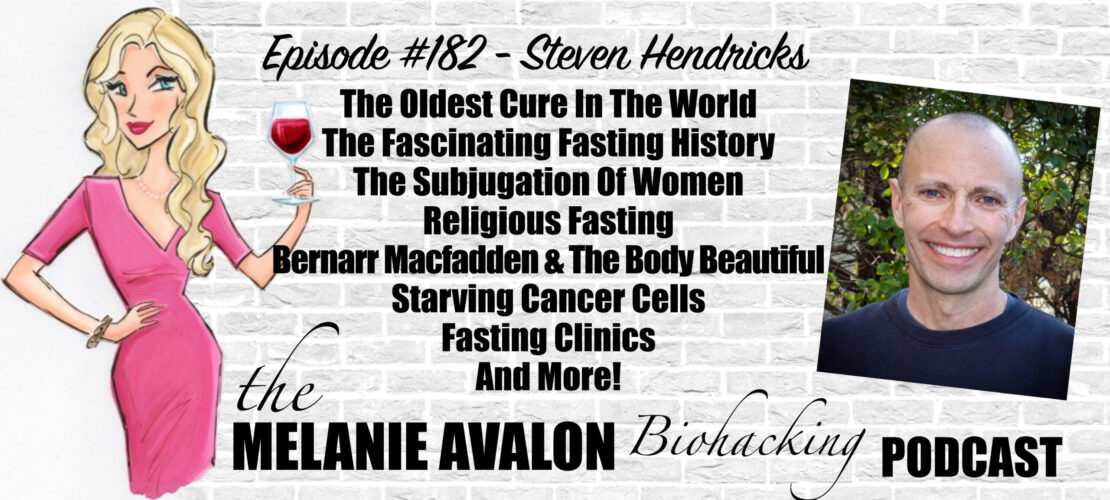

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #182 - Steve Hendricks

Steve Hendricks is a freelance reporter and the author of two previous books, one of which, The Unquiet Grave: The FBI and the Struggle for the Soul of Indian Country, made several best-of-the-year lists. He has written for Harper’s, Outside, Slate, and the Washington Post. Hendricks lives in Boulder, Colorado with his wife, a professor of family law, and his dog, a border collie cross.

LEARN MORE AT:

https://www.stevehendricks.org

SHOWNOTES

2:15 - IF Biohackers: Intermittent Fasting + Real Foods + Life: Join Melanie's Facebook Group For A Weekly Episode GIVEAWAY, And To Discuss And Learn About All Things Biohacking! All Conversations Welcome!

2:30 - Follow Melanie On Instagram To See The Latest Moments, Products, And #AllTheThings! @MelanieAvalon

3:00 - AVALONX SUPPLEMENTS: AvalonX Supplements Are Free Of Toxic Fillers And Common Allergens (Including Wheat, Rice, Gluten, Dairy, Shellfish, Nuts, Soy, Eggs, And Yeast), Tested To Be Free Of Heavy Metals And Mold, And Triple Tested For Purity And Potency. Get On The Email List To Stay Up To Date With All The Special Offers And News About Melanie's New Supplements At avalonx.us/emaillist! Get 10% Off Serrapeptase 125, Magnesium 8 AND Berberine 500 At avalonx.us And mdlogichealth.com With The Code MelanieAvalon!

Text AVALONX To 877-861-8318 For A One Time 20% Off Code for AvalonX.us!

5:35 - FOOD SENSE GUIDE: Get Melanie's App At Melanieavalon.com/foodsenseguide To Tackle Your Food Sensitivities! Food Sense Includes A Searchable Catalogue Of 300+ Foods, Revealing Their Gluten, FODMAP, Lectin, Histamine, Amine, Glutamate, Oxalate, Salicylate, Sulfite, And Thiol Status. Food Sense Also Includes Compound Overviews, Reactions To Look For, Lists Of Foods High And Low In Them, The Ability To Create Your Own Personal Lists, And More!

6:15 - BEAUTYCOUNTER: Non-Toxic Beauty Products Tested For Heavy Metals, Which Support Skin Health And Look Amazing! Shop At beautycounter.com/melanieavalon For Something Magical! For Exclusive Offers And Discounts, And More On The Science Of Skincare, Get On Melanie's Private Beautycounter Email List At melanieavalon.com/cleanbeauty Or Text BEAUTYCOUNTER To 877-861-8318! Find Your Perfect Beautycounter Products With Melanie's Quiz: melanieavalon.com/beautycounterquiz

Join Melanie's Facebook Group Clean Beauty And Safe Skincare With Melanie Avalon To Discuss And Learn About All The Things Clean Beauty, Beautycounter And Safe Skincare!

The Oldest Cure in the World: Adventures in the Art and Science of Fasting

10:35 - the research that went into the book

13:30 - steve's personal story

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #87 - Dr. Alan Goldhamer

18:30 - dr. Henry tanner, the father of fasting

26:25 - why don't doctors believe in the power of fasting?

28:45 - HOLDON BAGS: Reduce single-use plastic! HoldOn makes heavy duty, plant-based, nontoxic and 100% home compostable trash, bags, sandwich bags, and gallon bags to help combat our toxic plastic environment! Sustainability has never been more simple! Visit holdonbags.com/MELANIEAVALON and enter code MELANIEAVALON at checkout to save 20% off your order!

31:50 - heroic medicine

35:45 - historical theories about endogenous energy sources during fasting

38:00 - why didn't people notice it was fat that was being burnt for energy?

40:00 - fasting in greek history

46:35 - how do we know these famous quotes aren't real?

49:00 - fasting in religion

52:45 - women taking on the role of fasting

59:50 - the oppression of women through diet control

1:02:40 - LOMI: Turn Your Kitchen Scraps Into Dirt, To Reduce Waste, Add Carbon Back To The Soil, And Support Sustainability! Get $50 Off Lomi At lomi.com/melanieavalon With The Code MELANIEAVALON!

1:05:35 - Jainism

1:09:20 - dying of starvation

1:11:15 - the loss of fasting in christianity and the creation of lent

1:20:00 - Bernarr Macfadden

1:26:30 - upton Sinclair

1:33:40 - the dismissal of fasting in fasting in modern medicine

1:36:00 - LMNT: For Fasting Or Low-Carb Diets Electrolytes Are Key For Relieving Hunger, Cramps, Headaches, Tiredness, And Dizziness. With No Sugar, Artificial Ingredients, Coloring, And Only 2 Grams Of Carbs Per Packet, Try LMNT For Complete And Total Hydration. For A Limited Time Go To drinklmnt.com/melanieavalon To Get A Sample Pack With Any Purchase!

1:39:05 - "tricking" people into fasting

1:40:50 - valter longo and fasting mimicking diet

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #115 - Valter Longo, Ph.D.

1:47:30 - fasting clinics

1:50:30 - Alan Goldhamer's Data on blood pressure

1:54:30 - Steve's experience at the clinic

1:57:45 - the future of fasting

2:01:05 - steve's fasting practices

Early Vs Late-Night Eating: Contradictions, Confusions, And Clarity

TRANSCRIPT

Melanie Avalon: Hi, friends, welcome back to the show. I am so incredibly excited about the conversation that I am about to have. Oh, my goodness. So, the backstory on today's conversation, I get, I guess, hit with a lot of people with books that would love to come on the show. And sometimes, I get information from an agent or publicist about a book and it's just an immediate yes. I don't even need to have even started reading the book to know I want to interview this person. So that happened with Steve Hendricks, who has a new book out called The Oldest Cure in the World: Adventures in the Art and Science of Fasting. Obviously, I saw the title and I was like, "Yes, full speed ahead." And then, I got the book and, oh, my goodness, friends, I was blown away by this book. I spend so much time reading studies about fasting and just thinking about fasting, so much of my life is about fasting.

