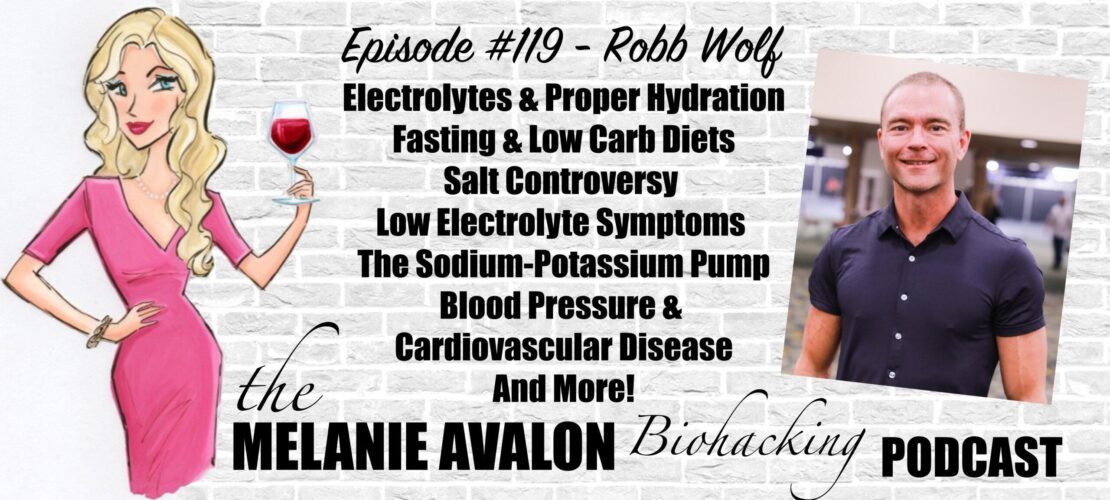

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #119 - Robb Wolf

Robb Wolf, is a former research biochemist and 2X New York Times/Wall Street Journal Best-selling author of The Paleo Solution and Wired To Eat. He and co-author Diana Rodgers recently released their book, Sacred Cow, which explains why well-raised meat is good for us and good for the planet. Robb has transformed the lives of hundreds of thousands of people around the world via his top-ranked Itunes podcast, books and seminars. He’s known for his direct approach and ability to distill and synthesize information to make the complicated stuff easier to understand.

Robb co-founded the 1st and 4th CrossFit affiliate gyms in the world, he holds a brown belt in Brasilain Jiu Jitsu, is a former California State Powerlifting champion and as part of the Discovery Channel’s “I-CaveMan” series, Robb took down a 650lb elk with an Atlatl (a hand thrown spear).

LEARN MORE AT:

robbwolf.com

Sodiumdrinklmnt.com

SHOWNOTES

For A Limited Time Go To drinklmnt.com/melanieavalon To Get A Sample Pack For Only The Price Of Shipping!

2:35 - IF Biohackers: Intermittent Fasting + Real Foods + ife: Join Melanie's Facebook Group For A Weekly Episode GIVEAWAY, And To Discuss And Learn About All Things Biohacking! All Conversations Welcome!

2:50 - Follow Melanie On Instagram To See The Latest Moments, Products, And #AllTheThings! @MelanieAvalon

Stay Up To Date With All The News And Pre-Order Info About Melanie's New Serrapeptase Supplement At melanieavalon.com/serrapeptase!

4:55 - FOOD SENSE GUIDE: Get Melanie's App To Tackle Your Food Sensitivities! Food Sense Includes A Searchable Catalogue Of 300+ Foods, Revealing Their Gluten, FODMAP, Lectin, Histamine, Amine, Glutamate, Oxalate, Salicylate, Sulfite, And Thiol Status. Food Sense Also Includes Compound Overviews, Reactions To Look For, Lists Of Foods High And Low In Them, The Ability To Create Your Own Personal Lists, And More!

