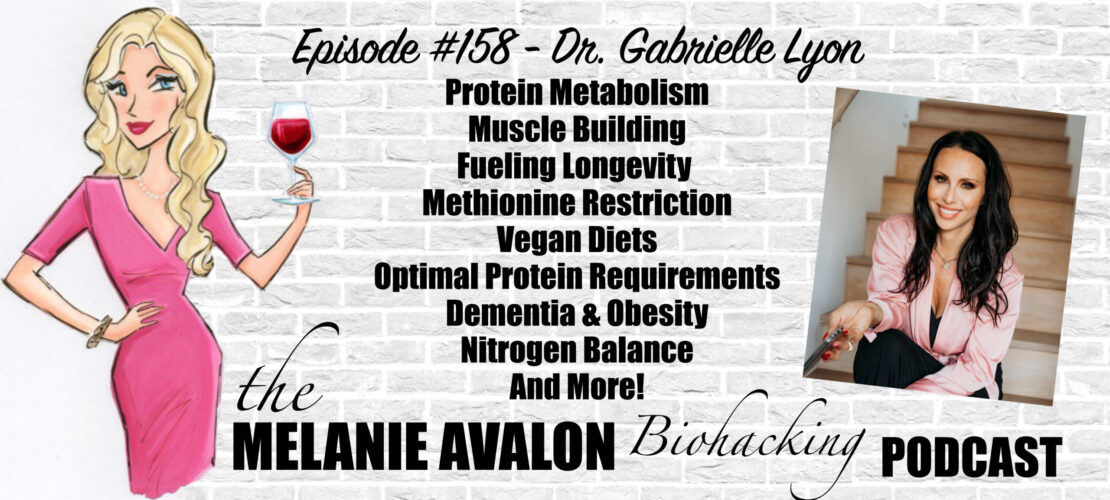

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #158 - Dr. Gabrielle Lyon

Dr. Gabrielle Lyon is a functional medicine physician specializing in the concept of muscle-centric medicine, which focuses on the largest organ in the body, skeletal muscle, as the key to health and longevity. Her individualized wellness plans include interventions using high-quality protein diets, supplements, and resistance training to improve health, reduce chronic disease risk and boost overall energy and wellness by focusing on building and maintaining healthy body composition and lean muscle.

In her private practice, Dr. Lyon leverages evidence-based medicine with emerging cutting-edge science to restore metabolism, balance hormones, and optimize body composition with the goal of lifelong vitality. She treats patients of all walks of life – from sarcopenic individuals that want to improve muscle to age independently to overweight and pre-diabetic adults who need to manage weight and improve lean body mass for better health. Her patients also include elite military operators such as Navy SEAL, CEO, and mavericks in their prospective field who benefit from her whole-body, whole-person approach.

She received her doctorate in osteopathic medicine from the Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine and is board-certified in family medicine. She earned her undergraduate degree in Human Nutrition from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, where she studied vitamin and mineral metabolism, chronic disease prevention and management, and the physiological effects of diet composition. She also completed a research/clinical fellowship in Nutritional Science and Geriatrics at Washington University in St. Louis.

A nationally recognized speaker and media contributor, Dr. Lyon has been a recent guest on The Doctors and has written for Muscle and Fitness, Women’s Health, Men’s Health, and Harper’s Bazaar. Her subject matter expertise ranges from brain and thyroid health to lean body mass support and longevity.

Dr. Lyon sees patients in New York City and resides in NYC with her husband, who recently transitioned out of the Navy SEAL teams, and two children.

LEARN MORE AT:

@drgabriellelyon

drgabriellelyon.com

SHOWNOTES

2:10 - IF Biohackers: Intermittent Fasting + Real Foods + Life: Join Melanie's Facebook Group For A Weekly Episode GIVEAWAY, And To Discuss And Learn About All Things Biohacking! All Conversations Welcome!

2:25 - Follow Melanie On Instagram To See The Latest Moments, Products, And #AllTheThings! @MelanieAvalon

3:00 - AvalonX Magnesium 8: Get Melanie’s Broad Spectrum Complex Featuring 8 Forms Of Magnesium, To Support Stress, Muscle Recovery, Cardiovascular Health, GI Motility, Blood Sugar Control, Mood, Sleep, And More! Tested For Purity & Potency. No Toxic Fillers. Glass Bottle.

AvalonX Supplements Are Free Of Toxic Fillers And Common Allergens (Including Wheat, Rice, Gluten, Dairy, Shellfish, Nuts, Soy, Eggs, And Yeast), Tested To Be Free Of Heavy Metals And Mold, And Triple Tested For Purity And Potency. Order At Avalonx.Us, And Get On The Email List To Stay Up To Date With All The Special Offers And News About Melanie's New Supplements At AvalonX.us/emaillist, And Use The Code MelanieAvalon For 10% On Any Order At Avalonx.us And Mdlogichealth.com!

5:40 - FOOD SENSE GUIDE: Get Melanie's App At Melanieavalon.com/foodsenseguide To Tackle Your Food Sensitivities! Food Sense Includes A Searchable Catalogue Of 300+ Foods, Revealing Their Gluten, FODMAP, Lectin, Histamine, Amine, Glutamate, Oxalate, Salicylate, Sulfite, And Thiol Status. Food Sense Also Includes Compound Overviews, Reactions To Look For, Lists Of Foods High And Low In Them, The Ability To Create Your Own Personal Lists, And More!

6:30 - BEAUTYCOUNTER: Non-Toxic Beauty Products Tested For Heavy Metals, Which Support Skin Health And Look Amazing! Shop At Beautycounter.Com/MelanieAvalon For Something Magical! For Exclusive Offers And Discounts, And More On The Science Of Skincare, Get On Melanie's Private Beautycounter Email List At MelanieAvalon.Com/CleanBeauty! Find Your Perfect Beautycounter Products With Melanie's Quiz: Melanieavalon.Com/Beautycounterquiz

Join Melanie's Facebook Group Clean Beauty And Safe Skincare With Melanie Avalon To Discuss And Learn About All The Things Clean Beauty, Beautycounter And Safe Skincare!

10:20 - Gabrielle's Background

16:20 - the effect of body composition and obesity on brain tissue

18:00 - methionine restriction

20:00 - integrated stress response

21:20 - Vegan Diets and health outcomes

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #134 - Dr. Neal Barnard

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #37 - James Clement

25:10 - full restriction vs cyclical restriction

27:10 - the importance of protein quality

29:30 - nitrogen balance

31:00 - RDA

34:00 - the ratio of protein needed per lean mass

35:40 - basic vs optimal

38:10 - Leucine

40:25 - protein Absorption and digestion

41:15 - multiple meals vs one meal a day

46:10 - muscle maintenance and muscle growth

47:30 - Gluconeogenesis

48:50 - enzymatic adaptation

49:45 - Emscuplt

52:30 - consuming excess protein

53:10 - BUN Creatinine ratio

54:50 - filtration rate

55:00 - LMNT: For Fasting Or Low-Carb Diets Electrolytes Are Key For Relieving Hunger, Cramps, Headaches, Tiredness, And Dizziness. With No Sugar, Artificial Ingredients, Coloring, And Only 2 Grams Of Carbs Per Packet, Try LMNT For Complete And Total Hydration. For A Limited Time Go To drinklmnt.com/melanieavalon To Get A Sample Pack For Only The Price Of Shipping!