There is so much information in this book that I had never even remotely, possibly, even briefly heard of. It's honestly mind blowing, especially when I think about how I'll often read scientific studies about fasting. There'll be like a sentence where they'll be like, "Fasting has been used for so many years in history." This book covers all of that. How fasting has been used in history or not used, the forces that kept it going or were against it, all of the people involved. It's mind blowing. And then, not only is it the history of fasting, but Steve also provides his personal experience with fasting, which is super cool and dives into the science and lets us know where fasting is today. So, I have so many questions for this man. Steve, thank you so much for your time and thank you for being here.

Steve Hendricks: Oh, it's great to be with you, Melanie. I hope I can live up to that fantastic and very kind introduction. Thanks a million.

Melanie Avalon: I have so many questions for you. I want to hear your personal story, but just a question to start off because I'm so curious. This book is like a textbook and it's like all of this history. How do you find all of this information? Do you look at Wikipedia? [giggles] Where does one go to collect all of this information?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah, the difficulty is that it's not in any one place. But that's of course, what makes I think the book very valuable. What I wanted was to be both super comprehensive. It sounds like I checked that box for you, which is great. But I also wanted it to be lively. I wanted it to be a more vivid with characters, and stories, a very relatable chronicle that people could-- You wouldn't think of a fasting book as a page turner, but that was my aim. My aim was to have the pages just fly by, even though there was a lot of information. Now, where do you go to find it? The book is divided into three sections that are all intertwined and overlapping. But as you said, it's the history of fasting and the science of fasting, and my own experiences with fasting.

For the science of fasting, I go exactly where you go, which is reading those scientific studies and interviewing the most prominent researchers who have something interesting to say. The history was the trickier thing because there's so much written about the history of fasting and unfortunately a ton of it is wrong. So, you really have to dig pretty deep and quite often there was an academic at some point will have written a book about fasting for a certain 500-year period in the Middle Ages. Okay, awesome. Great. So, I've got that period covered. Now, what do I do about the other 2,000 years of history before that? It's a real mix. Sometimes I'm reading academic books, sometimes I'm reading their studies. In a few cases, I'm going to the actual Greek, or Latin, or whatever sources and I'm trying to find someone on social media who will be kind enough to translate sentences that I'm having trouble figuring out. I'm a reporter. So, I'm reporting on the work of academics. Unfortunately, while there's not as much out there about fasting as we'd like, there is a ton out there if you just uncover all the stones. That's what added up to the book.

Melanie Avalon: I'm just blown away. I can't even imagine how much you had to read to get to it. So, you check the box about the comprehensive history. You definitely check the box, the second one about being lively and creating characters and page turner. There were literally times my mouth dropped open when I read parts about some of these things happening, which we can get into in this show.

Steve Hendricks: If you could see me blushing now, don't stop, don't stop.

Melanie Avalon: No. Some of the stuff about the females fasting and the religious aspect of all of that, there're so many things. We can circle back to all that. But before that, your personal story. Obviously, this is in the book. I'll just say, friends, listeners, we're not even going to remotely touch on everything in this book. So, just get it now and you can hear everything. But you do share a lot about your personal fasting experience. So, could you tell listeners a little bit about that? You're a reporter. why did you become interested in fasting? Why are you writing about it now? I know you tried to write about it earlier and things happened with that. So, why are you where you are today?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah. So, I first started writing about fasting in an article that I published for Harper's Magazine about 10 years ago. That was back in a time where there weren't a lot of people fasting as there are today. It was viewed with a lot of skepticism. I wrote that article because I had come to become fascinated with fasting myself and I had practiced it myself. The center piece of the article was this 20-day fast that I had done. At that time, I was about 40 years old, maybe in my late 30s, when I did this. I fasted for two reasons, one of which was the one that so many people come to fasting for, "I just wanted to lose weight." Like a lot of people, I had put on a pound or two every year in my 20s and 30s. I'm 5'9" on a good day and I was weighing close to 170 pounds, whereas when I was at my lean in college, I'd weigh 140. Partly I just wanted to lose weight, but I'd gotten interested in fasting and learned about fasting in the first place, because I also was very interested in fasting for longevity.

I had originally started with caloric restriction, which, as most of your listeners probably know, just means sharply limiting how many calories you're getting every day while still getting all your necessary nutrients. The problem with CR, caloric restriction is it is just fiendishly hard to do. It is just impossible. You're walking around hungry all the time. And if you're a mere mortal like me, you're not some superhuman person, you just can't stick with caloric restriction. But the irony, of course, is that you can get many of the exact same benefits from a prolonged fast as you do in caloric restriction, yet you don't feel hunger. The irony is, by doing the most calorically restricting thing of all, just simply not eating, your hunger actually gets suppressed and so it becomes a much more doable thing.

So, this was very appealing to me. Someone who weighed too much and wanted to weigh less and was curious because I'd read these historic accounts of people who'd done long fasts. I wanted to see what it was like. Now. I'll caution and say, "Knowing what I know now, I would not undertake a 20-day fast on my own without some kind of medical supervision, because there are too many things that can go wrong." I'm not telling the audience what to do or what not to do, but I want to caution that fasting doctors have very good reason for saying, "You don't really want to be doing really long fasts on your own because some things could go wrong." But with that caveat, I did that 20-day fast. It went fantastic. I had a lot of ups and downs that a lot of other people have described when fasting, but ultimately, I found it to be a very satisfying experience. I lost all the weight that I wanted to lose. So, it was fantastic.

I wrote this article and I'd like to tell you that in the 10 years since I wrote that article, it's all been a carpet of rose petals in my path. But that has not been the case. We can talk about that. But my health actually deteriorated over the years throughout my 40s. I'm 52 now and it was eventually fasting and I believe dietary change that have rescued me.

Melanie Avalon: That was something that I loved was that you've had so many experiences with fasting. For me, I started doing intermittent fasting in college and I did the type I'm still doing today, which is one meal a day, eating at night. I haven't done a long, extended fast like you. I haven't done-- You've tried ADF, you've gone to fasting clinics. I was really thrilled, because in the opening of the book, you talk about, and throughout the book, Alan Goldhamer, who I've had on the show at TrueNorth and I was super excited to hear your experience there. It's super valuable I think that you have had experience with all of these different fasts.

There's something I wanted to comment on really quickly. I love the distinction that you have between fasting and calorie restriction. For example, you talk in the book about people looking at World War II and starvation and saying, "Well, if fasting has all these health benefits, why did people not get really healthy from starvation in World War II?" It's the subtle nuance of having just enough calories to not let you actually be fasting. And then, they're also malnourished not having enough food. There's so much complexity and I'm so happy that you tackle all of it. There're so many directions I want to go with this. You talked about the colorful characters in the history of fasting. I imagine because there were so many different people. Why did you settle on Dr. Henry Tanner as the father of modern fasting, and why did you choose to open the book with his story and everything that he did?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah, great question. So, Henry Tanner was this doctor who was born in the 1830s, I would say he was a doctor. He was indeed a doctor, but not a medical doctor. He was what was then called an eclectic doctor, which is something like a naturopath today. So, he was an alternative medicine practitioner and somewhere along the way, he had picked up fasting, short fasts, a couple of days here, three days there as a useful tool. Well, it turned out in 1877, he had fallen on hard times. He had just lost his wife. He was living in Twin Cities of Minnesota then and he had all kinds of ailments. He had a stomach condition that may have been a stomach flu, he had basically something that sounded like a nervous breakdown, he had heart problems and so on. He decides then that he's going to fast long enough to either cure himself or by one account kill himself and he didn't care what the difference was.

So, I started with him in part, because he's such a quirky character. I'm not very good at remembering my own quotations and so on, but some of the things that he said were just out of left field, but also because he was the first person who in a case study scientific kind of way sat down and said, "Well, I'm going to fast and then I'm going to see if fasting cures me and see what happens." And he did it. There had been previous doctors along the way who had been noticing these cures and trying to write about it, but he did it in a way that got the message out to the entire world. So, what happens is, he does this fast. It was expected, people thought at this time you could not go longer than eight to ten days without food or you would die.