5:50 - BEAUTYCOUNTER: Non-Toxic Beauty Products Tested For Heavy Metals, Which Support Skin Health And Look Amazing! Shop At Beautycounter.Com/MelanieAvalon For Something Magical! For Exclusive Offers And Discounts, And More On The Science Of Skincare, Get On Melanie's Private Beautycounter Email List At MelanieAvalon.Com/CleanBeauty! Find Your Perfect Beautycounter Products With Melanie's Quiz: Melanieavalon.Com/Beautycounterquiz

Join Melanie's Facebook Group Clean Beauty And Safe Skincare With Melanie Avalon To Discuss And Learn About All The Things Clean Beauty, Beautycounter And Safe Skincare!

The Paleo Solution: The Original Human Diet

Sacred Cow: The Case for (Better) Meat: Why Well-Raised Meat Is Good for You and Good for the Planet

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #57 - Robb Wolf

12:15 - How Did Robb Get Into Electrolytes?

14:15 - pairing high intensity sports with low carb eating

17:30 - keto-aid

19:35 - the Natriuresis of fasting

24:05 - LMNT: For Fasting Or Low-Carb Diets Electrolytes Are Key For Relieving Hunger, Cramps, Headaches, Tiredness, And Dizziness. With No Sugar, Artificial Ingredients, Coloring, And Only 2 Grams Of Carbs Per Packet, Try LMNT For Complete And Total Hydration. For A Limited Time Go To drinklmnt.com/melanieavalon To Get A Sample Pack For Only The Price Of Shipping!

26:50 - how much sodium did hunter gathers get?

28:00 - sodium concentrations in intracellular fluid

29:00 - Hypernatremia

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #100 - Dr. Que Collins

30:35 - internal water creation

31:00 - hunter gatherer sodium intake compared to modern day intake

31:35 - our taste for salt

32:25 - the combination of electrolytes vs individual electrolytes

33:10 - calcium

33:30 - magnesium

33:55 - sodium and Potassium

34:35 - the sodium-potassium pump

35:10 - diabetes and hypertension

36:00 - hormonal signaling to pull sodium out of the bones

36:50 - the original gatorade

37:30 - sugar in electrolyte drinks

38:20 - the cotransporters of sodium uptake

39:15 - medically supervised fasts

42:10 - catabolizing of protein

Longevity: are we trying too hard?

44:05 - over-fasting

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #115 - Valter Longo, Ph.D.

45:20 - Stem cells to Senescent cells to cancer

48:30 - fasting research

50:00 - highly processed foods and calorie restriction

52:25 - stem Cells Glycolytic needs and ketogenic diets

Dr. Bernstein’s Diabetes Solution

56:30 - a 5-6 hour feeding window

57:30 - the downside of fasting

59:15 - being metabolically flexible

1:00:10 - inaccuracy in rat studies

1:02:45 - INSIDE TRACKER: Get The Blood And DNA Tests You Need To Be Testing, Personalized Dietary Recommendations, An Online Portal To Analyze Your Bloodwork, Find Out Your True "Inner Age," And More! Listen To My Interview With The Founder Gil Blander At Melanieavalon.Com/Insidetracker! Go To Insidetracker.com/melanie And Use The Coupon Code MELANIE30 For 30% Off All Tests Sitewide!

1:05:15 - the salt debate

1:06:15 - cardiovascular disease

1:08:45 - low sodium diets

1:10:05 - low sodium stress

1:11:05 - genetics vs diet: causes of high blood pressure

1:13:10 - the role of race in high blood pressure with low sodium diets

1:17:00 - LP-IR score and genetic risk

1:21:00 - intuitive intake of electrolytes

1:22:50 - the signs and symptoms of low electrolyte status

1:24:00 - the change in the taste of salt

1:25:10 - does the homeostatic baseline change for sodium? is there a minimum effective dose?

1:29:45 - Appropriate hydration

For A Limited Time Go To drinklmnt.com/melanieavalon To Get A Sample Pack For Only The Price Of Shipping!

1:33:30 - new flavors!

