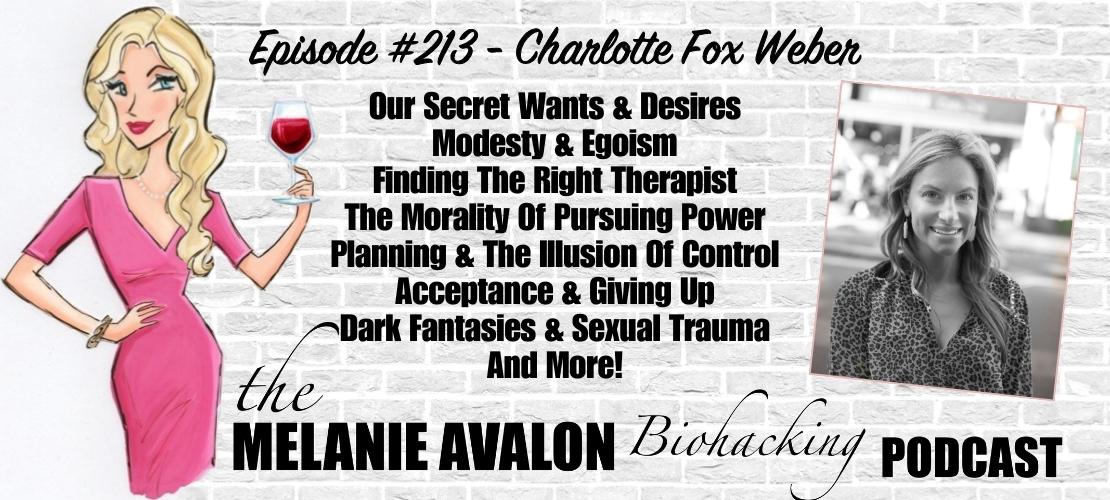

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #213 - Charlotte Fox Weber

I'm a psychotherapist and writer and momma of two boys. I live in London and I'm particularly passionate about the work I do with women in Senegal. I am from Connecticut and went to school in Paris and in the UK and for a long time I didn't know where to call home. I am particularly interested in social norms and cultural influences in exploring our narratives and ways of relating.

LEARN MORE AT:

@charlottefoxweberpsychotherapy

What do you secretly desire? | Charlotte Fox Weber | TEDxManchester

SHOWNOTES

IF Biohackers: Intermittent Fasting + Real Foods + Life: Join Melanie's Facebook Group For A Weekly Episode GIVEAWAY, And To Discuss And Learn About All Things Biohacking! All Conversations Welcome!

Follow Melanie On Instagram To See The Latest Moments, Products, And #AllTheThings! @MelanieAvalon

AvalonX SUPPLEMENTS: AvalonX Supplements Are Free Of Toxic Fillers And Common Allergens (Including Wheat, Rice, Gluten, Dairy, Shellfish, Nuts, Soy, Eggs, And Yeast), Tested To Be Free Of Heavy Metals And Mold, And Triple Tested For Purity And Potency. Get On The Email List To Stay Up To Date With All The Special Offers And News About Melanie's New Supplements At avalonx.us/emaillist! Get 10% off AvalonX.us and Mdlogichealth.com with the code MelanieAvalon

Text AVALONX To 877-861-8318 For A One Time 20% Off Code for AvalonX.us

FOOD SENSE GUIDE: Get Melanie's App At Melanieavalon.com/foodsenseguide To Tackle Your Food Sensitivities! Food Sense Includes A Searchable Catalogue Of 300+ Foods, Revealing Their Gluten, FODMAP, Lectin, Histamine, Amine, Glutamate, Oxalate, Salicylate, Sulfite, And Thiol Status. Food Sense Also Includes Compound Overviews, Reactions To Look For, Lists Of Foods High And Low In Them, The Ability To Create Your Own Personal Lists, And More!

Stay Up To Date With All The News On The New EMF Collaboration With R Blank And Get The Launch Specials Exclusively At melanieavalon.com/emfemaillist!

BEAUTYCOUNTER: Non-Toxic Beauty Products Tested For Heavy Metals, Which Support Skin Health And Look Amazing! Shop At beautycounter.com/melanieavalon For Something Magical! For Exclusive Offers And Discounts, And More On The Science Of Skincare, Get On Melanie's Private Beautycounter Email List At melanieavalon.com/cleanbeauty Or Text BEAUTYCOUNTER To 877-861-8318! Find Your Perfect Beautycounter Products With Melanie's Quiz: melanieavalon.com/beautycounterquiz

Join Melanie's Facebook Group Clean Beauty And Safe Skincare With Melanie Avalon To Discuss And Learn About All The Things Clean Beauty, Beautycounter And Safe Skincare!

BEAUTY AND THE BROTH: Support Your Health With Delicious USDA Organic Beauty & The Broth Bone Broth! It's Shelf Stable With No Preservatives, And No Salt Added. Choose Grass Fed, Grass Finished Beef, Or Free Range, Anti-Biotic And Hormone Free Range, Antibiotic And Hormone-Free Chicken, Or Their NEW Organic Vegan Mushroom Broth Concentrate Shipped Straight To Your Door! The Concentrated Packets Are 8x Stronger Than Any Cup Of Broth: Simply Reconstitute With 8 Ounces Of Hot Water. They’re Convenient To Take Anywhere On The Go, Especially Travel! Go To melanieavalon.com/broth To Get 15% Off Any Order With The Code MelanieAvalon!

MELANIE AVALON’S CLOSET: Get All The Clothes, With None Of The Waste! For Less Than The Cost Of One Typical Outfit, Get Unlimited Orders Of The Hottest Brands And Latest New Styles, Shipped Straight To You, With No Harsh Cleaning Chemicals, Scents, Or Dyes! Plus, Keep Any Clothes You Want At A Major Discount! More Clothes For You, Less Waste For The Planet Get A FREE MONTH At melanieavalonscloset.com!

SUNLIGHTEN: Get Up To $200 Off AND $99 Shipping (Regularly $598) With The Code MelanieAvalon At MelanieAvalon.Com/Sunlighten. Forward Your Proof Of Purchase To Podcast@MelanieAvalon.com, To Receive A Signed Copy Of What When Wine!

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #38 - Connie Zack

The Science Of Sauna: Heat Shock Proteins, Heart Health, Chronic Pain, Detox, Weight Loss, Immunity, Traditional Vs. Infrared, And More!

Tell Me What You Want: A Therapist and Her Clients Explore Our 12 Deepest Desires

finding the right therapist

first impressions with a new therapist

the stories in charlotte's book

charlotte's personal story with therapy

self Empowerment vs. pursuing power

the morality of power

Attraction to power

wanting to belong

discussing race in therapy

planning and the illusion of control

having a healthy relationship with time

the desire for attention

using Absence to get attention

attachments & wanting

the mixed messages given to women in society

modesty & egoism

people pleasing

faking in life or therapy

"giving up" & acceptance

liminal space

dark fantasies

sexual trauma

I Fell for a Famous, Much-Older Artist. Then He Got Violent

losing your youth and beauty

showing up authentically

trying therapy, and interviewing therapists

speaking up for yourself

TRANSCRIPT

Melanie Avalon: Hi, everybody. Welcome back to the show. I am so incredibly excited about the conversation that I'm about to have. This was a really fun, enlightening experience, friends, reading today's book. I am here with Charlotte Fox Weber. She's a psychotherapist and a writer. She co-founded Examined Life and she was the founding head of the School of Life Psychotherapy. And her new book is out and it is called Tell Me What You Want: A Therapist and Her Clients Explore Our 12 Deepest Desires. And so, when I came across this, I was immediately super intrigued and actually thinking back to the-- I'm trying to remember how I first connected with you, because I get a lot of pitches and I'm trying to remember if this was one where it was directly pitched or if I was looking through a lot of lists of books. But either way, I immediately gravitated to the whole concept.

Charlotte Fox Weber: I'm so glad to hear that.