What Tanner found is, when he reached eight to ten days, not only had all of his problems started falling away and all of them eventually got cured in accounts that we have of this fast, but he felt even better. He felt even stronger than he ever had before. He ended up finding out on day 20 something or whatever of his fast, because he just kept going and going, because he was curious to see how long this fast could go without his suffering. He would find himself walking 10, 15, 20 miles a day, which is vigorous exercise for 1877. That could be a lot of exercise today, right? So, he does this fast, he cures himself, he breaks his fast after 41 days. He had no intention of advertising it, but a friend of his, another doctor who had helped supervise him during his fast reported it in a medical journal in Chicago. It got out to the world and everyone just completely ridiculed him and said, "He must be lying. There's no way that you could fast this long."

Through a series of other events, he's wanting to prove himself to redeem his name. And an opportunity arises for him to go to New York City three years later in 1880, and there to repeat his fast of 40 days on a stage in front of people in New York. He was completely ridiculed at first, but there was this prurient interest in his fast, because "Oh, my gosh, he's going to fast beyond perhaps eight to ten days. What's going to happen? Is he's going to die on stage?" Interest grew and grew. This was a presidential election year. He was getting more coverage than the presidential contenders. His feat was being recorded all over the world. He went through the eight to ten days with no problem and kept fasting for 20 days, and then 30, and eventually broke his fast at 40 days.

What happened with this, unfortunately, when he was in New York, he didn't have anything wrong with him. He wanted to prove that fasting could cure. He didn't have anything to be cured. So, it didn't make the splash that he wanted it to make, but because it was reported in every newspaper in the United States, and most of the newspapers in Europe and even some in Africa and Asia, he got the message out, the idea out that fasting might just be curative. From that point on, that's really where we see this more scientific interest in fasting for health taking off in a way that it never had before, because it's fasting, and it's counterintuitive, and people don't want to do it. It was a very, very slow growth to get from there to where we are today. But without Henry Tanner, we wouldn't be where we are today.

Melanie Avalon: It sounds like social media. The first time, fasting was in the eye of the public and everybody was paying attention. So, he literally just sat on the stage?

Steve Hendricks: It was a very barren stage because they wanted to make sure that there wasn't any hidden food and that no one would sneak food into him. He had a cot, and he had a chair, and people could bring him reading material if it had been searched before. It got to the extent that if people were reaching up and shaking a hand with him, they would inspect his hands to make sure that there wasn't food being passed to him, being palmed off to him or something. So, yeah, he was just sitting there and talking with people for 40 days. Newspaper editor sent over teams of reporters to watch him for 24 hours a day. He also had his own core of watchers drawn from medical students and other doctors and so on. But yeah, he was just sitting there doing nothing but not eating.

Melanie Avalon: What was the significance of his show off with Dr. Hammond?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah. So, Dr. Hammond, who was a former Surgeon General of the United States, he was part of the occasion that gave Tanner the reason to go to New York to fast. Dr. Hammond was extremely skeptical of a group of women who were called the fasting maids. These were women who usually actually girls more than women, but young women and girls who had claimed a fasting power. They would claim that they could go months or in some cases, even years without eating or with barely eating. It was completely fraudulent. Not a bit of it was true. He had made it his mission to unmask these fasting maids. He'd even written a book doing his best to unmask them. It happened that there was one in Brooklyn in 1879, 1880, who had claimed to go, I forget forever, basically, with hardly eating anything. He had challenged her. Her name was Mollie Fancher to fast in public under the watchful eye of doctors round the clock. She said, "No." She could not be examined by male doctors. Her feminine honor would have been impugned and so on. That was the point at which Henry Tanner in Minneapolis, because all this was being reported in the newspapers around the country, Henry Tanner said, "Well, I'll come to New York and I will fast in her place."

Melanie Avalon: Gotcha.

Steve Hendricks: Oh, I'm sorry you asked. So, what became of the standoff? Well, eventually, Hammond had to admit that people could, in fact, go longer than he had ever expected without food. He still, of course, rightly thought that the fasting maids were a crock, but he had to revamp and revisit his ideas about just how people could survive in the absence of calories.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. Something I liked about that, like I called it a show off was, it felt like analogy for a theme throughout the history of fasting with conventional medicine and then, people positing this other idea of fasting because it seems you're talking about how Hammond was a very respected, conventional doctor and Tanner was of a different, I don't know what the word would be like woo-woo or alternative. [laughs] So, it seems like that was a theme throughout, especially later in the fasting history I think, there were so many forces against fasting.

Steve Hendricks: Yeah, emphatically. So, conventional doctors have always had a hard time accepting fasting. And even today, it's the rare conventional doctor who will look at the science.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. Why do you think if you had to pick one--? Well, you don't have to pick one. Why do you think that is?

Steve Hendricks: Sure. No, that's a great question. That's what I've been wrestling with for about 15 years. But I think the biggest reason is simply this. Fasting is premised on the idea that the body can heal itself. If we get out of its way, it knows what to do. Now, it's not a cure all. I'm not saying it's going to fix every single disease, but my goodness, it can reverse cardiovascular disease, and arthritis, and diabetes, and even one form of cancer at least. I could go down a list of 50 diseases that we have good evidence that prolonged fasting, in particular, can reverse. That is not something that doctors have been very good at hearing. Certainly, I make this case throughout history, there was a period even in the early 19th century, where the form of medicine that was most widely practiced by conventional doctors was called heroic medicine. It was horrible. The whole premise of it was, the doctor is going to be the hero. He's going to come in and save the day, and he's going to do this by bleeding the patient of-- leaders of his blood, of making him vomit, of making her have diarrhea with a purgative, of blistering the skin and all this that we're going to just whip the disease out of people. It undoubtedly killed more people than it helped.

That mentality, of course, doctors aren't doing that badly today, but they still have this mentality that disease is something that we have to conquer with technology, with our knowhow, with our fancy medical degrees, and all the stuff that we've learned in medical school, in our residencies and so on, and letting that go and saying, "You know what? If you just back off and monitor these people, make sure they stay healthy while they do their fasting, their bodies can actually do the healing without you." It's that without you part, that's very threatening to conventional doctors. I'll just close this little sermon by saying, "Look, I've gotten a lot of benefit out of Western medicine. I think conventional medicine has a lot of amazing points to it." So, I'm not trying to condemn all of conventional medicine. It has saved me more than once. However, this is an enormous oversight and I think that's where doctors fall down.

Melanie Avalon: I'm so glad you brought up the heroic medicine. I was saying in the beginning how I'd have moments where my jaw dropped open hearing the things that people would go through with that. And I just kept asking myself, it's like, why did people let these doctors do this to them? To that question, was it a cultural zeitgeist of just believing the system that these things were helping? Was it, ironically enough, the fact that because the body can heal itself that if people survive the heroic medicine and then the body healed themselves, then they would just credit the heroic medicine? How did this go on for so long? Relatively, recently, if you think about it, it wasn't that long ago that this was happening relative to humanity.

Steve Hendricks: True. Some iterations of this were continuing into the 20th century, for sure. Some of all of what you say, so, yes, every time you tortured someone who was sick and that person didn't die, well, gosh, if you were the doctor, you could claim that your heroic medicine saved them. The scientific method existed, but it was really rudimentary back then. And in the absence of any real science that was just impossible for people to prove. You could discount it. You could say, "Oh, I doubt that or something," but you couldn't prove that the heroic medicine had been more harmful than helpful.