57:55 - Are You Burning Fat Or Muscle In A Protein Deficit?

1:00:00 - protein sparing modified fasts

1:00:30 - Myokines

1:04:40 - growth hormone and fasting

1:05:50 - protein intake and longevity

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #115 - Valter Longo, Ph.D.

1:13:35 - protein intake in old age

1:16:15 - protein scores on food labels

1:20:15 - plant based nutrition

TRANSCRIPT

Melanie Avalon: Hi Friends, welcome back to the show. I am so incredibly excited about the conversation that I am about to have. It is with somebody that I have been dying to interview for actually, honestly for years about a topic that I am personally ridiculously obsessed with, and that is muscle and protein. I'm here with Gabrielle, Dr. Gabrielle Lyon and she doesn't know this yet. But my protein intake when I tell people that they are always shocked, and they don't believe me. Because I just think it is so important. And I'm always on the intermittent fasting podcast talking about the importance of protein. So, I'm super aware of the health benefits and I'm excited to dive deep into that.

But then I'm also super haunted because there's all these ideas of protein restriction for longevity. And I've had people on like Dr. Valter Longo and David Sinclair and they're saying, completely the opposite of high protein diet intake. So, ooh, this topic, I have so many questions. I'm so excited. Dr. Lyon, thank you so much for being here.

Gabrielle Lyon: What a great intro. Thank you for having me.

Melanie Avalon: So, I'm sure listeners are probably very familiar with your work. But I'll tell them just a little bit about your background, which by the way, we were just talking offline. We were connected officially through Cynthia Thurlow, which is so fabulous because she's my new co-host of the Intermittent Fasting Podcast. So, it's just a wonderful small little world. But in any case, Dr. Lyon has a doctorate in osteopathic medicine from the Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine. She is board certified in family medicine. Her undergrad was in human nutrition from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. And I love this, where it says, "She studied vitamin and mineral metabolism, chronic disease prevention and management and the physiological effects of diet composition." Oh, my goodness, I'm so-- that's like the rabbit tangent holes on my life every night researching that.

And she's completed a research and clinical fellowship in Nutritional Science and Geriatrics at Washington University in St. Louis. And you've probably seen her, well, you probably seen her on social media and podcasts and all the things, but she's been on The Doctors and written for Muscle & Fitness and Women's Health and Men's Health and ooh, so many things.

So, again, thank you so much for being here. I have so many questions for you. But just to start things off, and to welcome you to our audience here. You're known as-- your focus being the importance of protein and muscle and all of that. Did you have an epiphany one day that led to that? What led to your fascination with that?

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah, you know, it's really interesting. I don't know if you believe in serendipity, but I certainly do and I started my Nutrition. I was really interested in Nutritional Sciences from a very young age. I graduated high school in three and a half years and I moved in with my godmother. And it just so happens that my godmother was a Ph.D. and is a Ph.D. in Nutritional Sciences. This was kind of the generation before Mark Hyman, she would kill me for saying that. She's a little more senior and very well-known and a professor in the medicine space, and also in the Integrative Functional Medicine Space. And her name is Liz Lipski.

And after living with her, so I was working for women board, doing all kinds of things, it really transformed the trajectory of my life, becoming really interested in Nutritional Sciences. And then I went to the University of Illinois, I studied human nutrition. Lo and behold, where I really gravitated was protein metabolism. And I fell into the lab of Dr. Donald Layman, who really is a pioneer. He's a Professor Emeritus now, so he's retired, but he's a pioneer in the nutrition space, especially when it comes to protein metabolism. And in fact, when we get into our discussion a bit more, this whole leucine concept that it's a meal threshold, which is one of the essential amino acids, he discovered that. That was a discovery from him and some of his students. Tracy Anthony was being one of those individuals that discovered that leucine was a meal threshold.

Melanie Avalon: Wow, he's an OG then?

Gabrielle Lyon: He isn't very OG. Yeah, yes. That really became where my interests lay. And then what happened was really fascinating. So, I did not like medical school. I did not like residency. Unfortunately, it was pretty disease-focused. But of course, being able to understand the baseline issues with disease allows you to be a very capable physician.

And as a physician, you spend a lot of time and energy really focused on what is best for the patient. And typically, what's best for the patient in the medical conversation isn't necessarily preventative. And I was at my fellowship at Wash U in St. Louis and I did a combined fellowship in Nutritional Sciences, Obesity Medicine, and Geriatrics. And there was a very clear moment that I felt as if we and I had failed this one particular participant of this study. She was an older woman when I say older okay, late 40s, early 50s, has three children and she had always struggled with weight. And it wasn't a tremendous amount of weight, maybe it was 10 pounds, maybe 20 pounds, but she had always really struggled with her weight. And part of this was an intervention study looking at diet, nutrition, brain function, and I imaged her brain. So, my job as an investigator on this paper, the study that we were doing, which was a really large study was doing the medical base stuff. So doing the cardiovascular testing, doing the muscle biopsies, and also doing the brain imaging.

And I image this woman's brain and her brain looked like Swiss cheese. And at that moment, it was just so devastating to see what was to come for her because, at the time I was also working in nursing homes as part of my clinical fellowship. And I felt like we've really failed that here this woman was doing her very best to continuously be on the weight loss train. And what ultimately happened was she had destroyed her muscle and was going to be on a downhill spiral with some serious cognitive issues. There was a chance she wasn't going to be able to remember her kid's names in a decade. And it was at that moment that I realized we had been focusing on the wrong tissue. That we didn't have a fat problem, what we really had was a muscle problem. And if we had been focusing on our skeletal muscle what would have happened would have been a lot different. And that was kind of my epiphany.

Melanie Avalon: So, a question about that epiphany. So, the brain, is it skeletal muscle?

Gabrielle Lyon: No, so the brain is affected by body composition. We know that the wider the waistline, the greater the chances of low brain volume, and Alzheimer's, which is really what I studied what is, type 3 diabetes of the brain. And there are multiple reasons why an individual would get Alzheimer's. But above far and away the most preventable and common way in which an individual gets cognitive impairment or dementia, I shouldn't even say Alzheimer's, I should say dementia is being overweight.

Body Composition plays a huge role in dementia. And this starts in your 30s. Dementia starts in your 30s. So, the wider the waistline, the more glucose dysregulation you have the more elevated inflammatory markers, there are all kinds of issues that happen. And this really ultimately affects brain volume.

Melanie Avalon: So, is it the actual obesity causing that issue? Or is it the environment and diet that causes the obesity causes the brain issues.

Gabrielle Lyon: I think that it's really the obesity issue, because an individual, you know, and again, all these things are multifactorial, but we cannot discount that the more obese an individual, the more affected their brain is. Some people of course, can skate away from it. But the reality is, if you are overweight in your 30s, and you continue on that trajectory, you are putting yourself at a very unnecessary risk for dementia.

Melanie Avalon: I was going to talk about this later. But since we're talking about this now, I was pouring over studies about methionine restriction actually and how those seem to lead to weight loss. I'm overwhelmed and confused about the role of protein substrates.