Melanie Avalon: I really am. I was like, "Oh, I have to read that." I'm a huge fan of therapy. So, I've been doing weekly therapy sessions for about a decade now, and I just think it's such a game changer for me personally, for mental health and wellness and just having reflection on your life and the chaos of life and having a through line with somebody-

Charlotte Fox Weber: Oh, I love that.

Melanie Avalon: -that just makes sense of things. A third-party perspective that knows you really well but also can be a little bit more objective. Now I'm going on a tangent. I've also been really excited to see-- I feel like therapy has been stigmatized for a while. Even now I feel like some people think that only people "with problems" go to therapy, which is the craziest idea to me. So, in any case, I'm all about normalizing mental health and wellness and seeing therapists. And reading this book, I had no idea where it was going to go. But friends, it's really, really cool the way it's laid out. So, Charlotte goes through and uses, basically, case studies from her different clients that she's had, and how they represent these secret wants and desires that we universally all might have, or maybe that's a question, if we do universally all have all of them. But this conversation could go so many different ways. I'm really excited to see where it does go. Charlotte, thank you so much for being here.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Thank you for having me. And what an exciting introduction.

Melanie Avalon: So, like I said, I have so many questions for you. Oh, and side note, we were talking right before this. So, Charlotte, as readers know, I love it when authors narrate the book themselves, and Charlotte does narrate the audiobook, and she's a great narrator. So, definitely get it on audio if that's your thing on Audible, because I really enjoyed listening to it.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Thank you. I have a question for you already. In the past 10 years, have you been seeing the same therapist or is it different therapists?

Melanie Avalon: With moving back and forth, I think I've seen consistently four therapists. The most recent one was not because I moved, but in general, it's mostly been because I moved. I love mine now. I'm thinking of moving to Austin and one of the reasons I don't want to is I'm like, "I'd have to find a new therapist." [laughs]

Charlotte Fox Weber: That would be a loss. Finding a good therapist is definitely an important part of it being effective. It's everything.

Melanie Avalon: That's the other thing. Going back to that question or what I was saying earlier about the stigmas around therapy, I think a lot of people also will try to find a therapist. At least for me, I've had to "interview" a lot of therapists to find the right connection both ways for both of us.

Charlotte Fox Weber: I'm glad you did.

Melanie Avalon: Not to start on a bad note, but I've had some crazy first interviews with therapists.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Let's start on a bad note, because I began my experience of therapy with horrendous therapy. I think having difficult experiences of mediocre therapists is an undiscussed topic that should be acknowledged.

Melanie Avalon: Like I said, because to find therapist that I really love, I would go first sessions with multiple therapists. I even had a few instances where I feel like I need therapy from that first session with the interviews.

Charlotte Fox Weber: To recover from the traumatic therapy.

Melanie Avalon: Yes. I've had things said to me in first interviews that just blew my mind. [laughs] I encourage people. It's like dating, in a way, like, find the person for you.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Yes. And of course, it can be perfectionistic and idealistic, if you are constantly shopping for a therapist and waiting for the perfect one, because therapists will never be entirely, entirely-- I think it needs to feel possible. There can be greater understanding and rapport and connection.

Melanie Avalon: I agree so much. I feel like for me, I'm really intuition driven. So, when I did have that connection, I would just go with it. My current therapist, who I just love, I just immediately felt that it was the right person for me at that time in my life. I think the feeling of not feeling judged is most important for me. Like, the feeling of safety that I can just say anything and it'll be okay.

Charlotte Fox Weber: I feel like it's paradoxical, because it's when you feel safe with someone that you can-- then take the risk of going somewhere dangerous. Like, you need to have that comfort, so that you couldn't be disruptive and cannot just hold back.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. No, 100%. Do you take new clients now?

Charlotte Fox Weber: I, unfortunately, have been having to say no to new work, because I'm writing another book and I have a full caseload. But that said, I always struggle to say no to new work, because I love meeting new people and having the fresh experiences of just doing initial sessions. Sometimes, even knowing when someone isn't suitable, and I have a colleague I can recommend. I like being a therapy matchmaker just to unhumbly brag. I feel like I'm cupid when it comes to setting people up with the right therapist.

Melanie Avalon: When you do see a new client or a new potential client-- You talk in the book about the role of first impressions, and all the notes you take, and everything. Is it pretty immediate for you if you feel like you should personally work with somebody or does it take time to feel out that relationship?

Charlotte Fox Weber: I think that it takes time going both ways. I think allowing for the uncertainty can be important. There have been times when it's a beautiful start, and the first session is bursting with possibility, and then it can turn into something else. I feel like assessments can be problematic in that way, if there isn't the flexibility factor. In a way, it's like a relationship. When you sign up for marriage, you sign up for something at that point in time, but there should be a allowance for the fact that changes will occur, and there will be unforeseen situational stressors, and you don't know how it will play out.

Melanie Avalon: No, that totally makes sense.

Charlotte Fox Weber: That probably sounds so suspicious of me and I'm not a lawyer.

Melanie Avalon: No, I love it. I'm just thinking back. So, like I said, you talk about these different clients in your book. Did you use pseudonyms for the first names?

Charlotte Fox Weber: I definitely did. So, I have reconstituted clinical material, so that everything I write about is from actual work. But I've changed the details enough to protect confidentiality, so that it's not one person's story.

Melanie Avalon: Okay. I was trying to remember, yeah, if I read that in the beginning.

Charlotte Fox Weber: I obsessed over that issue for many months, and then finally felt okay with. I wanted to honor people's true stories, and be honest about therapy, and not just gloss over it and make it sound overly idealized. But I also didn't want to ask for consent. I'm not even sure that such a thing exists when it comes to therapeutic relationship.

Melanie Avalon: It feels very real. So, all of the moments and examples, are they pretty much all moments and examples from people?

Charlotte Fox Weber: So, they're all real. Everything is from clinical work. But when I say I reconstitute it, I would move a detail or feature from one clinical experience, and then apply it to a different clinical experience. I kept track. It sounds really obsessive and strange, because probably was as a process. Everything comes from somewhere, but I mixed it up enough, so that it's not the same features from the same person if that makes sense. Probably it doesn't.

Melanie Avalon: No. So, in my head, what I see is like this mosaic of all these different, the colors of the people, but then the colors are [giggles] blending into the other ones to create these different pictures.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Because there was something really important about the integrity of actually writing about real therapy. I didn't want it to be fictitious, but at the same time, there were so many reasons it didn't feel right to tell other people's stories as their therapist or former therapist to just reveal their actual life stories.

Melanie Avalon: So, was your first client in a hospital situation?

Charlotte Fox Weber: My first client, it still feels so incredibly vivid and real to me, because it was and she was. But again, I've changed just enough details with that one to still protect her confidentiality, even though she's no longer alive.

Melanie Avalon: What made you decide to be a psychotherapist in the first place?

Charlotte Fox Weber: So, that question has always evoked strong, weird feelings in me, because I feel different things at different times. I feel like, "Uh-oh, I should say the right thing. I should say to help other people, because I'm really curious." There are so many reasons I tried-- Not tried. So many reasons I was always interested in therapy. But the real reason is because I have been conflicted about therapy itself since I had it as a six-year-old, I had a terrible experience of being forced into therapy with someone I didn't connect with, felt judged by. It was so unhelpful to me that it was pretty much traumatic. I think it's that-- Maybe it's like a revenge fantasy in some-- Again, all the things I shouldn't be saying, because it's not just about that, but there's definitely a darkness to it that I grew up feeling a kind of determination to correct or repair what had gone wrong in my experience. I wanted to do the opposite of this man and how he was as a therapist.

Melanie Avalon: Wow. How long were you in those sessions with him?

Charlotte Fox Weber: How long was I in therapy jail? I was forced to see him for close to two years by loving, well-meaning parents have to say.

Melanie Avalon: Wow. Did you continue therapy after that?