I think the other piece of it that you hit on as well is, it is an extremely counterintuitive thing for people, all people, not just doctors to accept that, if we leave our body alone, it wants to heal itself. So, you find these accounts when you go back and look through the history of medicine, it doesn't matter where it is. It could be the US, it could be Germany, France, Russia. You find these accounts from 100, 200, 500 years ago where doctor writes something along the lines of, "It seems that if I leave my patients alone, some of them actually do better than when I give them the medicines." That was emphatically true back then. The medicines of the day were almost all quackery, unless, by luck, they happened onto some herbal remedy of some kind. They seemed to get better but here's the problem. When a patient is sick, they call me to their bedside and what they want is a cure. They want a pill. They want a potion. It's very much like today. They don't want to hear, "You know what? Go home and don't eat for three days and see if that makes your fever better."

It's an extremely hard thing for people to hear. You can understand why. When you have all the science, it just seems ridiculous. You want to just shake these people, but in the absence of the science, what people are left with are their own impressions. Well, what do we feel like when we don't eat? Well, we feel weak. Our minds quite often slow down. We're not able quite often to do the same amount of work as we did before. Everything in our own experience tells us that not eating does not make us feel better. So, I think when a doctor comes along and says, "Try this," it's an extremely hard thing to accept on both sides of that picture, both for the skeptical doctors who doubt this remedy and for patients who are equally skeptical throughout history.

Melanie Avalon: Chronologically, it's hard prescribing fasting for all the reasons that you just mentioned. And then, retroactively, if the person does heal, there're so many examples in the book where fasting won't even be credited. You talk about the woman at TrueNorth Health Clinic and her spontaneous remission, they wouldn't say it was the fasting that did it, it was just spontaneous remission. Or you talked about I think a study looking at-- I don't know if it was a study, but it was something looking at keto versus fasting mimicking diet and fasting for epilepsy. They didn't credit the fasting. They credit the diet aspects. So, even when fasting does work, it's like we can't give it the credit for what it did. But another thought that this made me think of was there were so many moments in the book where it was things I just took for granted that it had never occurred to me that people historically were not aware or saw things completely differently. So, for example, the idea that what we burn when we're fasting, could you talk a little bit about theories that people had about what we were running off of energy wise?

Steve Hendricks: Isn't that incredible? We all know that we run on our fat, at least for most of the time. Yeah, we burn a little bit of protein and so on, but it's basically our fat. But no, people didn't know that, even as late as Henry Tanner's days. So, again, we're talking 1880. There were scientific studies of nutrition and body composition and things like this. People debated endlessly what he was surviving on. Some of the theories were that the water that he was drinking had what were called [unintelligible [00:25:09], which was just these fancy words for just tiny, tiny organisms in his water, and that his body was surviving off of digesting those organisms. Other people believed that the air contained nutrients, and the more people who were around then the more nutrients were being-- In theory, the nutrients were expelled by people who were breathing them out of their bodies, and then other people could breathe them in. If you weren't eating, you could be nourished by breathing in these nutrients.

There was one person who accused Henry Tanner of doing this fast in New York, because there were millions of people there. So, far more people breathing into the air. Other people would claim-- Of course, fasting has mostly throughout history been used for religious purposes. So, people would claim divine assistance of some kind. That was, of course, the mechanism was never stated, but basically, you didn't need to eat because your stomach was filled by the Holy Ghost or Jesus or whoever it was you were crediting that too. So, yeah, it was quite a while, really, until the 20th century before science had settled the question of, what do you burn when you're not eating? You burn your fat.

Melanie Avalon: I think one of the other ones was like women burning their menstrual cycle or living off of that.

Steve Hendricks: Oh, right. [laughs]

Melanie Avalon: Crazy. Do you think if we had had the obesity epidemic earlier-- So, if people were overweight-- When people lose weight from fasting or calorie restriction today-- People can lose a lot of weight and you can clearly tell something left their body. So, it seems more obvious that you burned something away. But do you think because we didn't have obesity to the extent that we did today? it wasn't as noticeable that people were losing fat?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah, that's quite probable. Another piece of it is, in order to lose a whole bunch of fat, you have to fast for a very long time. Although, fasting has been around for a very long time throughout most of history, most people when they fasted were fasting for only a few days. There were a few people who fasted weeks or months, but they were very very rare. Even if you were obese, let's say, my height, 5'9", you weighed 300 pounds, you fast for three days, you're not going to notice any fat loss. It's going to be very, very subtle. So, I think that was a piece of it. And that also changed after Tanner's fast. Once people realized in the late 19th century, "Oh, my gosh, you can fast 40 days and survive." Then you got people who were doctors, who were occasionally fasting patients as long as 50, 60, 75 days. Then, of course, it would have been extremely noticeable at that point whether the person was overweight or not that they were losing their fat. But that didn't happen throughout most of history. So, that's probably a piece of it.

Melanie Avalon: You touched on this little bit just now with the types of fast that people were doing. You touched on it in the beginning about what was or was not true. So, something that really blew me away was, I think for most people, if they think about the history of fasting and what they think they know about it, there's just this idea like with the Greeks, for example. We think Hippocrates was all about, "Let food be thy medicine" and I guess, we can question if he even said that. But there is this idea that the old ancient people knew what they were doing, and the Greeks were fasting. Were the Greeks really fasting? What was happening there? What was the role of fraud in the history of fasting?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah. When I first started fasting, I was greatly relieved to hear that fasting was this ancient practice. If you're into fasting, you've all seen these quotes. Supposedly, Plato had written, "I fast for greater physical and mental efficiency." Plutarch said, "Instead of medicine, fast a day." Hippocrates said, "To eat when you were sick is to feed your sickness." There are all these quotations and stories out there. It turned out on examining them, it's one or two of which I had even related myself from what seemed like reliable sources when I first wrote about fasting a decade ago. When I dug deeper and really looked at the sources, it turns out, no, [chuckles] almost none of that-- All those quotations I just said, all bogus, every one of them.

Melanie Avalon: Crazy.

Steve Hendricks: Yeah. They're repeated. Some of them were created pretty recently within the last few decades, some of them-- There's a story about Pythagoras, who was made to fast before he became a student in Egypt, for 40 days. Didn't like it, but he did it, fell in love with it, and made all of his students fast for 40 days as well before they started studying with him. Well, it turns out that's not true. But it wasn't something that was developed yesterday. That was developed by people who were trying to glorify Pythagoras and associate him through the 40-day fast with the 40-day fasting of Elijah and Moses and whoever else. So, anyway, these stories are told for various reasons, but the reason they persist today is because they are extremely comforting to people who are doing this weird thing that, until very recently, no one else was doing. And so, they provide this sense of, "Oh, you are part of this long worthy tradition with these noble people who came up with mathematical theorems and so on." So, it must be a good thing.

In fact, the truth is, while it's true that we owe, probably, the first really deep signs anyway of therapeutic fasting to the ancient Greeks and to people around the time of Hippocrates, they had no idea what to do with it. They had no idea what to do with just about anything to do with medicine. The reason is because there was a taboo on dissecting bodies. So, you couldn't look inside the body, you couldn't see what was going on. So, they made up these cockamamie theories. And the one that eventually went out was called humoralism. It held that if you keep your body's four humors in balance, those were black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood, so they believed. If you kept them in balance, then you would be healthy. When they got out of balance, then you would be unhealthy. That's why you get to such things as like bleeding people is that's to try to get people's blood amount back in balance. Well, it was all completely nonsense, but all of medicine was based on that.

So, the few things that have come out about fasting from this time are just useless almost, almost all of them. So, for instance, a writer in the Hippo-- I should say, we don't know if Hippocrates wrote any of the works that are ascribed to him. There are about 60 works in the Hippocratic Corpus. They were probably mostly written by family disciples, whatever, some by imposters. Anyway, within the Hippocratic Corpus, one of these Hippocratic writers will say something like, when you have hiccups or you have muscle spasms, you should either fast or overeat. It's like, well, which one? Those are opposites. It was full of this nonsensical stuff. Now, all that being said, the Greeks did because they were open to fasting, the big contribution that Hippocrates and his colleagues made was that previously medicine was just seen as something that happened by divine fate or something. They said, "No, there are actual causes to diseases. We can learn to understand what those are and sometimes we may be able to treat them."