Gabrielle Lyon: I'm so glad you asked this question. Let's take a step back and for the listener, there are 20 amino acids. In the natural environment, in the human body there are 20 amino acids. Everything is made up of these 20 amino acids in various degrees.

Of those 20 amino acids, there are nine essential amino acids. This means that the body cannot make it and you know we have to ingest it. Of those nine, methionine is what we call a sulfur amino acid and it is an essential amino acid, meaning we cannot produce it from the diet. And what's so interesting about methionine is exactly as you had mentioned, there's this concept of methionine restriction, which we're going to actually talk about, technicality is that it's a nutritionally indispensable amino acid. And really methionine where its function comes really in a multitude of ways. But ultimately, it donates a sulfur atom to cysteine.

And both methionine and cysteine play very unique roles in the body. One of which methionine is important and growth, it's also very important for glutathione production. When you hear methionine restriction, it's actually now called sulfur amino acid restriction. And where this actually comes from is rodent or mice models. And it's this idea that when you restrict the amino acid methionine, which is largely found in dairy and animal products, it's very low in plants, that your body generates what's called a integrated stress response. And this integrated stress response really plays a role in almost, I hate to say, cleaning the cells, I don't want to say autophagy, but it definitely plays a role in autophagy, now, this is in rodents. This is not actually in humans, this is rodents. And so, this is the concept of methionine restriction. And to date, all the studies are rodent or mice models. They're not human studies. And actually, I had one of the world's leading experts in actually methionine restriction, which is now called sulfur amino acid restriction. On my podcast that has not yet been released. She also came out of her name is Dr. Tracy Anthony, she also came out of Dr. Don Layman's lab. And that's just incredibly fascinating.

And what was so interesting is in my conversation with her, I asked her actually the very same question, and methionine restriction has really been popularized by a vegan diet is, in essence, a methionine-restricted diet. And I asked her, I said, where do you feel that this really plays a role? And she said we don't know where it actually plays a role yet in humans. But where it can be beneficial is because it up-regulates the stress responses, because of the unbalanced amino acids, there can be a place for it in the human diet. But we don't actually know any clear endpoints. For example, should a sulfur amino acid restriction be for one meal? Should it be for a day? Should it be for four days? What does it actually look at to measure health outcomes? We don't know the answer. But what we do know is when I was looking at this, there was one randomized control trial. So, this was interesting. This was a randomized controlled trial; it was a Mediterranean diet. And it was a low-fat vegan diet to improve body weight and cardiovascular, cardiometabolic risk factors. And this was Barnard.

Melanie Avalon: Dr. Neal Barnard?

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah. That's who the first author is.

Melanie Avalon: I've had him on the show. So, I'll put a link to him in the show notes.

Gabrielle Lyon: Well, I can't say I totally agree with what he has to say. And he is obviously a vegan advocate. So, we have to take that into account. But I was looking at this study that he was a part of, and when you look at the diet, the body compositions of the diet, they essentially put someone-- it doesn't talk about methionine restriction, but it was a vegan diet, and half the weight that they lost was lean mass. And to me, that's really extreme. So, half in a 16-week period, half the weight that they lost was lean mass and lean mass for people who are listening is obviously skeletal muscle and the organs. Organ, bone or not bone, but everything else, actually, do you think that bone is? I have to look.

But the point is, half of the weight that they lost was lean body mass, and that's a problem. So, your original question, is there a place for methionine restriction? I think it really depends, and I don't think those studies have been done in humans yet. And we have to really measure endpoints that are meaningful because there's a risk to doing this long term.

Melanie Avalon: I'm super curious, what did they title the study? Like how did they spin it?

Gabrielle Lyon: So, it's a Mediterranean diet, low-fat vegan diet to improve body weight and cardiometabolic risk factors?

Melanie Avalon: Okay, when they concluded did they even mention that lean mass part?

Gabrielle Lyon: No.

Melanie Avalon: Oh, okay.

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah. Also, I thought is dangerous. I think it's very much misrepresenting what can happen. But if you do look at the numbers they did regain once they went back to eating more high-quality protein. But there's a risk, and we have to understand. So, is methionine restriction I think that probably it's a tool, and definitely there's benefit. The belief of the benefit is really with certain types of cancers. But it doesn't mean that still, this is very proof of concept. And I don't know if it can be translated yet, in a safe way to humans. And I personally believe there's some benefit. I just don't know if we know how to do it effectively, yet.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, the reason I was thinking about it a lot recently was-- do you know, James Clement by chance? He wrote a book called The Switch. We were discussing the benefits of calorie restriction versus fasting. And were they dependent on each other? Were they independent? What was going on there? And he was just postulating that it was methionine restriction. So, then I was like, going down that rabbit hole.

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah, I'm super curious. Oh, and by the way, lean body mass would include bone. So just wanted to clarify for that.

Melanie Avalon: Another question about that, because you were saying how, if it is a benefit, we don't know the timeline on it. And actually, the study I was reading last night was looking at methionine restriction versus intermittent methionine restriction in mice,

Gabrielle Lyon: This is really important. So, the methionine needs in mice are different. The amino acids, rodents are fed a different kind of diet, it's challenging, but it is different. So, the mice models don't necessarily have a-- Again, it's a proof of concept, for example, there's percentage of body weight, their skeletal muscle mass is much higher. And the other thing with methionine restriction, it's in an immune-controlled environment. So, the rats were living in a sterile environment. Let's say you put people under stress, and you put them in a methionine-restricted state, which up-regulates this integrated stress response.

One of the things that when I was talking to Tracy Anthony, one of the world-leading experts in this area, she's saying, We have no idea what the other impacts would be because the rodents and the mice are in a very sterile environment.

Melanie Avalon: It's so important to consider what we can actually translate over. I haven't read the whole study, but I was just looking at the abstract. I have one that came out really recently. And it was actually saying that vegetarian or vegan diets are lower total protein, but not different in their ratios, I need to read the whole thing.

Gabrielle Lyon: Well, that of course wouldn't be true because we know that. Rule number one, we'd have to account for calories but vegan, vegetarian diets are certainly lower, typically, I guess it totally depends. But they are typically much lower in leucine and some of the essential amino acids and of course, there's lysine, the limiting amino acids in plants, we're looking at lysine and methionine are typically limiting.

Melanie Avalon: For listeners, can you explain what you mean by limiting?

Gabrielle Lyon: Yes, so when we talk about protein quality, protein is very complex. Again, protein is 20 amino acids, nine of which are essential. But when you look at the back of a food label, all you see is protein. But each protein, for example, the protein composition of a leaf is different than the protein composition of a bean, which is different than a protein composition of a piece of steak or a fish.

The amino acids that make up these foods, and these things are vastly different. And a very big shortcoming of what we're looking at, in which I think accounts for part of the confusion is we think about protein as a whole macronutrient, which it is. But it's a really complex one. Each of these amino acids do various different things in the body. And the initial amino acid recommendations came from-- its relatively new, we're talking about the 1940s, maybe a little bit before then, but really, the current protein recommendations came from trying to figure out a way to feed soldiers that were in World War II and figuring out a way to be able to meet the protein needs for individuals that were 1000s of miles away, and a large majority of them.