TRANSCRIPT

Melanie Avalon: Hi, friends, welcome back to the show. I am so incredibly excited about the conversation that I'm about to have. This is a true statement, when I say that I have had over 100 guests, all incredible guests on this show, but today's guest is my favorite guest out of all of them. I have done one episode before with this fabulous human being, but I will retell briefly my story about everything. Basically, the reason or a foundational reason that I became obsessed with the whole holistic health movement and the power of how our food affects our biology and our constitution was because I read a book called The Paleo Solution. I did not anticipate that that book would change my life, but it honestly really, really did. I don't even have it anymore because I lent it out and never got it back. But basically, that book was written by the fabulous Robb Wolf. I became obsessed with his work. At the time, it was called The Paleo Solution Podcast, I would listen to every single episode. Now it's called Healthy Rebellion Radio, for listeners who would like to listen now.

After The Paleo Solution, Robb released Wired to Eat, which was all about how you react to different foods and different carb intakes, which is really eye opening. I really, really recommend that book as well. And then most recently, he released Sacred Cow, which I find myself recommending that book all the time, if you want to really get a nuanced, comprehensive view of really the implications of animal husbandry and how animals affect the environment, it's mind blowing, it's very eye opening. The last episode we did we really dived deep into it, so I'll put a link to that in the show notes. I was actually interviewing Gary Taubes recently for his new book and at the end, he was saying that basically his one concern with the keto, low-carb diet is the effect on the environment, and I was like, “Have you read Sacred Cow? So, I basically just threw it at everybody?

Robb Wolf: The answer to that is, “No, he hasn't.” Gary and I have gone around and around on this topic. Yeah.

Melanie Avalon: He was like, “I read parts of it.” I was like, “Well, read all of it, please, and report back.” So, yeah, basically, I just-- I'm forever grateful to your work, Robb. The topic of today's show is electrolytes, and that is because Robb Wolf has an incredible product called LMNT. It's an electrolyte supplement. Well, I've been promoting it to my audience, and I have been getting so much incredible feedback, especially from people who do low-carb diets, keto diets, fasting, and the profound effect that taking electrolytes, specifically LMNT has had on their health and their experience of their diet and issues they might have been having. On top of that, I've been getting so many questions about electrolytes. So, I figured it was time to just have a conversation about all of this. So, that was really, really long. Robb, thank you so much for being here.

Robb Wolf: Huge honor to be here. I am so honored and tickled that I've had some influence on your amazing impact in this health and wellness space. It makes doing this very much worthwhile knowing that I've had some impact there. So, thank you.

Melanie Avalon: Yes, majorly. I am just forever grateful. Listeners are probably ridiculously familiar with you, but for those who are not, you are a former research biochemist. Those books I mentioned the first two are New York Times and Wall Street Journal bestselling books. And you actually co-founded the first and fourth CrossFit affiliate gyms in the world, which is a really cool fun fact. But in any case, so to get into today's conversation. I've so, so many questions, but I guess a good place to start is, I'm really, really curious. So, you have LMNT a product line now, what was the inciting incident for deciding to focus on electrolytes? Did you have an epiphany one day? Was it a slow realization? What led to where you are now with promoting the importance of electrolytes?

Robb Wolf: Oh, man, it's a really good question. The genesis story is interesting, and even though, I'm pretty good at the biochemistry, the metabolic pathways around ketogenic diets and human performance metabolism at large, but you never know everything. Backing up a little bit more, 23 years ago, I was super sick from ulcerative colitis, I was bound to-- I'm about 165 pounds, reasonably good shape for getting to be old dude, but I was down to 125 pounds from my ulcerative colitis because I just was absorbing nothing that I ate, and at that time I was eating a low-fat vegan diet, which I think can work for some folks, it absolutely does not work for me. I was pretty much at desperation point and through a long series of circumstances, this idea of a low-carb paleo ancestral-type diet got on my radar, and I tried that. For me, it was a lifesaver.

We fast forward 23 years later, I do really well in most things, eating a lower carb diet, particularly my gut health and blood sugar regulation. I've tried reintroducing carbs in a variety of ways and safe starch and all this stuff. And, man, for me it really doesn't work all that well. I know for some people, reintroduction of carbs goes great, for some people it doesn't. But I've also always throughout most of my life have been interested in things like CrossFit and Muay Thai and Brazilian Jujitsu, which are all very glycolytic energy demanding activities. Historically, a low-carb diet is really tough to pair with these super high intensity glycolytic type sports or activities. I had struggled for years trying to figure out how do I eat in a way, so that I feel good day to day, but then I have the energy to do the activities I want to do? And so I tried carb cycling and pre and post workout, carbs and different things like that, and it worked okay, but none of it was really that great.