Charlotte Fox Weber: I did. One of the reasons I had therapy from such a young age was because I'd had heart surgery as a five-year-old and four-and-a-half-year-old. I felt a lot of death anxiety. So, my parents wanted me to feel less anxious. But my understanding of that was, "Uh-oh, my anxiety has gotten me in trouble. I've now been sentenced to have to sit with this person and miss out on other things because of my feelings." I would sit in these sessions and not say anything, and he would stare at me and not say anything. I know you asked if I went on to have other experiences of therapy, but I'm still obviously hung up on this one.

I told him that I didn't want to continue therapy. And the more I resisted, the more I was told that I needed therapy. Like, it was a sign that I needed therapy, the fact that I didn't want to be there. I just couldn't stand him. I would sometimes spend an entire session just spelling out one word, and then he would report the word back to my parents, and I would feel like I'd gotten busted for the one thing I'd said. It was a very unsafe, weird space. But my parents said to me when I was protesting-- I had a tantrum one day and said, "I don't want to go anymore. I really don't like going. Please don't make me go." I remember them both saying it together and being completely united in this, and they both said, "You can say anything you want to him. It's your space to just say anything." And I said, "I can say anything I want?" Somehow, I hadn't realized that and it was utterly exhilarating.

So, I got very excited for the next session. I was in the waiting room of the clinic where I would see him. This story makes me seem totally nutty, I realize. But this therapist came to collect me and I said, "Hello, pig face." I felt something incredibly powerful. In a way, I think that's where therapy can be transformative. Not that you have to call your therapist, pig face, ever, but saying something that feels really difficult to say and that you're maybe not supposed to say anywhere else and going there and saying the unsaid thing, and I think that's when something shifted.

Melanie Avalon: Wow, that's really powerful. That really resonates with me, because I think, for me, one thing I love about therapy and I actually wanted to ask you this and you talk about this in the book. Like the view of the ego, I'm always haunted by the ego and not being selfish and all of that. And so, just talking about yourself from my perspective always feels selfish. And so, in therapy, I'm like, "Okay, this is the one place where it's okay for me to just literally talk about myself [laughs] for an hour." And then also, like you said, it is this sacred space where you can literally say all these things that you can't say to anybody else. My therapist is the one person who knows all the things.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Yes. Actually, I didn't say that thing last week. I lied to you last week. I didn't tell you that I was really hungover in our session or whatever it is. You can sometimes admit that you faked something even in therapy.

Melanie Avalon: One of the things you talk about in the book is the role of power and how it's really confusing wanting power and then what's the difference. This blew my mind. I never thought about this. The difference between power and self-empowerment and wanting power is not okay society wise and we judge it. But self-empowerment is amazing and that's what we're supposed to want. I'm like, "Why is that? [laughs] How are those different?"

Charlotte Fox Weber: I feel like we're going all over the place, and at the same time, there is a definite theme that threads the different topics together in our discussion already around admitting whatever is really going on. Ego and power and empowerment, we're not supposed to really acknowledge whatever it is we want. Especially, I think, to make a generalization, especially as women, we're supposed to not seem greedy in every way, whether that's work wise or wanting something too much or being desperate. Even in our own minds, it's hard to acknowledge what it is you seek, even though it's definitely possible and completely worthwhile. But I think with self-empowerment or just empowerment versus power in my research on this subject, I became really annoyed with-- I love female empowerment. I love empowerment, but I became really annoyed that there's no space for talking about wanting actual power.

There might be exceptions to that in the corporate world, but it's still a little bit vulgar or aggressive seeming to admit out loud that you want power. I don't know how you feel if you'd agree with that, like, saying to someone or even saying to yourself in a friendship. For example, I want power over this person or I want more power in the workplace.

Melanie Avalon: I agree completely. I guess, it's a really-- because now I'm just thinking about it more intensely in the moment, that example of in comparison to another person in a relationship saying you want power over them versus saying you are empowered. Either way, you have power. But I guess, one is about you and one is about what you're doing to the other person?

Charlotte Fox Weber: Yes. By the way, I'm not saying that having power over another person is a good thing, because power has a darkness to it and it's not entirely moral, which makes empowerment a lot less threatening. If someone is empowered, it's more modest. It's just about their own life and they can quietly reclaim the self-respect, and dignity, and esteem, and feel good about their lives. But there is something about power over others or having an impact on others, I think still should be allowed, it still should be explored, even if it's not acted on. But why is it that you want power over this other person? It doesn't mean that you have to act it out in your life, but I think it's really helpful when we can actually confront ourselves in these ways.

Melanie Avalon: I was thinking about this before as well. Why certain wants and desires are seen as good or okay or neutral or bad, and why others aren't. Even in the power situation, there're shades of gray with power. So, there could be somebody who has a lot of "power," but the power is, they're doing good things and the people trust them more like a guru type situation compared to on the flipside and by the guru, not one that goes crazy cult documentary route, but doing good things.

Charlotte Fox Weber: But in subtler ways, yes. Wonderful people who are effective, but still are powerful in complicated ways.

Melanie Avalon: Exactly. And then you can have somebody on the flip side like a dictator situation where it's very, very bad. So, as far as defining what's good and what's bad with these different ones and in this situation, power, do you think it's intuition? We just know if it's "good or bad." Or, do you think it is society telling us what's good and bad? Where do you think that comes from?

Charlotte Fox Weber: When it comes to assessing the good power from the bad power, it is ingrained in us in various ways for how we think about these things for who's entitled to want power when power is allowed, when it isn't. So, if you're playing a sport, you're allowed to want to win. But if you are secretly wanting to feel superior to your friend because you have nicer clothes or you think that you're prettier, that's a different, less acceptable thing to say out loud, but it still can play out in so many hidden ways. I think that we can be on to ourselves when we just admit that we all have shady parts of ourselves and shadowy depths. There's darkness in everyone when it comes to thinking about your actions and your choices.

I think having relationships in your life where you can get a degree of honest feedback is really important for keeping things in check. And that can come from different sources at different moments. But power gets out of control when someone is in an echo chamber and has power over everyone in his or her life and no one can really say how they truly feel about this person's behavior.

Melanie Avalon: When I started it, I was like, "Oh, this is fun." I was like, "I wonder which clients I'm going to most identify with." Really, every single person, there was something I identified with. Some were more strong than others, but it definitely makes you feel not as crazy. There would be examples that you would give from these clients saying something and I was like, "Whoa." I was like, "That's exactly how I feel." So, it's crazy. These things that you think are so secret and unique to you that maybe they're more universal than we realize.

Charlotte Fox Weber: But they can feel outrageous and they can feel very specific and we can feel really alone in our struggles.

Melanie Avalon: Yes, definitely. Just to circle a little bit more on the power thing, is that a common desire or something that you see people struggle with in your clients?

Charlotte Fox Weber: Well, so, I am a little bit provocative about that one, because one of the reasons I identified 12 desires and power was, one, I was particularly excited about was because sometimes, I think therapist is that honest feedback for someone who might otherwise be in an echo chamber or be surrounded by people who are denigrating. It doesn't mean that therapy should be an attacking space. But I think sometimes, I need to provoke someone to acknowledge that actually they do want power in a situation where they're not comfortable facing even the word in themselves, like, even saying it out loud. So, power is a word that I think men-- I am making the gender generalization, so I apologize because there are, of course, exceptions.

Men can talk about power more easily when they have it, not when they don't. Women struggle to admit or acknowledge that they are powerful when they have power, when they want power. It's a hard word to say, especially in the UK where I am. It might better in America. That is certainly the sense that British people often have about Americans. Like, you guys are really comfortable with ego and power. That's something I've heard so many times in England. I don't think that's entirely true either, but I think it's a struggle in every culture to really be comfortable with power.

Melanie Avalon: I find this so fascinating. Yeah, it's so true. Well, it's interesting for me as well. I guess, with any want or desire, there's the want within yourself to have it, and then if you're attracted to it and other people-- I'm trying to think if that would apply to the other ones. But for me, for example-- This is hard for me to say and I think it speaks to the societal judgment.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Oh, then please say it.

