... He's your friend as well, I think, James Clement. He said to tell you hi. We were discussing some articles, looking at them last night, actually, this is bacterial not viral, but it was about the correlation between blood sugar levels and the endotoxin response to a meal. It was really fascinating. Basically those with diabetes and blood sugar regulation issues seem to experience higher levels of bacterial related endotoxin for sustained periods after a meal. Again, that's bacterial, but there just seems to be this huge relationship between blood sugar regulation and everything.

David Sinclair:

Yeah. That's a fascinating study.

Melanie Avalon:

Yeah, I can send it to you. It was really, really interesting. It was in the context of saturated fat and the potential of dietary fat to affect endotoxin in the body, and then how blood sugar played into that.

David Sinclair:

Yeah. Well, we know certain foods will be inflammatory. If you're obese, you'll have more inflammation in your tissues to begin with. I think getting your body's inflammation down but your immunity up is the key. That's why I'm doing what I do.

Melanie Avalon:

Quick question, you mentioned about half of the people are going to get this. I've heard half, like you say. I've heard everybody is eventually going to get it. So you think about 50% of people will eventually get it?

David Sinclair:

Yeah. We're not all going to get it. That would be impossible.

Melanie Avalon:

Really? Okay.

David Sinclair:

Unless they shoot us up with it. The numbers vacillate depending on the models, between a third to have herd immunity, for the R0 to go down below one, which means it'll peter out on its own, to 75%, which is what Angela Merkel said that freaked everybody out back in March. It's somewhere in between. This isn't mathematical. This is more me trying to guesstimate. The more people I talk to, the more I hear of friends, family, doctors who tell me that there's a lot more asymptomatic people than we thought, or mild symptoms where it's maybe a bit of a fever and a headache for a few days and that's it. Those people don't report themselves to the government. It's probably the last thing they want to do. So there's a lot of people who have already had it.

David Sinclair:

I think that what's going to happen is, those of us who don't catch it for the next nine months or so, that it'll be petering out. You've probably got to wait 18 months before the vaccine. Now it's about 17 months. Yeah, it's a long time to go without catching it. What's probably going to happen is that, by the end of this year, those people like me who meet a lot of new people or travel or are on planes, we're going to get it, and those people who live in a basement and work from home are going to be able to avoid it.

Melanie Avalon:

Yeah, that's a big question a lot of people have been having. This is all happening, and then they say, "Oh, I feel like I had ..." They think they had it already, before it was kind of well known. I know my family, they traveled in Europe a few months ago, and they all got this thing, which now they're ... I don't know. My mom feels like she has it currently. So it is possible that people have had it already?

David Sinclair:

Oh, without a doubt. We're underestimating the number of cases. When people talk about the case fatality rate, the cases are only the ones that enter the medical statistics. People like your family and my friends who've had it, they're not in the statistics. We don't know what the infection fatality rate is. The more people that don't report it, the lower the fatality is. We're definitely below one percent fatality, because of those numbers. It'll probably be even less, but it's still a bad virus. It's still five to ten times worse than flu.

Melanie Avalon:

Okay, so being five to ten times worse, you mean from like a fatality or from the symptoms?

David Sinclair:

No, just fatality. Plenty of people die from flu each year as well, but I hear anecdotally that even for somebody my age, at 50, it still feels like the worst flu you've ever had. It can be. It's not to be taken lightly for anybody who's 50 or older. People in their 20s, generally, unless you've got some underlying thing that you may not even be aware of, will just be sick for a few days like it's a really bad dry cough, headache, not feeling very energetic, don't feel like getting out of bed, maybe a little bit of breathlessness. You might have diarrhea. Other than that, you get over it after about a week or two.

Melanie Avalon:

Because the virus does affect the lungs and people ultimately might need ventilators, do you think that's the reason that the system seems to be collapsing? For example, if the virus didn't affect the lungs, if it was equally fatal, but maybe it just attacked the GI tract, and so you didn't need ventilators to keep people alive, do you think that would have changed the hospital response and hospitals getting overwhelmed?

David Sinclair:

Yes, that's a very important point, is that our lungs are particularly fatal when they don't work. You can't just pull out lungs. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome, is one of our achilles heels, as mammals, or as any animal that lives with lungs on the surface of the planet, rather than under the ocean. One of the problems with us, besides not having enough respirators, the problem for elderly, if you look at the biology, is those air sacs that are very minute, they're tiny, millimeters in size, they can collapse or fill up pretty quickly. We need them to be open. We need them to have a gas exchange. Once you get damage to the lungs, they can very quickly be problematic.