I started-- continued poking around, looking around online for people that were low carb, but also doing Brazilian jujitsu. I noticed that there were a number of women who were competing at a high level in jujitsu, and their profiles it would say, like Keto Mama Jujitsu 119 or whatever. And I'm like, “Oh, okay.” I started looking at this stuff, and they were all following this program called Ketogains. I started kind of poking around that scene and the two guys that founded that, Tyler Cartwright and Luis Villasenor struck me as really reasonable people very, very smart, very dedicated to the folks that they work with, they do these multiple times per year, online bootcamps where they focus on appropriate protein, low carb, kind of ketogenic diet with smart strength training and a lot of community support and whatnot. They just had stunning results with weight loss and with health improvements with people. So, I stalked these guys and started hanging out with them, manage to bamboozle them into being a speaker at one of their first in-person events.

I do what most people should do when they're interacting with someone who's very good at something, I asked them to assess what I'm up to and figure out if there was a way that I could better fuel my activities, and they looked at everything I was doing, and they're like, “You look pretty good. But I suspect that you're not getting enough electrolytes, specifically sodium.” What I did was I ignored their advice at first. I'm like, “Oh, no, no, I salt my food. I'm not afraid of sodium.” And they're very patient people and so probably a good year went along, and we started working together on a bunch of different projects, like we worked on a health initiative for the Chickasaw Nation and a bunch of really cool things. But I kept whining and complaining about my jujitsu performance and not really recovering from activity and whatnot. They would say, “Hey, I really think those electrolytes were important you know.” [laughs]

Finally, one day they were like, “No, man, really. Listen. Do us this favor. Weigh and measure everything you're eating including your electrolytes, like everything you're adding to your food, when you add some salt, measure it, weigh it, add it into something like Cronometer, which tells you the protein, carbs, fat, but also like the sodium, potassium, magnesium, calcium, it gives you a very comprehensive picture of what's going on. And let's see where your electrolytes are, especially sodium.” I was less than half of what they were recommending on sodium. I bumped that up. They had this thing that they called KetoAide, which was some regular table salt, some potassium chloride, which goes by the brand name, NoSalt, and some magnesium citrate, some lemon juice, some stevia, shake it up, drink it, and I felt amazing. It was literally like a light switch was flipped. When you think about the fact that every thought we have, every muscle impulse that we create, is driven by sodium potassium pumps. If your electrolytes are off, it's going to dramatically affect the way that you look, feel, and perform.

Just as an example, when somebody ends up in the emergency room, the very first things that doctors look at is their pH and their electrolytes because if your pH is off one way or the other, you can get very, very sick or you can die. If your electrolytes are off one way or the other, you can get very, very sick and you can die. And so, like pH and electrolytes are arguably the most tightly regulated physiological parameters in our whole system. Once I figured this out, I was like, “Guys, electrolytes are super important.” They're like, “Yeah, I know, we've been telling people this for like, 10 years.” [laughs] This is where even if you individually are regarded as an expert on a topic, it's really good to shut up and just listen to other people around you [laughs] because I could have saved myself another year of struggling.

And what's interesting I guess in this I know I'm just wandering all over the place, but if somebody is put on a medically supervised ketogenic diet, say like for epilepsy, their dietitian will make certain that the person gets at least five grams of sodium per day, by hook or by crook, whether it's pickles, or chicken bouillon cubes, or whatever it is, because there's a really clear understanding that when people eat a low-carb diet, their insulin levels decrease, which causes them to decrease a hormone called aldosterone. Aldosterone causes us to retain sodium. There's this phenomenon called the natiuresis of fasting when people are in a low-carb state, or they're fasting, they lose water and sodium like crazy. And if you don't replenish that, people will be super lethargic, lightheaded, they have high heart rate, their sleep is disturbed. This can lead into thyroid issues and things that we'd like to call adrenal fatigue and whatnot. This was really the genesis of this whole idea. But we didn't have this idea initially of making a product.