Melanie Avalon: [giggles] As far as being attracted romantically to people, the thing I'm really attracted to, I guess, I would say is like achievements or drive. So, I'm very much attracted to people at the top of their game.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Powerful people.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, so, it's so funny-- This is so funny. So, I was telling a friend recently about somebody I was very attracted to and then they're like, "Oh, so, you're just attracted to power." And I was like, "Wait, no, I'm not attracted to power." I was like--

Charlotte Fox Weber: Yeah, it sounds wrong.

Melanie Avalon: I was really thinking about it. I was like, "Am I attracted to power?" I was like, "Is that what I'm attracted to?" Because then I was thinking like, "Well, I'm not attracted really to--" If somebody's like a politician, it's not that.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Not like the power suit necessarily. It's your own bespoke idiosyncratic version. Power means something different to everyone. Each desire that I describe has its own specific meaning. I think that is an important thing to honor in ourselves. Sometimes, we're attracted to people who are powerful in some ways, but actually we also like their weak side. So, we can also be really contradictory in what draws us to someone. I don't know if the people you're attracted to also have a vulnerability that appeals to you, if they end up being monstrous or there're so many questions I could ask.

Melanie Avalon: It's so interesting, because that attraction that I have is the same attraction, but it's like, if I call it something else, then it feels okay to me.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Right. Repackage it as effective.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. If I call it like, no, people who are doing a lot of things in their sphere and are making an impact, I can say high achievers. That's sort of okay.

Charlotte Fox Weber: High achievers sounds much more acceptable than "I like powerful people." But also, is it because you can then have some of that power, will it make you more powerful? Will they allow you to have power?

Melanie Avalon: That's another something I've thought a lot about and something you talk about in the book, which was this idea of, can you win in life and succeed without others losing or if others win and succeed? Some people will feel really threatened by that. Yeah, is that a loss to you? So, it's contradictory though, because there's that concept, but then there's also this concept of wanting to be surrounded by powerful, successful friends. I often wonder having successful or powerful friends, do some people want that and enjoy that, or some people are they always threatened by that? I'm really fascinated by that.

Charlotte Fox Weber: It's usually full of ambivalence and mixed messages. You can be drawn to someone powerful and then end up feeling very powerless. It can go in a lot of different ways, which is why I think paying attention to power in yourself and thinking about it in others is an ongoing process, because there can be rivalries that sneak up on you, where suddenly you realize that you're not wishing someone well or you're feeling weirdly pissed off that your friend has just gotten a major great thing. Like, why is someone's success bothering you? I don't know if that ever happens to you, where you just feel weirdly bothered, but you should be feeling happy and excited for this person.

I think we're constantly assessing ourselves, unfortunately, in relation to other people. It's a kind of one up, one down sense a lot of the time. I think when we cultivate a strong understanding of those factors and we have a clearer picture of ourselves, then we don't need to feel as precarious about these issues. Your surroundings don't have to determine your worth to such an extent, I think if I were to say what the goal of therapy often is really about, it's something to do with that.

Melanie Avalon: I love that so much. So, with this recent situation with a powerful person that I was alert by my therapist. First of all, I love my therapist because she's so supportive and safe and nonjudgmental. So, anything I want to do in my life, she's supportive of it. But the theme, she would keep going with that situation. And it ties into what you just said about not letting the environment determine your sense of wellbeing. She would say, "Remember your own agency in this situation, and you're doing this because you want to. It's not about the power of the other person," which goes back to this idea of the self-empowerment versus the empowerment. On the social side of things though, the social threats, I think what a lot of people-- Because we'll think about evolutionary needs like food, shelter, and sex, basically. I guess, those are the three. But there's the social aspect and from an evolutionary perspective, the social aspect is actually the biggest threat to an animal or our evolutionary ancestors' wellbeing and safety, because you could survive a while without food, you can survive without sex, you can survive a little bit without shelter, but if you get kicked out of the tribe, you're gone. Like, you're dead. So, this intense need for social acceptance and alignment, I think is a huge evolutionary drive that, I'm on in a soapbox, but I feel like people, we look down at it as a shallow want to be socially accepted, but there's like a--

Charlotte Fox Weber: Want to belong.

Melanie Avalon: Yes. I loved the chapter on belonging. To go down that route, because you talk about how with wanting to belong, never to assume that you know where people want to belong and never tell people where to belong. Do you find with your clients that most people do know where they want to belong or where's the spectrum of wanting to belong?

Charlotte Fox Weber: I think it's one of those things that can go in surprising or it should be surprising, can go in surprising directions. So, you could be in therapy for years, and then realize that actually you have been holding on to a wound emotionally from feeling that you didn't belong in your family, feeling that you didn't belong at a social situation like at a school. In so many ways, we have invisible circles where we are in or we're out or we don't know if we should want to be in or out. I think that belonging is a really fascinating desire. At the same time, there's so much social programming where we think we're supposed to want to belong, if that makes sense. We're assigned these roles. We should belong to the workplace, we should belong to motherhood, friendship groups like whatever it is.

It's mapped out in a way that very often is at odds from how we feel. I feel like more of an outsider. Sometimes with certain relatives, I feel much more foreign and alienated and disconnected and misunderstood on different planets with blood relatives than with someone who's from a completely different culture and background where we don't necessarily belong to the same group of genetically connected people, but there's more of a sense of emotional belonging.

Melanie Avalon: The belonging chapter that you had in the book with Dwight, you went into the role of race and worldview.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Which I was terrified of doing, by the way.

Melanie Avalon: It even came across in that chapter about concern. So, for listeners, in the chapter, she has this client, Dwight, who was an African-American former football player having issues with his wife. It took you a while to even-- Because he wasn't bringing up race, right?

Charlotte Fox Weber: So, he wasn't bringing up race. There is a really strong movement in this country. I don't want to be boring talking about another country than when your listeners are in, but there's a very strong movement, I think, also in America for therapists to name the race issue, like to bring it up with a client to acknowledge otherness, and not be colorblind, and oblivious. At the same time, it's a really delicate problem or dilemma anyway, because sometimes, a black person can go to therapy with a white therapist and not want to talk about being black and sitting across the room from a white therapist. That may not be the most pressing issue for that person. A white therapist insisting on bringing up race can be really imposing and annoying.

I think in a way, there's going to have to be clumsiness one way or another when it comes to discussing race in therapy. There should be clumsiness, like, thoughtful clumsiness. But not bringing it up and being the frozen-- I've worked with black people where I have just not brought it up and I felt worried about saying the wrong thing, and I think was a missed opportunity in some of those instances. At the same time, if I just go about any session with a black person by saying, how is it for you to be black and sit across the room from me as a white woman, that's already too directive for the conversation. So, I think it usually is a topic that comes up at unexpected moments and with the acknowledgment that it's not going to be totally comfortable.

Melanie Avalon: You talk about how you'll never be able to understand worldview wise some things that people of other races experience. I guess, there's probably not a yes or no answer to this. But in therapist patient relationship, it's beneficial that people are more similar worldviews or more different worldviews?

Charlotte Fox Weber: I think that difference and sameness is a lot more symbolic than how we script it a lot of the time. I've worked with plenty of people who are from my background, who are the same ethnicity, even the same culture. I can then end up over relating or there can be an assumption of sameness when actually there are differences. I have just written about my own experience of a very traumatic, sexually violent relationship I had when I was young with an older, powerful person. I'm aware that people who have been in therapy with me, a lot of them have experiences of sexual trauma and still there are differences. It's never exactly the same whatever the common ground may be.

So, there will always be a space between-- I think it's important to have that humility in a way as a therapist that even if you have similar worldviews, that doesn't mean that you know exactly what it's like to be this other person. But you can acknowledge that and you can try to understand. So, I describe in my final chapter about control. I describe a man who was anticipating his wife's death and agonizing over it. I felt so, so close to him, and yet, I also wasn't having his experience. We had shared values in certain ways and shared attitudes and characteristics, and there was great rapport, but there's also that gap that I think is just part of any human life where I couldn't fully relate to what he was going through.