So how they determine this number because again, protein and nutrition science is relatively new. And one of the ways in which they determine this was through nitrogen balance studies and nitrogen is an essential component to protein and we need nitrogen for growth. We need nitrogen for multiple processes in the body, and the way in which protein needs were determined really translated from animal husbandry. So, this idea of how much carbohydrates and proteins could be fed to animals to allow them to grow, while keeping it as cheap as possible. And that's how they determine protein needs, They would measure-- so what is the maximum amount of carbohydrates and the minimum amount of protein to allow for protein turnover and ultimately nitrogen balance.

And what happened was, they estimated that the minimum amount of protein to prevent deficiency is 0.8 grams per kilogram, which is still now used today. Even though we recognize that nitrogen balance studies are really flawed, because again it doesn't take into account these individual amino acids, which we will eventually move to an indicator amino acid score, not yet there, but it's a different way of determining total protein needs. And I will tell you that the indicator amino acid-- is an indicator amino acid oxidation method.

And that the minimum amount of protein according to that is at least 1.2 grams per kilogram, as you know, where the RDA perhaps should be set at. So again, the initial recommendations, which are still to this day, 0.8 grams per kilogram was really based on these nitrogen balance studies of really younger men, you know, 19 years old, that were going to war and the average size of a male back then was 143 pounds, and the average female was 120 pounds, 121 pounds.

Yeah, this is really where we based these recommendations from. So, as you can see, there's somewhat of a disservice to that, because if you fast forward, people view the RDA, unknowingly as a maximum. But for example, Melanie, if you got sick, would you hesitate to take more than the RDA of vitamin C? You wouldn’t right? Even though the RDA for vitamin C is 60 milligrams, nobody goes. Oh, yeah, well, that's the maximum. Nobody does that. But for protein, people will say the RDA is based on, which is based on nitrogen balance studies, well, this must be the maximum.

When in fact, it's likely not. And we do have the indicator amino acid oxidation method that we know is likely much higher, at least 1.2 grams per kilogram per day. So, I hate to get lost in a rabbit hole because we're going to come back to this methionine restriction and some of the other protein kind of intake issues. But at a very fundamental level, you can see these flaws. The RDA is 0.8 grams per kilogram, it doesn't take into account the individual amino acids, which we know that individual amino acid needs are very specific for people. And we have to do a better job at making these more applicable to people if we're looking for optimization.

Melanie Avalon: It was my understanding that in general, the RDAs are erring on the side of not encouraging over supplementation like they're not going to put in numbers that they're worried would create toxicity from too much. So, they're going to be lower rather than higher, which would make sense with the protein situation. And I've so many questions from that.

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah. But I would say that the government doesn't necessarily all agree with themselves because the RDA is set at 0.8 grams per kilogram, but if you go and you look at the MyPlate. That set at I believe 1.5 grams per kilogram. So, the RDA is really the bare minimum and the goal is to prevent deficiencies and 97.5% of the population. So, they came up with point eight grams per kilogram, and you must understand that, you know, there's also the World Health Organization that protein is very abundant in the US, but that's not like that everywhere else. So, there is some sensitivity in terms of being and trying to make responsible recommendations.

On a fundamental level the RDA is the bare minimum, and they know that under no uncertain circumstances, someone who's ingesting 0.8 grams do better-- 0.8 grams/kilogram do better than someone who's ingesting one gram per kilogram per day. The individual with a higher protein diet will do better in metabolic outcomes when calories are controlled.

Melanie Avalon: So, here's a big foundational question that ties into all of that because you mentioned how that point A was determined based on, men at a certain time who were presumably a lower body weight and such but if it's a ratio, which again, I guess you were saying that you know that the ratio is too low, but if it's a ratio wouldn't it not matter what the body weight is that you're checking? Because it's more just about the ratio?

Gabrielle Lyon: No, I think what you're getting at? So basically, this is a really good question. So, I'm going to let you finish your question. This is a very good question that I think that your listener would really benefit from.

Melanie Avalon: Like clarification surrounding that. And then to add to that, what is determining the protein need? Like what factors?

Gabrielle Lyon: So basically, what I'm hearing you say, is that is protein dependent on-- Are you saying that? Is it dependent on body size or not?

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, like total muscle or--

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah, okay. So, let's break that down. The first thing that we have to think about is what is the total protein need of an individual. And protein is responsible for a multitude of factors from hair, from skin, nails, protein turnover, which is the body's continuously breaking down and building up, which is essentially 250 to 300 grams a day of turnover in the body, which is different than dietary protein. But turnover is about 250 to 300 grams of protein. As the body ages, the body becomes somewhat less efficient. Muscle becomes less efficient at sensing proteins, just the body isn't as robust, which isn't a great word, but isn't quite as capable as it once was when we are younger and in growth.

We have to understand that when we think about dietary protein needs, there's the difference between what is basic, and what is optimal. In my mind and the science would support that 0.8 grams per kilogram is enough to prevent deficiency. Okay, so basically, if you're getting enough calories, and you're getting 0.8 grams per kilogram, you're not going to be protein deficient. The average female, according to the [unintelligible [00:27:15] data gets about 75 grams of protein a day. The average male gets about 100 grams of protein a day.

Now, let's think about what a great recommendation would be. And I would argue that while the recommendation is incredibly variable. So, if you go and you look at the RDA, you could also then point out the AMDR, which is the average requirements, which are anywhere from 10% of the diet to 35% of the diet could be from protein. So that's not a great strategy because the percentage is so high. If you are eating 1,000-calorie diet, and the range of protein is between 10 and 35%, and 1,000 calories, 10% of that is what? Like 100 calories from protein. So again, there's a huge disparity in the recommendations and we have to account for that.

One thing to understand is that a great starting place is one gram per pound ideal body weight. And people can titrate up or titrate down based on that. And it doesn't matter if you are a male or female. If you are a 150-pound female or a 150-pound male and that is your ideal body weight, then I definitely recommend one gram per pound ideal body weight.

Now, let's talk about the next most important thing, So, a 24-hour protein intake is really important. The next thing to consider would be how are we going to distribute those calories. And how are we going to distribute those amino acids over the day? And there is one particular amino acid that one could make an argument for a meal distribution and that is leucine. And what's so fascinating is that if you are sub-threshold in leucine and I define that by the blood levels of leucine being low and not high enough to reach a threshold amount, a hyper amino acid level in the blood, which ultimately for people who are interested is two and a half grams of leucine will increase the leucine level in the blood enough to then trigger muscle-protein synthesis.

And this is really essential for helping with health and longevity. Okay, muscle is the organ of longevity. It's the most important factor in my personal opinion. So, after we determine the amount of protein an individual should eat, which I recommend is one gram per pound ideal body weight. And again, you can titrate up or titrate down, there isn't negative side effects with protein.

But we then have to consider that it's actually the amino acids that we're eating for. And these amino acids, in particular, leucine require a threshold amount. And that translates to 30 to 50 grams of dietary protein per meal feeding, and you could eat two meals a day, or you could eat three meals a day if you're fasting? However, you want to do it, but what becomes really important is you must reach that amino acid threshold because if you don't, you do not stimulate muscle-protein synthesis. And over a period of time, if you do not stimulate muscle, you will destroy it over a period of time.