What we did is, we made a free downloadable guide for how to make this KetoAide product. Within about six months, we had over a half million downloads of this thing. People were just going crazy. They're like, “The KetoAide is amazing. Thank you so much.” But when I traveled, the three bags of white powder, I travel with really concerns, the TSA.” And so people started asking us, “Would you ever think about doing like a convenient product that I could take with me?” And it really wasn't on our radar, but there was a massive amount of interest. And we were seeing all of these super common side effects or difficulties of doing dietary shift. And it doesn't have to be a low-carb diet, even if somebody just goes from eating a very poor diet to say like a Mediterranean type diet, they experience a lot of the same symptoms. The fatigue and lethargy and everything because they're dropping their insulin levels, they're going to have some shifting around if they're electrolyte and sodium status and whatnot. We just saw all of these people, dietary change is so difficult anyway, because of social issues and psychological issues and whatnot. But if you feel like absolute garbage also, when you have no energy and you just hate your life, like you're really stacking the deck unfavorably for people. We realize that if we could help people bridge that gap when they're initiating dietary change, or if they've been in the scene a long time, but they're trying to exercise at a high level and whatnot, but they really need more electrolytes, in particular sodium.

The sodium piece is really something that's very different most electrolytes lead with potassium, and we do see potassium as being very important. But what we really drive people towards is eating a minimally processed whole food diet. Generally, they get most of the potassium they need in that scenario, but they get virtually none of the sodium. So that's why LMNT is so sodium heavy relative to the other constituents.

I will shut up here in a minute, but when we started putting this together, we weren't sure at all if this idea around LMNT would go. The first several flavors we put out, like the citrus salt, like the raw unflavored, and the lemon habanero. They were all formulated as drink mix bases also. If we failed as an electrolyte company, we were going to pivot and become like a drink mixer company. Fortunately, it's gone well on both directions with that. We didn't just sit down with this idea that we were going to spin up an electrolyte company and it was really recognizing my own personal need, which Tyler and Luis had recognized this need in the folks that they'd been working with for years. When we had this premium offering where we gave this “mix it yourself, home brew thing away" and we still do that.

When people are, “Well, I don't know, if I want to spend the money on this.” We're like, “Great. Just download the free guide, make sure you get your electrolytes on point, eat some pickles, eat some olives, just make sure you get enough sodium and everything's going to be good.” That's the genesis story, and it's been really cool, because we didn't need to spin up any type of like magical stories, like “Our salt is a secret salt from Pakistan, and there's only one source of it. And it's got this amazing mineral mix.” We didn't have to do any goofy, marketing stuff like that. It's like, “No, you probably need more sodium, and here's a million different ways that you could get it, but LMNT tastes really good and it's super convenient. So, we'll send you a free one, if you want to check it out.” Like any good drug dealer, “First one's free,” and then people get [laughs] and then just kind of off to the races from there.

Melanie Avalon: Oh, my goodness, that is so incredible.

Robb Wolf: That was a lot. Sorry, that was a lot.

Melanie Avalon: No, that was amazing. And you touched on so many things. I have so many questions. Historically, as hunter gatherers, when we were hunting and gathering, no processed foods, nothing from today, what was the average sodium intake?

Robb Wolf: That's a great question. One part to this story is that the way that meat is processed in the western world, animals are butchered and they're bled as part of the process. If you look at the sodium content of most mammals while they're alive, and this is spread throughout their whole body, like the teeth, the hair, the nails, the whole thing, but they contain about four, four and a half grams of sodium per kilogram of weight on average of the animal.

When you look at the sodium content of just meat, it's about a gram and a half to two grams of sodium. And this is because when the animals are bled, and it's interesting, a lot of cultures, like I lived in Southeast Asia for a while, Central America for a while. And people will make things like blood pudding and blood cheese where they collect the blood when the animals are butchered and they eat that stuff. And the highest sodium concentrations in a mammal is in the extracellular fluid. When an animal dies, the potassium, which is in higher concentrations inside the cell, tend to leak out and the sodium which is in higher concentrations outside the cell tend to leak in and they equilibrate. That's one place that hunter gatherers likely obtained a significantly larger amount of sodium in their diet.