Melanie Avalon: He was the one-- I guess, if it's a mosaic anyway, it might not matter if it was specifically him, but was he the one where you weren't originally going to work with him ongoing?

Charlotte Fox Weber: Yes. Well, the first and the last clients time came into it in all sorts of ways, so it was going to be time limited. Yeah, what you set out to do-- If you start by saying you just want six sessions and then it turns into six years, it's always interesting to think about time and desire.

Melanie Avalon: I loved that chapter, especially the control aspect. I'm fascinated by planning and I hadn't really thought about this until I read that chapter actually, because I am such a planner.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Are you?

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. Everything is planned. That's what makes me feel free, is having plans.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Oh, interesting. Because some people feel trapped and some people feel free.

Melanie Avalon: I was thinking of that. I was like, "Why is that?" Like, "Why do some people planning is what makes them feel free and in control and then some people with planning that they feel controlled?"

Charlotte Fox Weber: Right.

Melanie Avalon: Why?

Charlotte Fox Weber: So, fascinated that planning makes you feel free. Do you feel like you're in charge of those plans? Do you make the plans or are they other people's suggestions?

Melanie Avalon: I plan out everything and then they could be other people's plans. But if they're other people's plans, it's me accepting the plan and adding it to my plan. So, I'm still--

Charlotte Fox Weber: So, you're still appropriating.

Melanie Avalon: Mm-hmm. I won't agree. That's something I've had to work on a lot. [laughs] It's like saying yes versus no to things.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Right. The two hardest words in the English language are yes and no. They're so complicated. And then even the movement kind of "say no to more things," it's often subtle. We have mixed feelings about what we're saying no to, or we can start saying no too many things. I think it's just so important to really pay attention to why you're saying yes or no to something, just starting with that basic question. I think when it comes to you and plans and freedom, it sounds like you have a sense of being able to design your life and choose your path and know what's coming next.

Melanie Avalon: Mm-hmm. What's interesting about it, because I think you even commented on this in the book, we don't actually control anything. Well, we think we are in control, but we can't determine how things go. So, maybe it's a little bit of a--

Charlotte Fox Weber: A farce.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, I love that word, by the way.

Charlotte Fox Weber: You love the word, farce?

Melanie Avalon: Yes.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Oh, I like that. I've never thought about it.

Melanie Avalon: I always say, like, "such a farce" is like one of my favorite phrases. But then again, I think with planning, I don't know how I'd be doing my life and everything that I'm doing right now if I didn't hardcore plan everything. So, it does feel effective.

Charlotte Fox Weber: I think that education should teach us how to think about scheduling and planning so much more. I don't think it's in the curriculum unless it's incidental. It would be the most useful class to have every year pretty much throughout school to think about the choices you make when it comes to plans. Like, even as a seven-year-old, eight-year-old, the plan that you have with your friend, that you arrange through your parents, what is it for, what is it about? Not obsessing over it. But even when it comes to scheduling therapy sessions, plans are a really significant part of life. Life doesn't always cooperate with our plans. We make plans and then unexpected things occur. If we don't make plans--

A lot of people who are petrified of committing to plans and don't want to be locked into something and refuse to plan, there's deprivation that comes with that. It's hardly freedom if you've refused to plan anything for your birthday, for example. That happens all the time. I've done this myself. If you don't make a plan and won't make a plan, it doesn't feel so great and in control when you're then disappointed, because you do things that you don't want to do that day or you do nothing at all. We're actually hoping that something magical would occur. We have to be able to make plans and also be able to change them.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. Two comments. One, I dated a guy for a while and he could not make plans. He would literally say to me--

Charlotte Fox Weber: Terribly hard on you.

Melanie Avalon: He would say that he could not, that he did not have the skill or the capability. Like, he tried, he just can't.

Charlotte Fox Weber: That's learned helplessness.

Melanie Avalon: I was like, "I don't know that that's accurate." I'm pretty sure. [laughs]

Charlotte Fox Weber: That's passive aggressive sounding to me. But also, something suited him to have that policy, even if it backfired. Yeah, there's a lot that could be explored with that idea. But in any case, did it make you freak out that he refused to make plans or did it allow you to boss him around? What happened?

Melanie Avalon: On a superficial level, it worked fine because he didn't mind me making all the plans, because then I was stressed because I knew he actively didn't like plans. So, then I was stressed that he would be annoyed by me planning things, but he was fine with it. So, on a surface level, it actually worked really well.

Charlotte Fox Weber: It's a bit of both of you.

Melanie Avalon: The issue was he just couldn't show up for plans. So, then that was the issue. Not so much the creating the plans to that point. And also, I wrote down a quote. I have a note about how to have a healthy relationship with time, which was, again this time control chapter. And you said, "Be reliable with it and discerning how you spend it." And so, I love that. So, basically, this idea of being reliable. So, I think showing up for other people, making plans, honoring commitments, I think is so important.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Tell me you're not in a relationship with this guy still.

Melanie Avalon: Oh, no, I'm not.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Referred to him in the past. Hopefully, he isn't listening to this. But this is where I would be very opinionated and am very opinionated as a therapist, which, I mean, I allow space and support whatever choices a client makes, but I also would voice concern about what you've just described, because that is a maddening dynamic. Setting you up to be the planner and then not only refusing to talk about the plans, but not showing up, it is a recipe for making you potentially anxious and obsessive and demanding. I don't know if it activated those things in you, but if you refuse to make a plan, then how does anything happen.

Melanie Avalon: I'm going back to the control thing. I know I have a lot of control. I don't know if it's control issues. Like, I'm very controlling with my own life, but I actively do not ever want to control other people. Because I used to be really bossy when I was growing up I think, because I am very controlling. I remember, I think in middle school maybe, my best friend at the time told me I was bossy.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Oh, one of those words.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. And after that, I like, "Oh." I was like, "I cannot be like this." So, actively since middle school, I've been like, "Do not be bossy. Do not control other people." So, I'm so glad she told me that. It's crazy how one person can say one thing at one moment, it can have such an impact on your life.

Charlotte Fox Weber: It's such an impact. That is why each of us has idiosyncratic relationship with different desires for what it means. It could be something you watched on TV, something a teacher said a moment in time that ends up being formative for how you think about yourself and an issue. But I also think that you're allowed to revise and update your relationship with that desire. So, I'm wanting to push you, I mean, I'm just admitting this out loud. You can tell me to shush, of course, but I'm wanting to push you to allow that you might still want to control people occasionally, even if you don't. Even if you aren't controlling the desire to control another person, it certainly seems to come into a lot of people's minds more often than we end up admitting to.

Melanie Avalon: Well, what it's like is-- I don't know. Do you listen to Taylor Swift ever?

Charlotte Fox Weber: I love Taylor Swift.

Melanie Avalon: Oh, good. [laughs] Okay. Well, she has her song, Mastermind on her Midnight's album, which is basically this idea of her in a relationship being the mastermind and planning.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Yeah, this is why I love her, because she's so bold and she says the things that are kind of taboo that we don't want to admit, but she says it and it's liberating.

Melanie Avalon: So, that song has resonated with me, because like you just said to me, so actively, I don't think if you met anybody that knows me-- I don't want to speak for other people, but I'm pretty sure you could walk up to anybody who knows me and they would say, I'm not controlling. That would not--

Charlotte Fox Weber: Controlling. Right.

Melanie Avalon: But going back to what you just said about wanting control of other people, maybe I try to come up with the perfect plan to get what I want from somebody without them feeling like it was me controlling the situation.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Right. I think the great thing about therapy and connection, in general, it can come from different sources, is radically accepting that we can have all sorts of longings and desires and fantasies and thoughts. They're not all nice by any means. But there's a world of difference between what we think and feel and how we behave. So, I worked with someone recently who was shocked to realize that she absolutely wanted to control her father. She wasn't behaving in a controlling way. She was actually behaving in an overly compliant way, but she was incredibly upset by a situation. That was really the kind of crux of it in a way that she didn't want to feel, didn't want to want, but she wanted to control him and tell him to do something and fix him and maneuver him. It's not as if she then went on to do those things with her father, but facing it in herself allowed her to forgive herself for wanting to control someone and realize that she couldn't and didn't have to be controlling.