David Sinclair:

Even with the respirator, you're pumping high concentrations of oxygen into the lungs. Even that oxygen doesn't diffuse across, if there's a lot of cellular damage, fibrosis, and just debris mixed with mucus. Sometimes the ventilator isn't enough.

David Sinclair:

The other thing that happens with the ventilator is that the longer you're on it, the less chance there is of getting off it. I know this from my mother's experience. She was on it for I think two weeks or 10 days, and that wasn't good. She eventually passed away. If you have a loved one who's on a ventilator, what you want to hear from the doctors is we're going to take the person off hopefully within a week, sometimes two weeks. Longer than that, the body seems to get used to not breathing on its own, and it's hard to come off it.

Melanie Avalon:

Okay, so I have two quick thought experiments for you. The first one is, as far as social distancing and stopping this virus, if hypothetically, I know this could never happen because we are human, but if everybody literally stayed at home, literally, for four weeks, would that stop it?

David Sinclair:

Yes.

Melanie Avalon:

Wow, okay.

David Sinclair:

The fact that it's still spreading means that, A, we know people still have to run the country and make the water supply and the internet work, but that's not the whole problem. There are still people out there who say I don't care, or I'm going to get it, or I want to go see grandma, or let's have an Easter celebration, which is coming up. That's what's leading to the spread. It's not the 95% of us who are being good about it.

Melanie Avalon:

Okay. I know, that's the thing. I remember this exercise, which is one of the most profound exercises I've ever done in my life. It was at a camp I went to when I was little. It was basically everybody, we went in a circle, and we held out a finger. They put a hula hoop on our finger, so we were all holding up this hula hoop. Then they told us, "Okay, lower the hula hoop to the ground, but you can't ever not touch the hula hoop." What happened was, A, it was impossible for us to lower it to the ground because in order to lower it, you have to lower your finger, but you can't lower your finger unless everybody lowers their finger at the exact same time. What happened instead was, the hula hoop would magically rise. Once one person started lifting their finger up, it just kept rising because you had to keep touching it.

Melanie Avalon:

Basically the takeaway was that the only way to lower the hula hoop was if, the way we solved it was, we had to all agree, literally at the same time, to lower it an inch, all at the same time. One person couldn't not lower it. It was such a profound experiment for me because I was like, "Wow." This just showed me that something like this, everybody literally would have to commit to it. One person might think that that doesn't make a difference, but it does. It was just fascinating.

Melanie Avalon:

Really quick second thought experiment. The social impact of social isolation, do you think hypothetically, let's say for example that this virus was not transmitted by people, you just caught it in the air. Do you think if there wasn't this aspect of social isolation, and seeing our fellow human beings as threats, and not being able to have physical touch, and not being able to have this profound need for social support and connection, if the virus transmitted regardless of touching, so we still had social support. Do you think that the fatality rate would actually be lower because we have social support?

David Sinclair:

A little bit. I think that the virus doesn't really care. We may have a little bit better immunity, but we're dealing with a pretty formidable foe here. If you put power on it, the virus is 99, and then I would ascribe one percent or something like that ... I don't want to dismiss your theory because I think it's a good one to talk about, but I'm just thinking that it's very hard to prevent being infected. You might have better immunity, but still, it's going to be pretty hard mentally to overcome the disease. It might have a little impact.

Melanie Avalon:

Maybe it would have more of an impact for susceptibility to future illnesses, just because of the immunity aspect, I wonder.

David Sinclair:

Here's a good point, or a good discussion. We don't have to be socially isolated. We have technology. I think most people have a computer and the internet. Not everybody. We, as a family, when this first happened and we moved away from the cities together, my brother is back in Boston, I'm down here on Cape Cod in Massachusetts, we all got ourselves these devices. I won't say their name, but a little picture frame where you can video chat. We just put that in the kitchen. So whenever we're cooking dinner or whatever, we call each other, and we can all be on the same thing.

David Sinclair:

That's using technology. Thank goodness we have the internet. Imagine if it was 1970. We'd have to call each other on the phone, and we all know how painful that can be. I think that we often forget that we can still stay in touch with our loved ones, even if they're on the other side of the planet. Every night we make it not a chore but a ritual to call each other, even if maybe we're tired or we don't feel like talking. It's important.