The other part of this is that when we look at historical kind of analysis of the way that hunter gatherers lived, and also contemporarily living hunter gatherers, they don't drink massive amounts of fluids. I think that that's actually one of the kind of wacky things, like you sound like a crazy person to say, maybe we would be better off not drinking eight ounce glasses of water per day. But just recently, there were some pretty high-level folks that have been walking that notion back because what they're finding is that people end up in this state called hyponatremia, where their sodium levels are too low, relative to the amount of water that they're consuming. Folks may be familiar with things like sorority or different, like college hazing, when people are joining a fraternity or sorority, people in military, bootcamps, marathoners, triathletes, but if folks over consume water, they can dilute their sodium to such a degree that they can become sick, possibly hospitalized or even die.

Some of the problem that we experienced today is just, like, I love drinking a cup of coffee in the morning, but a cup isn't actually like six or eight ounces, like a cup is supposed to be its whatever container I can fill full with fluid and that is enough to start diluting your sodium levels, and then you start feeling kind of foggy headed and fatigued and whatnot. So, I think in the ancestral environment, both animals and humans are very, very good at finding things like salt licks, they tended to gravitate towards more salt rich foods. And then also they weren't consuming massive amounts of beverages throughout the day, which is ironic that we're plugging that gap with a beverage, but I think that is a way that we can do some of the more socially accepted or habit-based things of like having a drink to sip on throughout the day and whatnot, but we just make sure that there is actually some electrolytes in there and then we don't end up with the same problems.

Melanie Avalon: I recently did two different episodes all just on water. It was because we were talking before this, I've been researching deuterium depletion. Something I learned in those episodes was that a large portion of our water is created internally, we don't drink it. And that really blew my mind. Like that was a huge, huge reframe for me. With everything that you just said with the hunter gatherers, do you think that the amount of sodium they were consuming was similar to what we consume today? Or, if you're eating processed foods, do you think that's more than what they would have been consuming?

Robb Wolf: It would probably be significantly more than what any hunter gatherer was consuming. Sodium is the only kind of micronutrient that we have a taste for. Potassium chloride has a flavor and it tastes awful. Magnesium citrate has a flavor and it kind of tastes awful, but we have five sweet, salty, sour, umami, one of them is salt. Sodium is generally comparatively rare and hard to find in nature. And so it is interesting that most organisms have a taste and a drive for salt. Also, salt containing substances usually have some other nutrients that go with them and whatnot. But usually, when we look at the reconstructed diets of hunter gatherers, it was definitely not that five grams of sodium per day level that we've been recommending within say, like this kind of low-carb world, but it also looks like that doesn't make as big a point, so long as we get adequate potassium, and the other kind of profile of minerals is pretty good.

Melanie Avalon: Do individual electrolytes affect individual processes, or is it more about the overall balance of all of them on a granular level? What do electrolytes actually do? I know you mentioned like the potassium pump and things like that, but are they a nutrient? Or are they a signaling molecule? What are they literally doing?

Robb Wolf: I guess, both in some ways. I'm just going to focus on the metal ions in this. All of the electrolytes that we would consider would be sodium, potassium, magnesium, calcium, chloride, bicarbonate and maybe phosphorus, phosphate, but I'm not really going to look at the anions, the chloride and all that type of stuff, really going to focus on the metal ions. Calcium is a critical piece of muscle contraction, it plays a role in the actin-myosin crosslinking, and when those actin-myosin heads interact and kind of do that sliding filament thing when we contract muscles, calcium is critical in the clotting cascade. If we get a cut or a thrombotic event, calcium is critical in that process. Magnesium is critical in ATP production, it helps to orient the structure of ATP in such a way that the enzymes properly work in both building and degrading ATP. Those are important electrolytes, but they play very, in my mind secondary roles relative to sodium and potassium.

Sodium and potassium are really the energy currency of life. If people remember, college, high school biology, TCA cycle, Krebs cycle, the electron transport chain, all that--, that type of stuff, all of that is being driven by sodium potassium pumps. Our body will concentrate sodium in higher amounts outside the cell, potassium in higher amounts inside the cell and that gradient helps to then drive the electron transport gradient, the hydrogen ion gradient, which occurs in the mitochondria. So, the sodium potassium pump really is the big, big deal in this story. All these things are important. Magnesium is important, calcium is important.