Melanie Avalon: Okay, that's such a good-- because there was a really similar mirror situation I had reading your book, The Attention chapter, when you're talking about wanting attention, you gave an example of people wanting attention. Often, it's like showy, like people doing all this stuff to want attention, but also it can be the opposite. It can be not being present to give attention. So, I was like, "Oh." So, for example, me not texting somebody, that's allowed, but that's actually me still trying to get attention. It's the same want.

Charlotte Fox Weber: But we're covert. We're very cloak and dagger with how our desires play out. There're so many sneaky, hidden, camouflaged ways of expressing ourselves. And again, when we can be onto that and just recognize what it is that we're really doing whatever is really going on, then there can be a kind of congruence, but I'm going to fixate over this now probably. But the guy you described who refused to make plans and then didn't show up, that is a very impactful position to take. It is a plan in itself. The refusal to make a plan, that's actually a lot of work already that he's set up. And whatever plan you were making and then waiting for and then would he show up or would he not show up, that's so present.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, it was like planning for me to fly to see him and then being stood up-type situations. [laughs] It was not good.

Charlotte Fox Weber: That's just actually terribly rude and not acceptable as behavior, but also, it's making him utterly significant. One of the things I've noticed is, when people are-- I can be guilty of this, definitely, but when people are really chaotic and unclear about their plan, like will they be there? When are they coming? Do you know when your friend is going to be there? Is she going to the wedding or not? Will they arrive or not? You can be sitting at a party dominated by the person who might show up, but might not show up. It's an impactful move to be unreliable and to be avoidant in those ways.

Melanie Avalon: No, I'm feeling it viscerally on my body. It's very impactful. I remember one time, just not to give a specific, but we were driving to see each other, both of us driving four hours to see each other, and we were texting the whole way. So, clearly, it was going to happen. I was going to meet him. I was texting him. And then after driving four hours, he stopped responding. He had so been that way throughout the whole relationship of not showing up or maybe showing up or changing plans that I was like, "Okay, he's not showing up." He did show up. But the fact that I had that feeling of not getting a text after driving for four hours, I was like, "Okay, it's a good mirror for me to realize the effect it has had on me as far as how it's controlling me and the relationship" or I'm letting myself be controlled.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Right. It's hugely labor intensive, what you've just described. The amount of emotional labor that goes into wondering if someone will come or not, it's so stressful and it's so preoccupying. Then you're trying not to seem worried and be annoying and demanding and controlling. Oh, you're doing things acrobatically in your own mind trying to accommodate someone who could just actually make things simpler and clearer. I think when it comes to plans, we can all be tricky as well. No one is perfect about plans. If you're perfect about plans, then that in itself is problematic. But we all have uneasy, interesting relationship with plans and time.

Melanie Avalon: Huge question from that, because first of all, I will say, so that relationship was-- I have nothing but gratitude for what it was and what I learned and what I experienced and what I learned from it for going forward. It was really bad at points.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Interesting, because [laughs] I'm feeling darker things just hearing about it.

Melanie Avalon: No, it was very, very dark. Actually, it's like one of your clients talking about regrets. I don't really have regrets, because I had beautiful moments and I learned so much from it. And going forward, I learned what to appreciate more, I learned what to look for, which this goes to a huge question I have as far as the concept of red flags and yellow flags and-

Charlotte Fox Weber: Beige flags.

Melanie Avalon: [laughs] -other flags. So, after that experience with that person, I created a rule in my head where I was like-- This wasn't for necessarily romantic. This was just for engaging with anybody. I was like, "If I make plans with some--" because I'm always doing calls with people, because I'm meeting people constantly. So, I was like, "I'm going to have a rule where if I'm making a plan to meet somebody for the first time like for a phone call or something, and they stand me up, like, no second chances, unless they got in an accident or something."

Charlotte Fox Weber: So glad that I did not mess up in our meeting.

Melanie Avalon: Oh, no.

Charlotte Fox Weber: I like it. It's hardcore.

Melanie Avalon: Well, that's my question though, because at first, I was like, "Okay, this is my rule." Like, "No second chances, unless it's something where obviously it makes sense." They got sick or if it's just a no show.

Charlotte Fox Weber: It better be a good excuse.

Melanie Avalon: Mm-hmm. Yeah, but then I was like, "Is that a healthy approach to take?"

Charlotte Fox Weber: I think if someone stands you up and isn't in touch and actually sorry about it, then that's not considerate behavior and believe people when they show you who they are. So, I think it's an understandable protective measure that you took after the no planner guy to not be messed around again. When we're traumatized by a relationship or by something, there is a very strong, healthy desire to make sure that never happens again. But at the same time, we can work against ourselves, and weirdly repeat, and reenact different versions of it happening again and again.

Melanie Avalon: The takeaway I took from it was, for me to not show up for something, I have to be like dead or-- I will at least let you know. If I got in a car accident, the first thing I probably-- If I was meeting somebody, I'd be like, "Okay, tell this person." What it says to me is whether or not you value somebody else's time.

Charlotte Fox Weber: And respect. I think respect is such a huge part of plans and time.

Melanie Avalon: Something else that you touched on not wanting to want things or wanting to want things. I'm really fascinated by this concept of-- You talked in the book about how we don't like the feeling of desperation and we don't like the feeling-- Yeah, well, really of desperation, of wanting something so bad that we don't like that feeling. I had that experience recently and I was actually thinking about your book when it happened, because I found myself--

Charlotte Fox Weber: Because we all have moments of desperation, by the way.

Melanie Avalon: Little parts of things from your book pop into my head now when I experience different wants and desires in life. So, I found myself in a situation where I was really wanting another person, and I hadn't had that experience in a while. The thing I was saying out loud on repeat to my girlfriend that I was with was, I don't like this-- Again, I had a lot of wine in me though too, but I just kept saying in repeat, I was like, "I don't like this feeling. I don't like this feeling."

Charlotte Fox Weber: It's out of control for one thing. If you like control--

Melanie Avalon: So, what do you find with people with the wants and the secret desires that they have and enjoying that want versus not wanting to want things? You even had one client who didn't want to care about things. That was the Freedom chapter.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Yes. You're so retentive. I feel so read by you.

Melanie Avalon: It was very, very engaging work. So, how do you feel about this concept of wanting things, wanting to want things, not wanting to want things, feeling free if you want or don't want something, attachments? What are your thoughts in that world?

Charlotte Fox Weber: I think that we should lean into the discomfort of wanting and not having and having some of it, not all of it, potentially losing it. Desperation and helplessness happen to all of us. Whether we want it to or not, there are desperate moments in life. I think that if we can tolerate that and surrender to that, that is not the same thing as completely collapsing and just giving up. But facing the really helpless, delicate part of ourselves and being strong about the delicacy, I think we can be more comfortable with the discomfort if that sounds possible. Like, you can breathe more easily when you realize that actually. Of course, you're going to have feelings of desperation and terror and out of controlness being sexually attracted to someone, romantically infatuated by someone who might not like you back or who might like you back, but might mess you around or might even make you happy, that too can be overwhelming.

But there are all sorts of risks involved in feeling desperation or admitting desperation to ourselves or to someone else. But it doesn't make you a desperate person. I think what you said at the beginning of our conversation that not feeling judged by a therapist is really the most important thing. Part of that I agree with you and part of that is because we are so harshly judgmental of our own minds and working against that. Even the bossy remark, I want you to lean into that and embrace and love the bossy side of you. It's all part of you and it's all acceptable. Like, feeling desperate, feeling powerful, feeling free, feeling trapped, whatever it is, you can actually survive it. So, I think not being freaked out and intimidated by our own minds is a big part of what helps us deal with desire itself.