Melanie Avalon: So, you're talking about the blood levels, like so leucine showing up in the blood? What is the timeline of that? So, is that immediately after a meal?

Gabrielle Lyon: Yes, so that's one reason why strategically, you would want to eat your meal at one time, you would want to spread out you're eating over an hour, or if you're drinking a protein shake depends on your absorption. But whether it takes 20 minutes to get all into your bloodstream. You want to consume it all at once.

Melanie Avalon: So, with blood glucose, how you can see a large spike and then return to baseline or you can see a lower spike, but a slow drip, basically of the glucose into the bloodstream. Does that happen with protein? Like if you have a ton of protein at once?

Gabrielle Lyon: I love this question because this highlights something that we spoke about. Are you ready?

Melanie Avalon: I'm so ready.

Gabrielle Lyon: This is exciting because carbohydrates, you said glucose? And you're absolutely right. The body has a very tight control of blood glucose. And it's one molecule? I mean it's one molecule of glucose whereas protein is 20 different amino acids at any given time. There are 20 different amino acids. So, can we measure it? Yes. Does it translate to much? Hmm, questionable? What's really important is that leucine level and that leucine level will get into the bloodstream, it will trigger muscle-protein synthesis, and that could last for five hours. And then, it's possible that it resets.

But typically, a lot of the research is done in that first meal. But could you measure it in the blood? You wouldn't necessarily need to because the studies have been done and we know that it's roughly about two and a half grams of leucine to stimulate muscle-protein synthesis. But it's a great question.

Melanie Avalon: Okay, so a hypothetical, like completely hypothetical, if there was a situation where you reach that threshold three separate times in a day, three separate times, and it's fast, like through a protein shake or something so you reach it, then you have your muscle-protein synthesis, then you're fasting and then you do it again like three times compared to one time, could you only in that massive bolus of protein, say it's the equivalent of 2.5 leucine but times three? So, it's like 7.5 leucine? I know it doesn't work that way. But is that the same benefits as three punctuated moments?

Gabrielle Lyon: What I'm hearing you ask is, is it good-- and totally correct me. Is it good to-- is there a benefit of stimulating it more than once? Is that what you're getting at?

Melanie Avalon: Like a practical example would be a person who has breakfast, lunch, dinner, reaches that threshold three times a day compared to a person eating a ton, but all at once. And like a one meal a day-type situation?

Gabrielle Lyon: Yes, great question. Well, first of all, the body will absorb all the protein that one ingests from a muscle-protein synthesis standpoint. Anything above around 55 grams of protein doesn't have muscle effects. And there's a lot of data in the literature, Don Layman, my longtime mentor looked at this, Doug Paddon-Jones, and the typical American feeding style is low-protein breakfast and lunch and then high protein at dinner. And what happens is, is you lose the ability to stimulate muscle, which is important for a multitude of reasons. Well, number one keeping healthy muscle there's also a thermic effect of food that happens with protein and it actually is really believed to be from turning on the mechanisms of the muscle.

I would say that number one, you have to think about what is your goal, if your goal is to optimize for body composition, then the first meal of the day whenever that is is going to be the most important. Because you are in a catabolic fasted state and optimizing for protein at that time is going to be the most important.

And let's say that's at 11. Your next meal, if your next meal is a couple hours later, and it's a snack, and it's a lower amino acid threshold, it's okay. I would be okay with it. Let's say you got 20 grams and then your last meal of the day was closer to 50. So, you're really optimizing for muscle-protein synthesis. I think that that would be a fantastic strategy. This strategy of book ending each meal, so, if it's the first and the last meal with a more optimal protein intake, I think is going to be more beneficial than a single meal of higher protein.

And arguably, a lot of those studies have been done, but one thing to consider is that from a practicality standpoint, you have to set yourself up for success. And eating one meal a day, typically, people will overconsume or if they're not overconsuming, their metabolic rate can slow down. If you train your body to feed off of 800 calories, then you train your body to feed off of 800 calories and your energy expenditure decreases. And that would not be an optimal strategy. I hope that answered your question.

Melanie Avalon: A clarification question, because you were saying about earlier how if you did have a massive bolus that maybe that I don't think use the word slow drip, but we don't know, but maybe, it could be five hours of things being stimulated?

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah. It's just how long mTOR stays stimulated. Yep.

Melanie Avalon: Basically, because what I do. [giggles] What I do is I do a “one meal a day,” but I eat for about four or five hours and it's at night. I probably eat around between 200, 250 grams of protein. So, I'm just wondering practically like, “What that's doing?” Am I only reaching muscle-protein stimulus once because it's all at once?

Gabrielle Lyon: Through dietary mechanisms? Yes. The other way to stimulate muscle would be through exercise. But I would consider-- Again, it depends on what your goal is. But I would consider breaking it up. Two meals a day would be better than one from a muscle benefit standpoint.

Melanie Avalon: And that's a good thing to clarify for muscle maintenance and preservation or if I was looking for muscle growth and then, I guess, we'd have to clarify.

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah. Well, for muscle maintenance, again, the 24-hour protein intake is most important. I'm assuming you're young. And so, one meal a day for you could be adequate. It doesn't necessarily mean that it's optimal. Because again, muscle utilization is only going to utilize 50 to 55 grams of that. It doesn't mean that you won't utilize protein for other things. But when it comes from really maxing out muscle protein synthesis which over a period of time, the goal is to continue to stimulate healthy muscle and really, I hate to say hypertrophy, because it's not certainly everyone's goal, but having the capacity to maintain healthy body composition. And I really say this with some hesitancy because there are multiple ways to do things. When you're young, you have ton of flexibility.

Melanie Avalon: You're speaking about that cap of 50 grams being used for actual muscle. So, beyond that, the rest of the protein that is catabolized, does it--? Because people will say, “Excess protein becomes glucose.”

Gabrielle Lyon: No, protein becomes glucose. For every hundred grams of protein an individual ingests, you generate 60 grams of glucose and that's through the process of gluconeogenesis. You have to deal with the carbon skeleton.

Melanie Avalon: People on the internet like rabbit hole tangents will debate if gluconeogenesis is demand driven or substrate driven. So, it's substrate driven.

Gabrielle Lyon: Probably, a combination of both. It's probably a combination of both. The body doesn't exist in one way or another. If an individual is in a fed state, then obviously, they're having to dispose protein. But whether it's demand or substrate driven, it's probably a combination of both. It is probably a combination of both. It depends on the way in which you feed in general. So, for example, if you eat a higher protein diet, the body becomes better at managing protein and more efficient at gluconeogenesis versus if you are a high carbohydrate eater, then your body becomes dependent and you'll have greater swings in blood glucose because you're required at that time-- Not required, but you're more efficient at utilizing the glucose. You know, the body's expecting that from the diet.

Melanie Avalon: I'm so glad he said that. That was one of my questions was, because I've been following such a high protein diet for such a long time, does your body preferentially adapt certain enzymatic processes to--

Gabrielle Lyon: Yes.