Melanie Avalon:

I think that's so incredible. I know we're running out of time. I just have some really quick rapid fire supplement questions. You've spoken before, and there's information out there, about humidity and the mucus membrane in the lungs, a lot of my listeners and me as well take a supplement called serrapeptase, that clears your sinuses, gets rid of congestion, gets rid of mucus. Is this actually a time when it might be a good thing to be mucusy and congested?

David Sinclair:

Oh, so this increases your mucus, does it?

Melanie Avalon:

No, no, no. It's serrapeptase. It's a proteolytic enzyme.

David Sinclair:

Oh, it's digesting. Got it.

Melanie Avalon:

Yeah, and it's a wonder for clearing out your sinuses. It's a game changer for me, but now I'm like, "Oh, maybe actually I should not be doing anything that might be clearing out mucus."

David Sinclair:

Ah, okay. That's fascinating. Yeah, actually one of the things that a company that I co-founded is something similar, to help with COVID patients, to get rid of the thick mucus that develops.

David Sinclair:

There's two stages to this. The first stage, where you're going through the shopping center or somebody coughs near you in the elevator, or you touch your face, that's where you want a lot of mucus lining your throat and your nose and your lungs. What happens is, the mucus will trap the virus. There will be enzymes that kill the virus in there. We have these antiviral peptides in there. If you're lucky, if it's a very low dose, you may not even catch the disease, even if the virus gets up your nose.

David Sinclair:

That's one of the reasons for having moderate humidity, not low humidity in your house during winter. It's one of the reasons it's thought why flu and the cold come back in winter, is the lack of humidity and the mucus being very thin in your nose and in your throat. I know when I'm in winter and I don't humidify the house, I can really feel the mucus gone. So in short answer, you might want to lay off the serrapeptase.

Melanie Avalon:

Were you familiar with it, the serrapeptase?

David Sinclair:

It's from bacteria in silkworms?

Melanie Avalon:

It's a proteolytic enzyme from the silkworm. It's a wonder. I can send you studies on it.

David Sinclair:

I'll look at it. I'm speaking from ignorance, but a thick mucus is good to prevent the disease. Once you get it, you'll have a lot of mucus, especially building up in the bottom of your lung. That's not good, especially for those late stage patients where they're trying to get the air desperately into their bloodstream.

Melanie Avalon:

Okay, so maybe less serrapeptase if you don't have it, but maybe serrapeptase if you do have it. Those are my words, not yours. Just theories.

David Sinclair:

Yeah, if it works, I wonder why doctors are not using it.

Melanie Avalon:

It's shocking. It's amazing. Yeah. We can talk more about it later. Then really last rapid fire question, supplements I'm taking right now, that I know a lot of my listeners take as well, and it's things, a lot of them, learned from you. I'm taking liposomal NMN to support NAD, liposomal glutathione now. I have liposomal vitamin C, but I'm wondering if I shouldn't take that while fasting because I wonder if that would down regulate my body's natural endogenous antioxidant production. But just in general, are those supplements sounding good?

David Sinclair:

Right, so I'm taking vitamin C.

Melanie Avalon:

Yeah, what are you taking?

David Sinclair:

I don't take it at any particular time of day. I haven't thought that deeply about that. Sounds like you're ahead of me on that. But I take vitamin D, vitamin C. I'm taking the usual NMNs, the NAD booster, and resveratrol That's my standard go to. Anyone who's listening, page 304 of my book, you can see it all listed plus more. What am I doing in addition to that? Those are the basics. There's things like alpha lipoic acid I've been taking for a while, which boosts mitochondrial activity and also is shown to help with the loss of smell, which is a symptom of the disease. So I'm doing that. Those are the main things. You know quercetin?

Melanie Avalon:

Quercetin?

David Sinclair:

Yeah, some people say it-

Melanie Avalon:

Yeah, I love that.

David Sinclair:

Yeah. It's very similar to resveratrol. We found it also in the early 2000s can activate the Sirt1 enzyme just like resveratrol does, but it has other properties. Actually, resveratrol and quercetin have antiviral properties in cells, though I have to just declare a word of caution, neither of these have been tested in living human beings. If you do catch it, all bets are off whether it's going to help you or hurt you. Leading up to it, leading up to an infection, I'm all for those two molecules.

Melanie Avalon:

Do you think an intense sauna session, could that wipe out the virus if it was in you, potentially, because of the heat shock proteins?

David Sinclair:

Yeah, potentially.

Melanie Avalon:

I've been doing that every night.

David Sinclair:

Yeah, wow. You have a sauna in your house?