Melanie Avalon: I'm so glad you said all of that. That's definitely been a theme in my own therapy sessions, which is-- It goes back to what I was talking earlier about being haunted by this concept of the ego. I'll talk with my therapist about different parts of me. She does give me that perspective that you're giving right now of loving and accepting these parts of myself that I very severely judge. When she first was saying that, I was putting up a lot of resistance and barriers to it. I was raised really religious. I have these ideas of thinking, "No, this is wrong. These things are definitely wrong. This is bad. This is good." And so, it's really hard for me to not judge and not feel guilty about a lot of stuff.

Charlotte Fox Weber: That's so honest and real. You've been socialized to evaluate your character in these ways and undoing that. Like, even the pressure to not be judgmental about yourself, it's really hard and it doesn't just happen instantly.

Melanie Avalon: Oh, which actually, this ties back into something I wanted to talk about earlier, so this brings it all together. Going back to the concept of-- well, it's a lot of concepts that we've touched on. But power and also women in society. There was one client who I think it was your longest client, and she was talking about how-- She was haunted by her youth and her beauty when she was younger. She was talking about how--

Charlotte Fox Weber: The Attention chapter.

Melanie Avalon: Wait, was it Chloe or Astrid? I think it was Astrid.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Or, was it wanting what you shouldn't? Alice.

Melanie Avalon: Alice. Yes, it was Alice.

Charlotte Fox Weber: The one who becomes healthy, but misses the self-destruction.

Melanie Avalon: Yes. So, she talks about this idea that-- She said that she would pretend to be more critical and doubting than she was, because she was saying that she couldn't be pretty intelligent and fun all at once. She couldn't be that. [laughs] So, she would dumb herself down. Or, if she had something like with her abuse situation, then it was okay for her to beautiful. She was basically saying that, in society, you can beautiful if you're broken, but you can't beautiful in all these other great things and not have issues, then you're, I guess, a threat to society. What do you feel about this idea of women in society and how it's not okay to be--? Like I just said, you can't be powerful and beautiful and intelligent and all these things. That's not okay or you judge yourself for it.

Charlotte Fox Weber: It's not okay. I think it is okay, but yes, we are told in so many ways that it's not okay. We're given mixed messages. So, on the one hand, love yourself, respect yourself, empower yourself, even have gratitude. But on the other hand, don't be full of yourself, don't be greedy, don't be demanding, don't be needy, don't be bossy. There are so invisible injunctions like rulebooks that we're carrying around in our heads that come from different voices of authority, and systems, and cultures, and religions, and family values, and friend groups. We get really judgmental about actually liking ourselves. It can be weirdly difficult and totally worthwhile to let yourself enjoy the moments of really liking yourself, liking how you look, liking how you sound, liking something you've achieved, liking just how you feel, whatever it is.

I think we need to encourage ourselves and each other to just really be okay with that. But we're stop starting a lot when it comes to ego, because there is some ego in that. Ego is not the same as narcissism. Ego is sense of self and individuality. And yes, it can be out of control, but so can everything. I think it's a really unreasonable and punishing message that we should have no ego. Get rid of the ego. We say it a lot of the time-- I used to say it or hear myself saying it years ago like, "No. That's egoey. I don't want ego. It was a dirty word." If we allow that we have ego, then it's a healthy thing that can be worked with. It doesn't have to make you a dictator or make you unbearably arrogant, but pretending to have no ego or really diminishing yourself and feeling diminished to the point of not thinking you matter, it can make your life just so miserable.

Melanie Avalon: Like I said earlier, I'm haunted by this idea of the ego. And like you said, we make it a synonym for narcissism.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Like bad. Basically, just bad.

Melanie Avalon: Mm-hmm. Yeah. Where you could have, I guess, a more appropriate synonym for the ego or maybe would be just the authentic self like this is--

Charlotte Fox Weber: Yeah, I love ego because it's just three letters. And ego is my amigo. [laughs] It's one thing I like to think of. It's so simple. Yeah, you could find a replacement if ego is tarnished as a word. But I think part of the problem with the word itself is that it has so many different meanings and definitions and interpretations, like, even just historically, for what it means. But a sense of your own worth that we are worthwhile, and even more than worthwhile, we can be fond of ourselves. We can enjoy our own company. We can really like something that we've done or something about who we are. So, I think that desire comes into all of that, because if you don't consider your own desires, then you can't really have a picture of who you are.

Melanie Avalon: I read a quote and it was saying that, "The way that we should view ourselves is basically like we're a picture that somebody else painted." For self-love, like, "Appreciating something that we didn't create." There's no "ego" in really appreciating a picture that somebody else drew. But if you drew it, then it's like, "Oh, then it feels egotistical." So, it's like, if we could have that perspective, just a third-party objective.

Charlotte Fox Weber: If you could see yourself through rose tinted glasses.

Melanie Avalon: Yes. Or as another person appreciating yourself.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Or even just through clear eyes, like, just seeing yourself with enough air to have an actual viewpoint. But I think we get so locked into our own heads that there's this great expression, the eye cannot see its own eyelashes unless you get eyelash extensions, which I'm in favor of if you want to. But it's hard to see your own eyelashes. If you try it right now, in this moment, you can't really see them. You can't really see yourself in your own wonderfulness or difficulties with absolute perspective. I think that it's important to not think that you can really, really know exactly who you are, because it's not as if you're then able to arrive at ego confirmed and then that's it. It's an ongoing process and it's an interesting, curious, playful, adventurous process of discovery and change and growth.

I think sometimes just knowing that we can't yet see ourselves with clarity is a really big revelation. So, whatever confused and contradictory picture we have of ourselves, we don't really understand exactly how we think about ourselves.

Melanie Avalon: Well, it's so interesting. I remember one of the things my therapist said was, I was judging a part of myself, and we were talking about the ego, she and I.

Charlotte Fox Weber: I'm so glad that she goes there.

Melanie Avalon: Oh, yes. Because like I said, I have to unlearn a lot of what I was taught growing up. One of the main things that was drilled into my head, which did have positives, but I think it also had some negatives, which was like, be modest. That was like don't tempt the men. Humility, I think, is really great, but it was very much like be modest, like, don't draw attention to yourself. But what my therapist was saying was-- I don't remember what it was that I was judging and talking about ego, but she was saying that the part of me that was judging myself, that was actually-- the negative ego was the part of me that was actually trying not to have an ego.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Oh, I like that. Your therapist sounds really good, by the way. She sounds bold, and onto things, and pushes you. Pushes is another word that can sound wrong, even controlling, but nudges, provokes, and you are comfortable with her. But it's so difficult to realize that even your critical side, your complainy side, your helpless side, it can be full of hidden ego agenda. So, being bullied by your boss and committing yourself to that kind of egomaniacal boss, something I have certainly done, there was some part of serving and wanting to please this other person and judging myself, hating myself. There was some part of that that was also my own twisted ego that got misdirected and played out through that relationship if that makes sense. Even though I was diminished and subservient in a way, I was actually secretly wanting to be more powerful and be more like him.

Melanie Avalon: 100%. Actually, I used to have very long esoteric debates with my friends I remember in high school, and it was around the question of, can you do something you don't want to do? Because I remember thinking, I think everything you do is actually what you want to do, even if you think it's what you don't want to do.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Yeah. I think we're usually really ambivalent and have mixed feelings.

Melanie Avalon: With every action.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Well, with every action. I think there are different parts of it. I think that we sleepwalk through a lot of life, unfortunately, and that is the thing to work against. We can go into autopilot where we are doing things, and not thinking about why we're doing them, and not even having feelings or knowing about the feelings. We're in autopilot and we're going through the motions of life without really feeling alive. But I think when we pay attention to why we're doing something or how we feel about something we're doing, usually, it's for mixed reasons. Some part of you wants to do it to please someone else. Some part of you wants to do it for another hidden reason. We're never exactly as we seem. I feel like I'm making us sound surreptitious and tricky, but we are.