Melanie Avalon: How fast has that happened? Do you know?

Gabrielle Lyon: It typically for an enzymatic adaptation is a week to two weeks. For example, when we transition people off of—when we begin to add in more higher quality proteins, we typically give them-- You don't start someone from zero protein to 100 grams. You give them two weeks to adjust. A week to two weeks to begin to adjust slowly.

Melanie Avalon: You mentioned the exercise piece being another way to stimulate muscle-protein synthesis. So, I have a huge question about this. I've started doing EMSculpt. Have you ever done that? Other forms of it might be like e-stim?

Gabrielle Lyon: Yes, yes. Amazing.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. For listeners, these devices that stimulate muscle contractions while you're just laying there, it makes it contract deeper than you ever could consciously and really intensely. And they say, it's the equivalent of like 20,000 crunches, or 20,000 bicep curls, or 20,000 triceps curls all in 30 minutes. What I'm fascinated by is, A, I have seen really profound body composition changes from doing it. But B, so, you do one session and then they sit while you do multiple sessions. But they say from your first few sessions that you will continue to see benefits and growth for how many days? 30 to 60 days? I'm super curious about this genetic, I guess or epigenetic. Whatever's happening in an exercise and the potential for growth, the timeline of that, how far out does that extend?

Gabrielle Lyon: I think that's a really great question. I don't know what the e-stim and I can tell you that putting on muscle, it's totally variable depending on your level of training. A very well-trained individual will struggle to get every one of those pounds on versus an untrained individual could put on 20 pounds of muscle in a year. I think there's also a lot of variability in terms of how much an individual can put on. What we do know is for muscle hypertrophy it does require mechanical tension, which you provided. It does require metabolic stress, which you provided. It does require ribosomal biogenesis, which is the generation of protein, and then it does require calories. Calories can come from protein and combination of carbohydrates. And ultimately, that is what is also required in terms of muscle growth and hypertrophy.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, because it was a paradigm shift for me going into it, because I was always thinking on a 24-hour timeline. You work out, and then you eat that day in, and that's where the growth is happening. But the concept of creating the stimulus and then the body continuing to remodulate and grow that muscle for a month was really interesting to me.

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah, it's really interesting. And then we also have to think, does the exercise--? We know that the exercise stimulates mTOR. But in order to get that protein synthesis, we need all these other things. So, again, these are really good questions and really good considerations.

Melanie Avalon: So, excess protein, going back to that question about reaching the 50 cap and then what's happening to the rest of it. You mentioned earlier, I think you said there is not negative side effects to excess protein?

Gabrielle Lyon: No, we actually haven't seen them. There's a recent meta-analysis from Stuart Phillips that talked about kidney function and protein, as well as there's information out there on bone and protein. Protein is required for bone protection, formation. This is what protein is made from. Bone is made from protein. In addition, in terms of kidney function, it can improve glomerular filtration rate. That was in the Institute—Institute of Medicine talks about this. Again, this is not talking about someone with active kidney disease. I even think that they have begun to change those recommendations. Well, we haven't seen any level that protein has become toxic. The body can really handle the urea and ammonia very well. We just haven't seen it yet.

Melanie Avalon: Does that relate to the BUN?

Gabrielle Lyon: No. So, blood urea nitrogen, typically, depending on what's happening. It's not necessarily a direct measure. One of the reasons an individual or physician will look at BUN would be more for hydration status. The BUN-creatinine ratio is not amazing for identifying filtration rate as a physician. I typically add in a cystatin C which is an additional marker because the creatinine can change based on muscle mass.

Melanie Avalon: When you see a high ratio what normally causes that?

Gabrielle Lyon: Well, usually, if an individual has a high BUN, they likely just need fluids or hydration. Yeah, that's probably more than number one.

Melanie Avalon: I know you're not a doctor giving me medical advice. Mine’s always high and I've always wondered if it's from my high protein diet. The doctors tell me it's probably from the protein intake.

Gabrielle Lyon: Maybe.

Melanie Avalon: I eat so much protein. [laughs]

Gabrielle Lyon: I think a better indication would be, the goal of looking at BUN is really in combination with creatinine, but really looking at hydration status as well as filtration rate and that is better indicated when you get a cystatin C.

Melanie Avalon: Is that the panel where they categorize, if it's African-American or not, the filtration rate?

Gabrielle Lyon: Yep.

Melanie Avalon: Why is that?

Gabrielle Lyon: Difference in kidney functions just reads that whatever the lab values have determined,

Melanie Avalon: Okay, gotcha. Another question for you. So, especially in the keto world, and the fasting world, and the paleo world, it is said that the body preferentially burns fat rather than muscle. Is that actually the case or people who are insulin resistant? Do some people, their body actually burns muscle before fat, especially have stubborn fat stores?

Gabrielle Lyon: I think this is a very complicated question. The preferential fuel source for muscle is fatty acids, in general. The body, again, this is not intended to be a black and white answer, but the body-- Protein is incredibly valuable. One reason why the body would begin to utilize muscle is, if those amino acids are needed, you can spare protein. Meaning, you can spare muscle if your calories are high enough and if your protein is high enough. Let's say, you had a higher calorie diet. Your body would likely be able to spare muscle. It's not going to utilize muscle. But again, if you're eating a high-carbohydrate diet with no protein, then the body will depending on what's happening quite possibly tap into those amino acid reservoirs. It depends on what's happening.

Now, the other aspect of this is, if you were to go on a low-calorie crash diet, you better believe that you will be losing lean tissue. Again, we talked about lean tissue, being organ, skin, bone, water, whatever. But if you correct for a higher protein diet during that time with some kind of physical activity, you will spare muscle and then you will utilize fat for storage or you will use fat for energy.

Melanie Avalon: So, what are your thoughts on protein-sparing modified fasts?

Gabrielle Lyon: Fantastic. I think it's fabulous.

Melanie Avalon: For losing-- weight loss?

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah. And I'm not giving anyone medical advice here. I'm not telling you to do it. But I think, Melanie that that's really a fantastic thing if individuals wanted to get with their provider. But a protein-modified sparing fast is phenomenal.

Melanie Avalon: I'm glad to hear you say that. That's what I think so. [laughs] Okay. And then something that I've heard you talk about is myokines?

Gabrielle Lyon: Yes.

Melanie Avalon: I was wondering if you could tell us a little bit about those or what that is?

Gabrielle Lyon: I would love to. We must understand that we often think about skeletal muscle as fitness. We think about it in terms of how our body looks, our strength, our power. But muscle is so much more than that. It is an incredibly dynamic tissue that we can voluntarily command. 40% of total body weight, it is a regulator of many things above and beyond strength. Contracting skeletal muscle releases something called myokines. These are cytokines or peptides that are synthesized and released from muscle tissue in response to muscular contraction.

A woman named Pedersen, I believe she's in Copenhagen, who has really paved the way. She's an exercise immunologist. I believe she's an MD, PhD. She has really paved the way in following up on this research. What's so fascinating is myokines act locally within the skeletal muscle. They also regulate other tissues, and they travel throughout the body, and they interface with liver, and brain, and adipose tissue through receptors. And not only that, it plays a role in nutrient partitioning. For example, the way in which we use carbohydrates and the way in which we metabolize fat. There are about, I don't know, there hundreds of different myokines.