Now, the fact that their treatments ended up being wacky doesn't discredit this enormous advance they gave us. Because of that advance, people over the centuries started experimenting with fasting and eventually, they got around to just through random chance, practically stumbling on some things that did seem to work here and there. They weren't very prominent, they didn't last super long, but you could see these bubbling up of fasting intelligence over the years. One of the reasons I went into what you're calling the fasting fraud of these ancient quotations and stories and so on is because I just don't think they're so widespread, they're everywhere, they're on virtually every health website and anyone who talks about fasting usually resorts to one or two of them. What you find is, I don't think that helps us. What helps us is not covering ancient fasting in a glory that it doesn't deserve, but actually understanding where fasting came from, being humble about what things we did know and didn't know when as a species, and therefore, treating fasting with a lot more care, I hope.

Melanie Avalon: I feel like now I need to go through all my blogs and my book and my podcast. I'm sure I've been sharing some of this misinformation. This is just a random tangent. The thing you were saying about how the cure for, was it for hiccups? Was either to fast or to overeat? I actually was reading a study about fasting the other day. I was researching fasting's effect on pain because of that listener question for The Intermittent Fasting Podcast. I found a really interesting study and it was all about how both fasting and eating can relieve pain, super random tangent. So, maybe there was something with the hiccups. I don't know.

Steve Hendricks: Right. Well, there could have been something there. Had there been a more scientific way of parsing through the various evidence, something might have grown out of that, but they just didn't have that at the time.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. You mentioned it in the book, but when we're looking at these quotes, how do we figure out that these sentences weren't uttered by these people?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah, the first clue is, if someone's not offering a citation, don't trust them. [laughs] They may well be right. Of course, not everything has citations. But the simple thing to do is to go and look to see who is making those quotations with citations and then just keep following them back. You'll find that, I don't know, this quotation says, "Let food be like medicine, and medicine be like food" from Hippocrates, which you see everywhere. And no Hippocratic writer ever wrote that. What happens is, if you start chasing it back, one article will cite another article, which will cite another article, and often this is in the scholarly literature, but no one will be citing an ancient Greek source. Once you get back to the very earliest one of these, that's maybe in 1910 or maybe it's in 1842 or whatever, and you found that on Google Books or somewhere like that, if you go as far back as you can and there's nothing more beyond that, [laughs] then you have to conclude that it's probably made up.

You can check some of these by, if you want, emailing your favorite, I don't know, Hippocrates scholar and saying, "This quotation seems to be completely bogus. Are you familiar with this in any of the Hippocratic writings?" They'll usually be able to help you out in such a strait.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, it's so interesting. It speaks to a broader problem of that just happening in general, I imagine in the scientific literature. Because all it takes is some idea to slip into some journal somewhere and then that's quoted and then that's quoted and then we're lost with it. I think with the quote about how many topsoils generations we have left. I know there was something about that. Somebody said a quote about that at some conference without a citation, and then it made its way into some literature, and then it just kept getting quoted. But I imagine it happens with a lot of things.

Steve Hendricks: Yeah. Once it makes it into an academic publication, whether it's a peer-reviewed scientific journal or a book by an academic, forget it. Then everyone in the world will cite it and it's just a lost cause.

Melanie Avalon: Well, you mentioned 40 days a lot and I think probably a lot of people, when they think of 40-day fast, they might think of, "Jesus' 40-day fast." I was super fascinated by the history of fasting in different religions. Okay. So, to start here's a quote people will say all the time. They'll say that, "Fasting appears in every major religion." Does it appear in every major religion?

Steve Hendricks: It appears in almost every major religion. Now, you could split hairs over what's a major religion, but yes, in virtually every major religion. The one exception is Zoroastrianism, which is in Persia, modern day Iran. Zoroaster, the founder of Zoroastrianism, almost all religions experimented and some wildly adopted some form of asceticism just being really savage to your body. One form that was available to everyone was fasting. So, every religion, practically certainly every major religion that has evolved has had to wrestle with what is the place for asceticism in our religion. Zoroaster, after experimenting with it eventually decided that it was extremely harmful. He thought that fasting in particular would leave you too weak to farm, too weak to create productive and strong offspring. He chose a more hedonistic almost view of the world and said, "No, we're not going to fast."

What's curious about this is that, it's basically, well, as I say, a slightly hedonistic religion telling people that this is not a sin and that is not a sin, and you can do a bunch of things that these other religions won't. Well, today, Zoroastrianism has 200,000 followers and that's it in the entire world. Meanwhile, the religion, it mostly lost out to is Islam, which in some forms is very strict about what you can and can't do. There are a billion Muslims. So, I don't know, what the heck that says about, [laughs] human psychology. But that's a long way of saying that with the exception of Zoroastrianism, virtually all other religions, certainly the religions most of us have heard of had some place for fasting, but it varied enormously. Some places, some religions, it was a very small role and other religions, it practically took over the whole religion.

Melanie Avalon: Like in Hinduism, because I think that was one of the first religions you talked about that was primarily for enlightenment was the purpose of fasting?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah. The idea was that if you could eliminate desire, all right, you could reach nirvana. So, they would do all kinds of ascetic practices. They would deny themselves sleep, shelter, clothing, family. This is the first time you really get into really ascetic monks who are doing an almost athletic like training for the soul, one of the ways was fasting. This idea that it was a way of renouncing desire, which Hinduism at that time certainly saw as a holy path. Early Hinduism is one place where fasting just grew and grew and grew. And you can see how it happens. If a little bit of fasting makes you holy, then a whole lot of fasting, right?

Melanie Avalon: Really holy.

Steve Hendricks: Exactly. And that's exactly what happened. So, you eventually get to a point where there are Hindu calendars in ancient Hinduism that have 140 days of the year set aside for fasting. The sad part of it is, eventually, the men who ran the religion decided that the people most in need of fasting were women. So, the fasting burden fell very heavily on women, very lightly on men. It took a reaction many years later to tamp that down. But even today, if you speak to Hindu families and say, "Who in your family fasts?" You are much more likely to find women who fast than men do. And this is not an uncommon theme. This is exactly what happened in Christianity as well.

Melanie Avalon: No. So, I think this was my favorite theme in the book. I was blown away by how often it occurred and what happened when it occurred. So, even with the Greeks, I think you said that when there was fasting, it was more with women. That just never occurred to me. And then, I don't remember which culture or time it was, but there was one example where women could fast because it was the one thing they could do. Men would go on vagabond things and they could do all this other stuff, but the only thing women could do was like fast.

Steve Hendricks: Yeah. During the Middle Ages-- So, fasting really took hold in Christianity, probably 100, 200 years or so after the death of Jesus, who didn't have much at all to say about fasting like most Jews who fasted him, he surely fasted. But he didn't have much to do with it, early Christians didn't have much to do with it. But eventually, Christians decided that the church fathers who ran Christianity at the time that fasting could basically be used to subjugate women. The problem was that men were these very holy, devout creatures, but yeah, they were a little bit weak, and they were tempted by this temptress woman, who God had just put down here to torment than the male Christians was almost the view. The idea was that you could neutralize female sexuality by getting women to fast. Sexuality was important because by this time in Christianity, the sexual being had come to be seen as impure and tainting and so on.

Fasting was supposed to dry up the moist humors. Remember, the crazy humoralism we talked about earlier was predominating, dry up the moist humors in women that were supposed to behind female lust. If you took fasting far enough, it could obliterate womanhood. It could pare the hips, get rid of breasts and buttocks, it could end menstruation. This wasn't supposed to be a punishment. So, the church father said anyway, "This was supposed to be something to aim for to make yourself more holy, and your reward would be becoming a bride of Christ." This was quite literally meant some of the creepiest erotic writings of late antiquity.

Melanie Avalon: It's so creepy.