Melanie Avalon: Even in the sleepwalking through life situation, it feels like, at that time, that person, what they want is to be on autopilot.

Charlotte Fox Weber: It's not like the ultimate vision of the glorious life to be a sleepwalker, just like going through the motions of going to the same place every day, having the same conversations, doing the same thing again and again and again, and not doing the things that actually interest you.

Melanie Avalon: At that moment, that's what they want. Because if they wanted something more, another option more, then I feel like they would do that. Like I said, I would have this debate for hours with my friends in high school. I don't know how you do something that's not what you want to do. I don't know how that's possible.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Interesting. We could debate for hours on this one. I think that we can do things for reasons that we haven't considered and actually we really didn't want to be there. We really didn't want to do that, but we did want something else, which is how we got into that situation. So, when you find yourself just raging with resentment, I don't know if this happens. I get resentment debt that sneaks up on me where suddenly I've addressed this pattern and I try not to go into resentment debt by acknowledging fast and often when something bothers me.

But if I pretend to be okay with doing something that I'm not actually up for doing and I commit to something that actually doesn't suit me and doesn't serve me and isn't working for me, but I'm still going along with it and giving more and more and more without really wanting to. I think there is this resentment that just festers and it grows. It can be deadening and de-spiriting and it can play out in different ways for us. It might come out as rage. It might come out as lost motivation and apathy and disconnection, but I think that looking at what you're doing in your life that you really don't want to be doing, it's really important to think about it and think about why you're still doing it. Sometimes, we have to do things we don't want to do, like, pay taxes, and go to an event that is just really important, but you really don't feel like going. But I think that understanding why we've made that choice gives us an individuality and honesty in a way, emotional honesty. So, like, "Okay, I'm going to that wedding because it's really important to this relative of mine." But I also know that I'm dreading it, and going begrudgingly, and maybe it'll end up being more fun than I expect it to be, but just actually being unvarnished in our own way of thinking about ourselves.

Melanie Avalon: I love this so much. My sister and I talk about this all the time. We're big proponents of not doing things. Again, there are exceptions where you really do have to go for whatever reason, but basically, not going to things that you don't want to go to just for other people. Like, just don't.

Charlotte Fox Weber: The people pleaser trap, because it tends to not work well for you, sometimes for the other person. Sometimes, when the people pleaser can say yes to too many plans and then disappoint everyone by falling short in some way everywhere, it doesn't necessarily even achieve the goal of pleasing someone when you just go along with something that you don't want to do. I think that clarity is kindness. Actually, if you know that you don't want to do something, it's also not fair to another person to resentfully, dutifully go along with something and not be honest about wishing you were anywhere else. I even include the role of being a therapist with that.

I describe some of the struggles I've had with clients, like, when I'm pissed off with them or feeling frustrated or holding back from saying something. Sometimes, it's really difficult to bear witness to a person who's making damaging choices or thinking about something in a way where I think about it in a different way, my ego is getting in the way or they're denying something. Whatever it is, I think that actually being silent about how you really feel, it comes at a cost.

Melanie Avalon: I agree so much. Two things, one is, you know when you have that urge, I definitely feel it in my body when you feel like you should say something or you're not expressing a want or a need. I don't want to make blanket statements, but I like what you said about clarity is kindness. I just feel like being honest about the situation can be so helpful. And same thing with boundaries. Because I think people often look at bound-- I'm like all about the boundaries. I feel like people see boundaries as selfish that if you have boundaries that that's just thinking about yourself. But I honestly, genuinely believe that.

Charlotte Fox Weber: It's kindness.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. The only way you can really show up to the world and be the best version for yourself and others is, if you have, I think, boundaries in your life.

Charlotte Fox Weber: Because it's that paradox as well that you have to have. You have to have railings in order to then have the freedom to wander. Like, you have to know the parameters in order to then be playful and know what you're in for. I once went to a time management workshop, where the woman running the workshop, she arrived late, which really pissed me off. I was just actually so annoyed.

Melanie Avalon: It's a time management workshop.

Charlotte Fox Weber: She didn't acknowledge the irony. Had she arrived late and admitted that this was an instance of getting it [giggles] wrong with whatever timing thing kept her from being on time. But she acted like she wasn't late, and then was confused, and gaslit the audience. But then she ran over, which again would have been fine had she said that that was the plan, that she would make up for having arrived late by running late. But she ran over by such a huge amount of time that I became really agitated and anxious about then being late to the next thing that I had planned. I found myself trapped in this time management workshop that was meant to help me. It did help me, but not in the way I expected it to.

But boundaries like, say what you mean. I don't want to go on that trip, because I don't want to go there. It can be so helpful for the other person also, rather than pretending to be okay with something, and then acting hostile or weird or mute or having to put on a show and fake how you feel, like, it can actually be such a relief. Just be straightforward. It's efficient as well. It's efficient and you can deal with it whatever it is.

So, one of the clients I describe-- I ended up not including this detail in the final version of the book, but this person asked me if he was boring and he had a fear of being boring, and I pretended to not ever find him boring for quite a while, because saying to someone who's in therapy with you, "Yeah, you're boring." Oh my God, it feels so mean and so horrible and unkind. And yet, he was an interesting person who had become incredibly bored by certain issues in his life. He was bored and he was boring himself. I was pretending not to see what was happening. It wasn't actually fair to him to keep pretending to not be bored by what was boring. So, I finally acknowledged to him in a way that was respectful and not aggressive or a wholesale put down, but I acknowledged that actually the way he was talking about something again and again and again, and the details that he was focusing on were not as interesting as they could be.

Then I did say the word. I'm even awkward about the word right now. I finally said it was a little bit boring, but not as a person overall, like, we're all occasionally boring and we're occasionally aggressive and we're occasionally bossy and occasionally domineering and occasionally clumsy. Whatever it is, we can embrace it without thinking that that is a kind of definitive label on who we are.

Melanie Avalon: How did he respond?

Charlotte Fox Weber: Oh, it was one of the best breakthrough moments. If I sound braggy, it's because I'm really glad that I finally went there. He was incredibly relieved, because he knew he was being boring. He knew he was bored, but then he was trying to convince himself that he wasn't ever boring. He had this fear of a part of himself when actually he could relax about it. I was denying reality in a way. Once I could just acknowledge that something was boring and not deeply fascinating, it was survivable. The work became energetic again. There was something stimulating about it, I think, for both of us. Not in a sexual way, but there was energy and fresh life, because we had just finally clarified. The emotional truth, I know it is a cliche, but the truth does set you free. It doesn't mean that you have to go around telling everyone everything or say absolutely everything or think that you know the only truth, but actually embracing whatever the feeling is, whatever the thought is, and knowing that you can handle it. Desperation definitely is part of that too.

So, when people say, this is a desperate side, I feel desperate, I don't want to be desperate. I will say again in a way that I hope is thoughtful always, but this is desperation. What of it? It's not a shameful thing to feel desperate. It's uncomfortable, it's unpleasant, but it's not something that we have to be horrified by.

Melanie Avalon: That's so interesting as well. That's actually one of my few fears that I do have in therapy. I always am worried that what if they're bored. Actually, the reason I mentioned I said earlier, all of my therapist changes were because I had moved, but the one that wasn't was a therapist I had, and we were doing brainspotting.

Charlotte Fox Weber: EFT.

Melanie Avalon: It wasn't EMDR. It's similar. I think it's called brainspotting, but it's not EMDR.

Charlotte Fox Weber: It might be brainspotting.

Melanie Avalon: I have a company I work with also called BrainTap. So, that's why I'm getting confused. I think it was brainspotting. But in any case, she actually fell asleep during one of our sessions, [giggles] and it was like all of my worst fears about therapy because I have this fear, maybe not so much that I'm boring, but maybe by extension that's what it would be. I have this worry that the therapist doesn't want to be there. Like, they don't want to be listening to my problems right now. Yeah, she fell asleep.

Charlotte Fox Weber: That they won't like you or find you interesting and wonderful.