The most well-studied myokine is interleukin 6. This was found in the early 2000s. And again, the most well-studied myokine-- What's so fascinating about interleukin 6 is that when an individual is training, whether it's resistance exercise or cardiovascular exercise, the skeletal muscle releases interleukin 6. And interleukin 6 increases glucose disposal, increases the uptake of glucose and fatty acid oxidation, and it does a whole host of things as it relates to nutrients.

One other really interesting thing is, it seems as if interleukin 6 is secreted more when someone is in a low glycogen state. That is right. Glycogen is the storage form of carbohydrates, typically a muscle. When an individual is in a low glycogen state, typically, more interleukin 6 is released. Interleukin 6 oftentimes people think of it as a negative aspect released from cells of the immune system. But again, it is actually released from the muscle as a myokine. Incredibly interesting.

Another myokine that is pretty popular, people might not even realize that myokine is BDNF, brain derived neurotrophic factor. This is important in the regulation of neuronal survival, plasticity growth in the brain. Perhaps, even having a really important impact above and beyond mood. Yeah, and there's a whole host. There's interleukin 15 and a whole bunch. But again, in these myokines interface with the immune system and really play a role in regulating other aspects of the immune system.

Melanie Avalon: Fasting has been shown to raise growth hormone when we're fasted. Even though, that's not exercise and it's not protein, is that a way to ultimately stimulate muscle-protein synthesis when you eat again?

Gabrielle Lyon: No, fasting would be a catabolic state. Fasting would not stimulate muscle-protein synthesis. But I like where you're going with it. You're thinking, “How could we stimulate it in alternative route” is what I'm hearing you say?

Melanie Avalon: So, what's happening when we're fasting and our growth hormone is up?

Gabrielle Lyon: In my mind, it's really just a way to counter regulate nutrients to protect against low blood sugar. It just seems to be a protective mechanism.

Melanie Avalon: Okay, interesting. You don't think there's, I'm just super curious, a beneficial effect with fasting and muscle growth, because of the race growth hormone and then when you eat again.

Gabrielle Lyon: I feel it would be very transitory. I do think that fasting in and of itself is counter-- is in opposition to muscle-protein synthesis.

Melanie Avalon: Okay. So, those signals are likely just protective. That's why they're--

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah. I don't know the answers to why mechanistically-- The only thing that I can think of and the only thing that I've read is just as a counter regulatory mechanism to protect against low blood sugar. But again, I don't totally know that answer. In terms of, is the growth hormone stimulus enough to generate muscle-protein synthesis? I would say no.

Melanie Avalon: Okay. That's really interesting. Actually, and related to that and related to things earlier talking about a genetic stimulus, and then a long-term effect from that. This was in rats. So, again, hard to know how it translates exactly. But I was reading that mice, were they actually limited their food intake during the first 20 days of their life, created a long-term genetic profile? Were they had greater longevity? Do you have any thoughts? I guess, that'd be a larger question about humans and babies. So, when we're, yeah, infants.

Gabrielle Lyon: It sounds like they restricted them. It sounds like they almost essentially malnourished them.

Melanie Avalon: Mm-hmm. And then they ultimately had longer lifespans and then they had mice also in that same early phase. They were actually given growth hormone and they had shortened lifespans in the end.

Gabrielle Lyon: That was Tracy Anthony's study. That was some of her work.

Melanie Avalon: That's who you just had on your show?

Gabrielle Lyon: That’s right, just, yeah, we haven't released it. She basically said that what it did is and maybe this wasn't her work we have to look, but she replicated these studies-- I believe she replicated these studies. What she said was that it was essentially created mice that were half the size of a regular individual. And that when you added growth hormone, it did what you would expect it to do. But at some point, the body builds antibodies to the growth hormone.

Melanie Avalon: That was the issue? Was the body creating the antibodies?

Gabrielle Lyon: There were likely multiple issues. But you can't have that would translate to a human, if you-- Calorie restriction can potentially improve longevity. But these questions are very nebulous in the sense of, “Well, what is longevity? Is it six hours? How are we determining these endpoints?” I think that that has to be determined before we can really understand what that translates in humans. Because we're not looking at any endpoints. What are the endpoints? In terms of protein restriction that's essentially malnourishment. If you then renourish the animal, the animal will probably grow but in terms of calorie restriction, not sure early on in life that would be a good strategy.

Melanie Avalon: That's something big probably, it couldn't even ethically tested humans. What was really interesting about all of that is to what you just said about, what we actually see long term in real life. When I had Valter Longo on the show because he's a big advocate of low-protein diets. He says the exact same thing that we're saying right now, but he draws the opposite conclusion, which is that he thinks if we look at the data, it's low protein for longevity.

Gabrielle Lyon: But that's never been shown in humans. So, my question would be, “Why isn't that shown in humans?” So, if that's the case, why is there not one randomized controlled trial that shows that in humans?

Melanie Avalon: So, like Loma Linda, for example. Are they low protein?

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah.

Melanie Avalon: And they're living long?

Gabrielle Lyon: I believe they are. But that's not a randomized controlled trial. That's epidemiology. Maybe they're meditating, maybe they're outside in nature. You can't say that just because I would disagree with Longo and say well, we know that throughout aging, muscle mass improves survivability in all-cause mortality. If you put an individual in all-cause mortality, right? We know there are multiple randomized control trials looking from Stuart Phillips lab, to Doug Paddon-Jones, to Don Layman to say, those with a higher protein diet improve lean muscle mass, improve endpoints of triglycerides, and blood pressure and fasting insulin and blood glucose.

My question would be, “Well, if we know that skeletal muscle is so pivotal in survivability when you put people on a low-protein diet, we know that they have lower skeletal muscle and lower bone density.” Could they live five hours longer or a week longer or a year longer? I don't know. It's never been done in humans. But I guess, the question is where does someone place importance? I would argue and say, “You have to protect skeletal muscle at all costs.” I'm a trained geriatrician and I took care of those people at the end of their life. It's pretty ugly. The idea that one would say, go low protein, when we know that the RDA is the minimum protein amount to prevent deficiencies. And now, to make a recommendation to go beyond to go lower than that, when actually it's likely for more optimization would be higher, I think it's a bad strategy.

Melanie Avalon: I asked him, because he was talking about the role of IGF-1 being overstimulated and things like that. I asked him about what I do, which is basically, a large amount of protein, but then I'm fasting every day. So, maybe that's mitigating the chronic IGF-1 stimulation.

Gabrielle Lyon: Is it chronic? But then I would argue and say, “Well, but IGF-1 is stimulated through exercise.” There's a role in overconsumption of carbohydrates, and obesity, and elevated levels of IGF-1. Why would someone point to protein and make that correlation? I think that's unusual. There was also a letter to the editor in response to, he was part of a paper that was pretty controversial in cell metabolism. He published a paper that he linked cancer and protein or something like that was IGF-1 and there was a huge backlash and a letter to the editor written about the flaw data and the exaggeration of the conclusions to the public. And no serious, negative health consequences for adults seeking to maintain muscle and protect against sarcopenia. This can be found online. But I think that that's really important to note that it's very, very risky when things are taken out of context.