Steve Hendricks: Isn't it? Are these scenes where Christ is uniting with His virgin brides in the heavenly bridal chamber or something? It's just obscene. It's not to say that every woman in Christianity fasted herself to this near starvation, but that was certainly the ideal that was held out. By the time you get to the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the vast majority of saints who are women in the Catholic hierarchy, who have been sainted are these fasting saints. They have these very anorexic traits. Some of them literally starve themselves to death. Most of them just starve themselves into illness and probably an early death because of it though, of course, we can't say for sure. And so, that brings us to what you just referred to.

Devout Christians were supposed to be practicing some form of asceticism. It didn't have to be as crazy as what the saints were doing and so on, but it needed to be something. Lots of forms were open to men. One of the biggest ones of the day was called mendicancy, which is just going around homeless from town-to-town begging saying, "I'm a monk, I'm a brother of Christ. Please give me food or whatever." Your penance was to have or not penance, but your duty was to have a life with few possessions and to live on the goodness of others. When women tried that, there were a few who did. The most famous is known as Clare of Assisi, when she tried it, she was told, "Well, this homeless vagabonding is not in keeping with pure womanhood. So, get back into your abbey and forget this kind of thing." What was open to her was the power over her own body.

On the one hand, while it was a very misogynistic, very horrible set of doctrine that were being handed to girls and women throughout Europe of this time. On the other hand, some of them did this kind of reclaiming thing. "Well, okay, all you're going to give me is the power over my own body. I'm going to use it to starve my way to heaven," they would basically think. One theory, anyway, is to how you got so many of these fasting saints. There was just nothing else or very little else left over that they could do that would achieve for them the equivalent amount of holiness as the men were achieving through their asceticism.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, that was such a crazy, ironic dichotomy that on the one hand, fasting was used to really oppress these women, and repress their sexuality, and control them. And then, on the other hand, it was the one thing the women could do to assert themselves. It's so ironic. My sister came over the other night and I was telling her about the book, about all of this, and I was telling her about these saints who actually were probably anorexic and died from that, and then they were canonized as saints. I found the page in the book that you mentioned with those passages of the bride of Christ stuff and I was like, "You have to read this." It's fascinating. You talk about Catherine of Siena, who is one of the probably anorexic saints that died. You can still see her body, like parts of her body places?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah. There's this creepy thing in Catholicism where they have these in churches and cathedrals, these reliquaries and the relics that are in the reliquaries are often the body parts of saints. When a saint would die, sometimes it's a whole body, but people everywhere wanted a little bit of something. So, they might chop off a finger and send that to one town, chop off a foot and send that to another town. So, anyway, her body is scattered around Italy. Catherine of Siena was perhaps, no doubt about it, the greatest, most powerful fasting saint. She had an influence over the popes of the time, she had an influence over various princes, and so on, and their political dealings. She helped propagate one of the crusades that was happening in her era. She died very early, almost certainly because she had weakened herself too much through too much fasting.

So, she died in her early 30s. She died in Rome. She was from Siena and someone chopped off her head at some point and brought her head back to Siena. If you go into the Cathedral in Siena, you will see her head still there. You can google it. It's online. It's shocking how well preserved it is given that we're talking about something kind of forget the dates, but six or seven centuries ago. But yes, this creepy thing that is done in a lot of Catholic churches to take these various body parts.

Melanie Avalon: Do you think this theme-- Because I think we like to think that we're beyond this, but do you think this theme has continued with maybe not as much today with the Health at Every Size movement. Like Parisian fashion and runway models, is that like a continuation of that theme?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah, it's a very good question, Melanie and I'm not sure. I went into such detail about how fasting has been used to oppress women, because food and how much you should and shouldn't eat is, of course, still being used to just ruin women's lives, even if it's in a much more secular way of say, Paris Fashion Week than a dictum from the Roman Catholic Church. I don't know. I never found a scholarly article or report or something that drew a very clear line and said, "This is why we're having trouble today." The parallels to what was going on in the past and what is going on today with women's bodies were strong enough that I just wanted to lay that out there. You're astute to notice that to ask whether there's a connection. In the book, I don't say. I don’t say because I don't have answer. So, possibly yes, possibly no.

Regardless of whether there's a straight connection, I think we can learn from it. It's not a super sophisticated message here. It's just that women have been screwed over by usually men telling them what the hell to do with their bodies. I especially wanted to be sensitive to that, because I tell you, when I talk about, I mean, I've been talking about fasting with people for 15 years hands down. The ones who resisted far more, the gender that resisted are women more than men. Well, it definitely has to do with some of these themes, whether it's directly linked to what happened in history, who knows. But I think we need to recognize that and understand it and be sympathetic to it.

Melanie Avalon: It's such a complex and complicated topic and you talking about women being resistant to fasting. I definitely see it especially with The Intermittent Fasting Podcast and all the questions we get. Because there are a lot of studies on the science of the health benefits of fasting, particularly in women, and particularly for hormonal issues, PCOS, a lot of benefits that can be had. But there's also a huge concern that women shouldn't be fasting. It's hard to piece out how much of that is from themes we all just talked about, about societal issues of women and eating or how much it's just that women might tend to over restrict and be too restrictive in diet and lifestyle and fasting. I don't know, it's just a very complex topic. So, another reason I love your book so much, I hadn't considered the history of fasting in women at all as a piece in it. So, it's really interesting.

Steve Hendricks: Yeah, I would love it if someone could come up with an answer to that question. Hopefully, some scholar will turn to that someday.

Melanie Avalon: Another religion that was super interesting. Jainism. What happens with fasting there and there suicide fasting?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah, it's really something. So, Jainism probably took fasting to an even greater extreme than Christianity did. So, Jainism, certainly at that time, the belief Jainism, Hinduism, and Buddhism, all grew out of the same. They're called Vedic religions in ancient India. They interpreted them different ways and often in reaction to each other and partly because Hinduism, even as crazy as it was with fasting, and Buddhism, which was much more moderate with fasting, because they were both on the slightly more moderate side than Jainism. Jainism reacted by taking fasting to quite an extreme. And they took a lot of dogma to extreme. Their main view is that life is either suffering or it's causing suffering. Even grass is alive. So, if you walk across the grass, you're causing suffering. The problem with that is that all organisms are composed of karma, which they've conceived of as these literal bits like atoms.

Your karma are mostly bad deeds and they keep the soul from soaring to heaven. They literally weigh your soul down, so that it can't soar to heaven. Fasting, they decided burned off bad karma. So, they would take fasting to some very extreme practices. One of them was this year long thing that they called Varshitap, which If I remember it correctly, you eat nothing from sunrise until sunset, 36 hours later. Then you eat after sunset. Once you've done that, you start all over again at sunrise, fast another 36 hours till sunset, eat a little more, do it again at sunrise. You do this for an entire year, which is just insane. So, they had all these practices.

But the one that has gotten the most attention is this suicidal one you referred to that was called Sallekhana. And Sallekhana was simply starvation unto death. The original idea was that if you were as enlightened as you could possibly be, you had nothing more to achieve in this life. You had burned off as much karma as you could, well, what was the point in continuing to live? If you continue to live you might just rack up some more bad karma, you might inflict suffering, so you could starve yourself to death. Very, very devout Jains did this. We don't have an idea as to how many people did this over time. We're not talking millions here. We're talking probably-- Well, today, we think that there are probably a couple of hundred people a year who are doing this.

Now, in modern times, it's been modified somewhat. So, you don't have to be near enlightenment and so on, if you have a terminal illness. You've got a terminal diagnosis, there's no hope for you, you can starve yourself to death rather than suffering. There are cases in the West, of course, not just in Jainism, where people have done this, not a ton, but a few who-- I speak of a writer, Sue Hubbell, who in 2018 got a dementia diagnosis and it was getting worse and worse and worse, and she essentially practiced Sallekhana. She starved herself to death for about 34 days. So, people report that this is not a completely painless death, but it is much more painless than many other ways to go and that the pain is very manageable and that all in all it's kind of a peaceful death. So, who knows. I don't have much else to say in favor of Jainism, but it seems like an interesting thing to consider for those who are terminally ill.