Melanie Avalon:

Have you heard of Sunlighten Solo saunas?

David Sinclair:

Uh-uh (negative).

Melanie Avalon:

It's like a sauna that an everyday person could have. It's a collapsible unit that you lie in. It's far infrared, and so it's great for people who can't afford a whole sauna, or are in an apartment or something. Game changer. Game changer. I'll send you a link to it.

David Sinclair:

Please, yeah. I'd love to see that. But yeah, potentially. Hot drinks. I'm drinking hot tea throughout the day. It helps with hunger. It helps with thirst. It's also good, you know that anything over about 60 degrees Celsius, I don't know what that is in Fahrenheit, help me, I'm Australian.

Melanie Avalon:

Oh, I'm really bad. I'll google it, put it in the show notes.

David Sinclair:

Anyway, as hot as you can drink. The virus isn't going to survive in that.

Melanie Avalon:

Okay, yeah. I've been doing that every single night, but I've really ramped it up now, especially with COVID. I had the founder actually on the podcast. That episode will be coming out soon. I'm so grateful for it right now. I can't even express.

Melanie Avalon:

I started this interview with a quote from your book. I'd love to end it with a quote from your book and ask for your thoughts on it. I know your time is very valuable. One of the things you said in your book, you were speaking about the potential for biotracking to prevent something like this pandemic, or pandemics in general.

Melanie Avalon:

You say that, "The tragedy of the commons is that humans are not very good at taking personal action to solve collective problems. The trick to revolutionary change is finding ways to make self interests align with the common good." I was just wondering, do you think that this pandemic might be the catalyst that we need for the world to embrace this idea of biotracking and having this preventative measure that we can take, with these biotracking type devices, to prevent this in the future?

David Sinclair:

I certainly hope so. I think the world, it's a little hard for me to judge because I'm already in the middle of the tornado, so it's been with me for the last 15 years. My guess would be that people who have never thought about their health, or never thought about the ability of a pathogen to kill them, or have thought about how a virus gets into the body, most people don't care about viruses on a daily basis, as we have in the last few weeks. That will naturally cause people to think more about their overall health and prevention.

David Sinclair:

When you're in your 20s, 30s, 40s, even 50s, you don't think about death much, usually, but we've all had to face the potential of dying. That's something that most people have really never thought of, not since they were four years old and they heard about death in the first place.

Melanie Avalon:

I think it's so profound. I'm just so grateful for the work that you're putting out there. I feel like, honestly, you're putting out the facts. You're keeping everything so relevant. But you bring in the sense of humanity and hope and positivity, and how we can grow from this and how we'll come out stronger. I've heard you talk about the Roaring Twenties are still ahead of us. I just am so grateful for you.

Melanie Avalon:

Last question, I promise. It's what I asked you last time, but this is the question I ask every single guest at the very end. I just think it's so important. What is something that you're grateful for?

David Sinclair:

Well, right now I'm grateful for the time that I can spend with my family. I'm usually on planes too much. The last few weeks have been wonderful. I've got three teenage kids, so being forced all together to eat meals and talk, it's just been a real gift.

Melanie Avalon:

That's so wonderful. Well, thank you so much. Thank you for your work, everything you do. I cannot express my gratitude enough. Are there any links you would like to put out there, or any way for people to follow you? I know you have your newsletter, which is amazing. Anything you'd like to put out there?

David Sinclair:

Yeah, so the newsletter and my book can be found at the website LifespanBook.com. I'm also on social media, as you know. I'm tweeting pretty often about new science, new discoveries that come out, especially about COVID-19. I'm not an MD, but I'm very good at reading scientific papers very quickly and finding connections throughout the world at various levels, and also a lot of friends on the front lines that give me information ahead of what you'd read in the media. Yeah, follow me there. I'm happy to do this as a service. I'm glad that there are some scientists like me who are trying to get through to the truth, because there's so much out there that isn't trustworthy.

Melanie Avalon:

I am glad there are scientists like you, as well. If you want to be a politician and run, I would vote for you. Just in case you're wondering. In any case, listeners, the show notes will be at MelanieAvalon.com/immunity. I will put links to everything there. Thank you so much, David, for your time. Enjoy this time of rest and recovery during social isolation, while still studying and learning and hopefully growing stronger. Hopefully we can talk again in the future, when we're on the other side of this.

David Sinclair:

Sounds good. You take care.

Melanie Avalon:

Thank you, David. Bye.

David Sinclair:

Bye.