For example, I'll read to you a response from these world class scientists, okay? This is based on what Longo is talking about and it says, “This study shows a relationship with growth factor, IGF-1 in cancer risk,” which is already known. This is what this Professor Sanders says. However, the relationship between IGF-1 levels and protein intake is far more tenuous in humans. It says that the cross-sectional data suggests animal proteins to be associated with increase in IGF-1 levels, but there is lack of evidence from any controlled feeding studies that IGF-1 levels fall when animal protein is restricted. There's just a huge letter to the editor. There're all kinds of stuff. So, I think it's misrepresenting rodent and mice data to push something that people believe which may not be accurate.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, I open this conversation by saying, I'm haunted, it's just because all of these debates. You were talking about being with people at the end of life and problems with sarcopenia and such. Because one thing that Longo will say and I think a lot of the figures in that movement will say is, they do admit that when you're older, there's an increased need for protein. I think you said this at the beginning, but is that just due to a reduction in the ability to use protein or is there actually a need for more protein, if they could in theory use protein the same as they could when they were young? Is it digestive enzymes down and enzymatic processes down? Why does it--?

Gabrielle Lyon: I think that that's a mistake. I think that you always need optimal protein, because when you are young and healthy that is the time to build your body armor. You have to build your body armor and you have to build your reserve. You don't want to wait until you're 70 to start weight training. The idea that one would restrict protein throughout the most formative years and throughout the time in which they have the greatest anabolic potential is a huge mistake in my mind. I've seen it. Then, all of a sudden, what? You hit the magic number of 60 and then you increase your protein intake, but what about all the damage and what about all the missed opportunities of optimizing for skeletal muscle all those decades? I would argue and say that it's just incorrect. And yes, the body needs more protein as it ages. There’re two ways to really stimulate muscle and that is through resistance exercise, which most people aren't training harder as they get older. Their training, a little less effectively.

The other aspect is the efficiency of protein utilization goes down, which is another reason why you need more. However, I would argue that if you optimize for protein throughout life, you have a much better chance of meeting important health markers throughout your life, like, better body composition, lower triglycerides, better blood pressure, better glucose regulation, lower insulin levels. There's a whole host of other reasons why you would want to optimize for protein rather than restrict protein, which we know. I'm sure people who've done it.

Protein is important for neurotransmitter production. It's important for injury, it's important for so many things that it's the most important macronutrient and it’s the most controversial because it is misunderstood. The idea that when someone hits some magical age that we would all of a sudden restricted or all of a sudden start eating it, again, it's a complete missed opportunity.

Melanie Avalon: Do you know what would be the longest live population with a high protein intake?

Gabrielle Lyon: I have no idea.

Melanie Avalon: I need to look that up.

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah, I have no idea. I'm sure they're out there.

Melanie Avalon: And then, did you say that they are potentially changing the system to show ratios of amino acids rather than total protein?

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah. I don't with not anytime soon, but maybe within the next year, they'll add in a protein score. I'm not entirely sure. I'm not privy to all that information. [chuckles] But I do believe that at some point-- Let me rephrase that. I know at this point in time that that is something that is going to be individuals are working on.

Melanie Avalon: Oh, wow. That would be an overhaul. [laughs]

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah, but it's an insanity. Isn't that crazy to think about it that we just are slow to catch up? We're slow to catch up. At the end of the day, I think everybody who is in this space really wants the same thing. We all want people to live a better life. I believe that the only way that's going to happen is if we have more transparent conversations about where our biases are, what we've seen, what is actually true, and what does the data support? What is the high-quality data support combine that with practical experience, you know?

Melanie Avalon: No, thank you for saying that, because that is literally, exactly the way I feel. Even when we're talking about the Longo stuff, because my question is just like, “If this is the case, why is it pushing an agenda or why are certain things thought the way they're thought?” Talking to you, it sounds it's a lot of misconceptions.

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah. I think scientists are humans too, and they all come into it with their own biases. Yeah, I was working out this morning and I was thinking, “How do we merge the two?” I am definitely pro-animal products, but me being pro-animal products doesn't mean me being against plant-based nutrition. It's not. It's how do we come to some understanding where anyone can choose what they want and know how to do it in a way that is meaningful and appropriate to them with important health endpoints. I think that that's where we're at right now. Unfortunately, if the information is so misconstrued then people are going to run around like a chicken with their head cut off and not know what to do.

Melanie Avalon: And it's so moralized.

Gabrielle Lyon: Yeah, and that's the problem. At the end of the day, no. A whole fresh red meat is not bad for you. How else will we get our creatine? Where are we going to get these bioavailable sources of these nutrients? It doesn't make any sense. But if someone doesn't want to eat animal products, I totally get it and I can respect that and appreciate it. It's just a matter of, is dietary protein bad, should we be restricting it in our youth? No. Why would you do that? Could you do intermittent times of restriction? Maybe. Can we say that we have confirmed reasons why we know this to be true in human studies? No, we can't.

Eventually, I believe we will be able to and I think it's important to say, well, but I think an honorable thing to do would be to say, “Hey, these are rodent models. These are mice models. We don't see that in human data right now. What we do see in human data is, when people go more plant based, we see that they lose lean muscle mass or we see that they lose lean body mass.” But does that mean that they have to? No. I think that if there are strategies to increase overall dietary protein, even if it's plant based and really increase their training, is that doable? Yes. But again, I think these conversations need to be more inclusive, not so uninviting.

Melanie Avalon: I could not agree more. That's why with this show, I love bringing on people from all different perspectives, because I have no idea how we would come to a place of truth if we're not hearing everything. Yeah, well, thank you. This has been absolutely amazing. I could pick your brain for hours and I can't thank you enough for the work that you're doing. There needs to be more people talking about this. Just like talking to you now, hearing your perspective on it, it's just so invaluable. So, I cannot thank you enough for everything that you're doing.

Gabrielle Lyon: No, I'm so happy to be able to do it. I feel we'll have to do a part-2 on this.

Melanie Avalon: You're going to have to come on The Intermittent Fasting Podcast. That will be amazing. The last question that I ask every single guest on this show and it's just because I realize more and more each day how important mindset is. So, what is something that you're grateful for?

Gabrielle Lyon: I actually ask my daughter this. We ask as a family, we go through this every single night, and I will say, I was thinking about. I actually start the day with this question. As I was sitting here, I'm writing my book and I feel so grateful to be able to have the opportunity to take the knowledge from some of these really great scientists and be able to share it. It's very meaningful. I truly hope someone gains some insight, or wisdom, or feels heard during this podcast.

Melanie Avalon: Well, you definitely did that and thank you so much. It's a rare talent to take the science and make it so understandable and approachable. To do it like we just said, not to be repetitive, but to do it with a clear awareness of people's biases and the ideologies that they're coming from, and the actual science of what's happening. So, thank you. This is amazing. I will be eagerly following your work.

Gabrielle Lyon: Thanks so much for having me, Melanie.

Melanie Avalon: Thanks, Gabrielle. Have a good day.

[Transcript provided by SpeechDocs Podcast Transcription]