Modern folks who eat a processed diet tend to overconsume sodium relative to these other constituents, and that's part of why sodium has had a bad rap and we can dig into that a little bit later. But it's worth noting though that if we have adequate sodium, in general people do well sorting everything else out. If the individual is a diabetic, hypertensive, they have high blood pressure, then we need to do some things, like just loading them with more sodium is not really going to help them all that much. But interestingly, allowing them to continue eating a poor diet and restricting their sodium also doesn't really help them all that much, ironically, we need to really modify their diet and lifestyle in a way that improves insulin sensitivity. And they go through some of that natriuresis of fasting and get to a normal spot with their blood pressure and their electrolyte status. But I would make the case that sodium is really the linchpin in this whole story, because if we get a little bit too much sodium, within about 15 or 20 minutes, our kidneys have filtered it and sorted that out. But if we are deficient in sodium, it's virtually impossible for the kidneys to get out ahead of that. And they will begin to shed potassium and magnesium, then it will stimulate hormonal signaling, where we pull sodium out of the bone. But when we pull the sodium out of the bone to buffer our extracellular fluids, we also pull calcium out of the bone. This is thought to be one of the drivers of osteoporosis, osteopenia, is low sodium intake, which then drives the tendency to remove both sodium and calcium out of the bone. It's a really dynamic process, and it's maybe self-serving because we put together LMNT to be very sodium forward, but we didn't do that. It's funny folks on the interwebs will say, “Oh, I like the product, but you really got the formulation wrong.” I'm like, “Well, we really understand the science better than everybody else in the scene.”

It's worth mentioning, just throwing it out there. We had a friend of ours go to Florida State University where Gatorade was developed ages ago. And if they have like a Gatorade Hall of Fame, and they have some of the original packages of Gatorade, and used to. There was a time when Gatorade provided a gram of sodium per serving. And then over the course of time that sodium has gotten dialed down and the sugar has gotten dialed up, because of this misunderstanding about the importance of sodium and really the hazards of adding sugar to our system.

Melanie Avalon: I sound super professional using Wikipedia, but one of the sentences on Wikipedia talks about the importance of sugar in electrolyte drinks for properly supporting sodium uptake, is that true?

Robb Wolf: It's true in certain circumstances. This comes from something called oral rehydration therapy. What they found, people in developing countries, if they get dysentery or some of these really terrible gut-borne pathogens, they can get diarrhea to such a degree that they can die quite easily from dehydration and from electrolyte imbalance. If somebody's throwing up a lot, they can die from alkalosis because they actually lose a bunch of stomach acid. So, those things are really important. In that oral rehydration therapy scenario, sugar does facilitate the uptake of sodium. But what's missed in that story is that there are lots of other co-transporters that also allow the uptake of sodium. Amino acids facilitate the uptake of sodium. Butyrate or beta-hydroxybutyrate. So, butyrate, if you're eating a high fiber diet, you're going to make short chain fats from that, and that facilitates the uptake of sodium, you're on a ketogenic diet. And this is one of the reasons why I know years ago, there were folks that were really concerned about the lack of fiber and that we would kill the mucus layer in the gut because we weren't feeding it. But what we find is, if we hit a level, a decent level of ketosis, the beta-hydroxybutyrate diffuses into the gut, and actually feeds the gut microbiota and some of the intestinal lining cells, that also facilitates the uptake. This is something that gets missed a ton in this.

Under fasting conditions, like medically supervised fasts, the one thing that folks are given to help them navigate this whole process is an electrolyte beverage that is heavy in sodium, but these folks are consuming nothing. And so how did they absorb this? And the body has another backup mechanism. One, a person in fasting would in theory be in a state of ketosis so that beta-hydroxybutyrate could be facilitating the uptake of the sodium, but also, we can bring minerals into the body via active transport. It costs us a little bit of energy, but we can absolutely do that. It proved that under life or death circumstances, putting a little bit of glucose in the mix can definitely enhance the uptake of electrolytes, but it's portrayed as if it's impossible to uptake electrolytes unless you have sugar with it, and that is absolutely patently false.