Melanie Avalon: Jainism, when I was reading about it, literally, it sounds like the definition of you just can't win. You just can't win, if you are-- [giggles] Everything you do is not good. How do you think that compares to somebody dying on their deathbed and then they stop eating and that's how they die? That seems to be very common or more common.

Steve Hendricks: Yeah. There's quite often in the last stages of death. If you have a cancer or something, then it's just one of these lingering things where you've been dying of the cancer for six months. Quite often in the last two days, three days, seven days, maybe you'll just lose your appetite and that's your body shutting down and basically preparing for death as I have had it explained to me anyway, and I think that makes sense. This is a different category of thing. I have cancer. It's a terminal diagnosis. I could linger for six months and deal with the pain, the medication, the whatever else, or I could starve myself to death and be dead in 30 days. In the Sue Hubbell's case, she had dementia. Heck, she was only, I think, in her 60s. She might have lived another 25 years. So, the difference is it's consciously seizing the opportunity to shorten that period of what for a lot of people would be hell.

Melanie Avalon: Something I would love to know. I've never thought about this. I'd be super curious, because we know of all of the processes that are activated by fasting, and cellular renewal, and all of the benefits. When a person is on their deathbed and they do enter that state where their body is shutting down and they stop eating, I wonder if they still activate all those processes or if it's different?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah, that would be really interesting to know, because the reason that most of us, well, many of us fast is because it initiates all these repair mechanisms. If your body has some inkling, I assume, that it's going to die-- [crosstalk]

Melanie Avalon: Like knows.

Steve Hendricks: Right. Would it bother with the repairs? I have no idea. I don't think it's ever been studied anywhere.

Melanie Avalon: It would be a sad and a morbid study. I would be very curious though. Just before we leave the religious aspect, because I think people, especially since Christian is such a large religion, they might have been surprised to hear that fasting wasn't as prominent or as big as a part as maybe we have thought it might have been, especially with Jesus in the 40-day fast and everything. I think when Jesus talks about fasting, He talks more about doing it in private rather than public. So, Lent, what's going on there?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah. So, that's a really good question. What happened was after Jesus, what we think is a pretty good record of what He probably said. But He didn't lay out how to build an entire society and how to do everything. The church fathers had to come up with a lot of doctrine. Although, the early church fathers heeded Jesus. Jesus had come and basically said, "All these silly dietary laws and everything else that the Jews are doing, you don't need to mess with that. Just do unto others as you would have them do unto you. If you obey that golden rule, then the rest will fall into place. Just don't get bogged down with 3,000 laws." One of those things that people assume that He was talking about was don't get bogged down with fasting. So, in the first century or so after His death, there was not much fasting in Christianity. Some of them-- they had been, many of them, most of them probably Jews, Jews fasted. So, they probably done some fasting and so on.

What happened was that the church fathers found that they could make fasting into something extremely useful to them. I've discussed the importance of subjugating women in order to keep them in their place and not tempt men. It wasn't all just that. That was a huge part of what was going on. But there was also, for instance, there came to be an idea that evolved a century or two after Jesus' death that was called the BIOS Angelicos, the Life of the Angels. The idea was that you should try to be on Earth as much as you would be when you become an angel, or a deceased, or whatever they thought they would be in heaven. And angels were obviously incorporeal. They didn't have bodies, so they didn't eat.

To the extent that you were able to model that here on Earth by not eating, by starving yourself, you could achieve this life of the angels here on Earth or as close to it as you could possibly get. So, for reasons like this, fasting took on a life of its own, and it just grew. Most people probably heard of the desert fathers and desert mothers, these monks in antiquity who would go out into the desert and do all these kinds of ascetic feats. One of their ascetic feats was to fast for days or weeks or months. And so, fasting gained a momentum of its own. Remember how I said before that in Hinduism there were eventually as many as 140 days or something like that of fasting on Hindu calendars. On Christian calendars, it expanded so much by the Middle Ages and Renaissance, some places in Europe had 220 or 240 days of fasting throughout the year. It was just overwhelming how it grew to this proportion.

Lent grew from that sort of just same general expansion. It had eventually been-- Easter originally was the holiest day of the Christian calendar. It was also the saddest. It was occasioned for mourning because Christ had been killed, He'd come down to save us. And then there was the joyous resurrection. So, it ended joyfully, but it was a very mournful period. People found and-- The church fathers found that if you wanted to emphasize to people just how mournful they should be, how sober and how contemplative that they should be, you should make them fast. Easter got preceded by depending upon where this was enacted a day, maybe two days, eventually, maybe three or four days or a week of fasting, which eventually, over time, because again, same thing as what we're talking about with the Hindus and the Jains of a little fasting makes you holy, a lot of fasting makes you holier. So, it eventually grew to this 40-day famine before Easter and it was honored in different ways.

Some people just famously, as we know today, they just give up one thing. More commonly, it was or I should say more commonly among the more devout, it was a partial day of fasting each day. So, you might fast until 03:00 PM in the afternoon, have a light meal, maybe a dinner, and then you would do it all over again the next day. It wasn't 40 days without food for most people. So, that's how Lent grew. It was the way that fasting tended to grow throughout the more primitive parts of human history, which is just this simple idea of, "Well, gosh, maybe more fasting is even better for us."

Melanie Avalon: Those fasting days like you mentioned in Lent, were those the type of fasting days like in Hinduism, when they would have all those days on the calendar? Were they complete fast or were they just eating lightly?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah. So, for most of those, when I say 220 or 240 days on some of these medieval European calendars, most people observe those by eating lightly. Some people would just observe them by giving up desserts or maybe they would give up meat. So, it was a partial fast for most people. For the most devout people who really honored it, they tended to give up all food until mid-afternoon and then they tended to eat lightly for the rest of the day. One would assume they gorged the next non-fasting day that they had in order to make up the calories, because otherwise they would have been in quite a caloric deficit, but that seems to be what happened.

Melanie Avalon: Little ADF action going on?

Steve Hendricks: Right. Something like that.

Melanie Avalon: I think when people think back through the history of Christianity, they think of the moment of challenging all of this dogma and doctrines would be with Martin Luther and the Reformation. So, did that affect fasting in any way?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah, absolutely it did. But it probably wasn't as big a deal with Martin Luther as people thought when he nailed his, well, he probably didn't. Another myth of history, yeah, he didn't nail his theses to the door of the church. But when he published his theses, he was upset about fasting. At that time, what had happened was, at the same time that there was this one poll of fasting, which was this crazy, over the top, extreme fasting that led to the fasting saints and some of the stuff we've talked about. There was also this other poll in which ordinary people were trying desperately to get out of fasting anyway they could, because they hated it, particularly, if it's on the calendar a couple hundred days a year. So, the church had eventually gotten around to letting the rich buy their way out of fasting by making donations to the church. These were called dispensations. You could buy a dispensation to let you drink milk, or eat butter, or something during your days when you were supposed to be fasting.

There's even one of the cathedrals in France in Normandy has a Butter Tower. It's called the Butter Tower because this gorgeous Gothic tower was built on the money from the dispensations for lay people to eat butter during Lent and other fasting days. So, Martin Luther didn't like all that, but he didn't make a huge deal out of it right there and then in his original protests. But he eventually became much more vocal as he was criticizing the pope in Rome and other members of the hierarchy of the church. He eventually went after them for these dispensations. Not only were they unfair to people who couldn't afford them, but who were these humans in Rome to be selling off something that was supposedly God's right to tell us to do or not to do? And so, from there in the Reformation, fasting played a pretty large role in getting people to revolt against the church, because fasting was something that was hated, the church was corrupt, it had tons of money, and rich people could get out of it. So, you had a lot of very ordinary people who were very primed by fasting to revolt against the church, which eventually led to the establishment of all these Protestant churches and countries across Europe.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. One of themes I found so interesting is the backlash and the responses surrounding fasting, and especially politically or even with the government and things like that. Like in the US, there was quite a few interesting people. I was wondering if we could talk about Bernarr Macfadden. I was so fascinated by him. What he did and this idea of the cult of the Body Beautiful and everything that happened with him, so how does he relate to the fasting world?

Steve Hendricks: Bernarr Macfadden stumbles onto the scene about 20 years after Henry Tanner's fast in 1880. Macfadden was perhaps one of the greatest showmen in America. I don't mean that literally. Well, he did do some shows on stage, but just as a carnival like media figure. He came along and in 1899 established a journal called physical culture, which by the time it was done with its first year had 100,000 subscribers, which made it one of the biggest subscribe journals in the country and would just keep growing and growing. I think the number between the two World Wars was that it sold 50 million copies.

What physical culture was this Body Beautiful magazine. It showed people who exercised, exercise wasn't huge back then, and lifted weights, which was even less huge. He would show them what they could make of their own bodies. And that was its power. It was like, everyone has the power to be as beautiful and handsome as these models, who, not incidentally, he showed wearing next to nothing. Sometimes, wearing absolutely nothing, but with the genitals artfully concealed behind a literal fig leaf or something. So, he gained this enormous, enormous following. He created one publication after another. It was kind of the beginning of this confessional, first person lurid stories that played fast and loose with the true form of journalism or so-called journalism. Some of his other publications were like True Detective, True Romance and stuff. Supposedly, the stories were true, but of course, they weren't.

At the height of his powers with all of his journals and he owned a newspaper too. He had a circulation of 200 million copies a year in a country that didn't have anywhere near the number of people who we have today, of course. But he made all kinds of fantastic health claims. He had a way of regrowing bald heads, regrowing the hair on the heads. He had a way of, one of the most famous was the thing that he called the penis scope, which was this like glass tube and a vacuum pump, and it was supposed to give these middle-aged men with erectile dysfunctions like firmer erections. It is just crazy, quackery, non-sense stuff, right? But in the midst of all this, he also put out some really useful information about fasting, because he had discovered fasting when he was a child, probably had heard about Tanner's fasts and so on, but he had noticed working on a farm that farm animals, when they got sick stopped eating.

One time when he got pneumonia, he tried it and believed that it had helped him. He did all of these very important things, but very poorly respected things because of who he was to promote fasting. So, he wrote books and there were articles in his magazines about fasting, and he supported various fasting doctors and so on. It didn't take, because he was such a quack on so many other things that the medical establishment absolutely wanted nothing to do with him and he just blasted them left, right, and center in his publications, but it had so very little effect. What he did do, however, was to carry forward, not just carry forward, but expand on Henry Tanner's bringing fasting to the public consciousness, because what Macfadden did was, he actually showed, I'm not talking it in any scientific way, but he would report cases of people who claim to have been cured of their diseases by fasting. So, people who had skin diseases, headache, constipation, kidney diseases, on and on and on, it's a very long list. And this sparked the curiosity of a very small number of doctors, and scientists, and more judicious reporters than he was, who took fasting to the next step. But he's an enormously important transition figure.

Melanie Avalon: So, fascinating. It just makes you realize you just don't know what's going to have an effect. I'm blown away. You said 200 million copies a year?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah.

Melanie Avalon: Today, there's only like 300 million, I think, citizens?

Steve Hendricks: Yeah. We've got, I don’t know, 330 and 340 million people here. So, yeah. One person might be getting five of his journals. It's not like it was going to 200 million people. That figure was in 1929 before the Great Depression struck. He went downhill from there. But even as late as, oh, I forget what the year was, early 1950s let's say, there was this famous TV show, where you had to guess a famous person based on just a sentence that they read or something like that. I'm forgetting what the name of it was. It was really catchy. But anyway, 30 years after his peak, 20 years at least, he could appear on this TV show without his face showing, just his voice reading one line or whatever it was, and people could guess who he was. He had that much influence over the culture.

Melanie Avalon: And he started his own religion?

Steve Hendricks: [laughs] He did. He started and had to be one of the shortest-lived religions in history. He started something called Cosmotarianism. Cosmotarianism was just a blend of Macfadden health doctrine and kind of some parts he had stolen from Christianity. It must have lasted six months or something.

Melanie Avalon: Speaking of Cosmo, I learned about-- I guess, Cosmopolitan magazine used to be different than it is today.

Steve Hendricks: Indeed. It was a serious journal that talked about, I don't know, gosh, the economy, or the state of the French Army, or what have you. It was not a sex tips and blemish free skin kind of journal.

Melanie Avalon: There's another theme there that I think we see today. Not specifically fasting, but even today, you just don't know what's going to take off, what's going to become popular. Even with people who might have celebrity attached to them, you don't know if what they promote will be successful. So, I was super interested to learn that. Like Upton Sinclair, for example, who most people have heard of and familiar with that he wrote about fasting.

Steve Hendricks: Yeah. He was really the next, I think, most important person after Macfadden. So, Upton Sinclair is the famous muckraking journalist, when he was in his late 20s wrote a book called The Jungle and it was about the atrocious treatment of workers in Chicago meatpacking plants, and also about the completely unsanitary conditions there. But he had a much lesser-known side to him. And that was that he wrote a book called The Fasting Cure, which grew out of a couple of long articles that he had written for Cosmopolitan magazine back in 1910 and 1911. Sinclair had a story about, like a lot of people who come to fasting, which is, "I had all these illnesses. I couldn't shake them. I went to doctor after doctor after doctor." He spent, gosh, I think translated into today's money, something like $500,000 on doctors, and sanitariums, and retreats, and so on trying to cure himself of what sounds like a really unshakable fatigue, constantly upset stomach, headaches that would strike him out of nowhere and no one had any cure.

Then he stumbles on some of this crazy stuff from Bernarr Macfadden and he tries fasting. To make a long story short, it cures him. All of his ailments go away. He is able to write more prolifically than ever and he says, "Well, I got to tell the world about this. I've got a platform. So, let's get the news out." And so, what he did that was very very useful. In addition to writing these two articles for Cosmopolitan, he also put out a survey, I think it was at the end of one article and said, "Hey, if you have fasted, if you're reading this, would you please write and tell me whether you had a good response, bad response? Tell me if you were fasting to cure something. Did you cure whatever it was?" So, he did the first really systemic attempt. He's a layperson. He's not a scientist. He's publishing in something like ordinary people need to be able to read or his publisher will not sell it.

He did, as good as a layperson could do, a very good job of assembling a whole bunch of case studies of people who said, "Yeah, I had a stomach ulcer. I fasted for 35 days, it went away." Or, "Yeah, I had thus and such wrong with my liver or thus and such had a carbuncle on my toe. And after a fast of 20 days, it went away." And so, what he was doing was he was saying, "Look, you don't have to take my word for it." He provided the names and addresses of these or at least the cities that they lived in, which back then was good enough. He would provide information about these people and just say, "I just want men of science--" They were almost all men back then, of course. "I just want men of science to look at this seriously. It surely cannot be that we have all this evidence of all these people more than 100, 90% of them who said they got better when they fasted."

It surely cannot be that we have all this evidence and scientists will not take a look at it, particularly because at that time, medicine could not cure most diseases. It was really still a very impotent form of medicine back then. But of course, as you might have guessed that did not happen. Scientists generally looked away. Most men in medicine looked away.

Melanie Avalon: That's something I found so interesting. When they really first started studying fasting for longevity and it was a lot in rodent studies, I think probably in the 1980s, I think you made a comment about how there was all this really fascinating research on longevity, and telomeres, and shrinking organs, and nuclei, and stuff. But it took so long for people to apply that to humans, like to do human studies. Why do you think that is?