What we've done with our folks that we work with, it also begs the question, okay, if you're going to put sugar in there, how much like? Are you a 6’4” male or you're 5’2” female? Are you super active? There're all these different considerations there. What we do is just educate people about if you are working out at a very high motor output and you feel like you would benefit from some additional glucose, then here's how we would dose that alongside your electrolytes. But even in that case, I recommend that people get something like the diabetic glucose tabs because I like to handle those as completely separate entities. You've got the electrolyte piece and then you've got the carbohydrate or the glucose piece.

When I go to jujitsu, if it's all a bunch of old broken-down has-beens like me, I will just sip on some electrolytes while I'm doing my drilling and open mat, and it's not really that big of a deal. If it's a bunch of 22-year-old division two wrestlers that are now doing jujitsu, then I'll take 15-20 grams of glucose, because I would like that extra little pop while I'm training. So, again, I know I'm bouncing all over the place with this stuff, but the oral rehydration therapy is a real thing. There're absolutely super important applications for it. And it is completely false that that is the one and only way that one can bring sodium or electrolytes into their system.

Melanie Avalon: I'm getting hit with memories. I remember when I first went on a low-carb diet, and I was super intense about it and very legalistic in my approach, and I had a blood test and I fainted, which was really awful. But I remember I woke up and they were trying to give me some electrolyte sweetened thing. And I was like, “I can't have sugar.” [laughs] So, I refused it. Good times. But you touched on so many things. You're talking about how if the body needs sodium, if it can't get sodium, it's forced to excrete all of these other really important electrolytes. I can't really think of any other nutrient, where if you don't get enough of it, your body gets rid of other nutrients to balance. Is that the situation that's happening?

Robb Wolf: Yeah. It's a little bit getting inadequate dietary protein. If somebody is under eating protein. And there are a lot of people both in the vegan world and in the really extreme keto world that are terrified of protein. They're terrified of mTOR and growth factors, and they're going to get cancer and all this stuff. What ends up happening, these people lose lean body mass, they lose bone density, because a significant proportion of your bones are actually made of muscle, and then organs like your heart and your liver and your brain end up shrinking because your body is catabolizing the protein in your person.

Now some autophagy and some cellular turnover is beneficial for sure. Before COVID waylaid everybody, I had a talk that I was going to do called Longevity: Are we trying too hard? I'm really on the very conservative and skeptical side of the fasting camp. I think people do too much of it. I think they go way overboard. They should be-- instead of asking, “Should I do another 72-hour fast this month?” I would ask them have you done four days of strength training every week for the last six months? I think that there's a lot more upside and benefit to be had there. But we do store a lot of different nutrients, protein, electrolytes both in the bone and in the soft tissue. When we are depleted in that, if we're under eating those things, then we will strip those out of the body.

Melanie Avalon: You're really one of the only people that I've personally heard talk about with over fasting things like stem cell depletion. I haven't really heard anybody else say that. And I've heard you say it multiple times on different podcasts and I've thought about a lot. I recently interviewed Valter Longo and I asked him. I was like, “Is that a possibility?” And he was like, “Yeah.” I was like, “Okay.” I don't know, something I think a lot of people aren't really talking about. We're all about using the stem cells and upgrading the stem cells, but there might be a point where that could be too much.

Robb Wolf: What people forget is we only have so many stem cells. This is a whole potentially interesting thing. So, both of our girls were homebirths, and there's this really potent desire to get the placenta out and disengage it as quickly as possible, but that placenta will continue pumping stem cells into the baby for quite a long time. And that stem cell pool is everything that you're going to have for your whole life. And all these folks that are saying, “I'm going to live to 150,” and everything. Okay, well, you maybe based off of how many stem cells you have. But over the past 30, 40 years, the tendency has been, the baby comes out, they clamp the placenta immediately because there's his super misguided notion that the placenta is going to overfill the baby with fluids and there's going to be some sort of like hemodynamic catastrophe because evolution is that dumb. This is one of these things that just makes me absolutely crazy.

We have this pool of stem cells that need to last our whole life. And then we have cells that go through growth phases. And then different elements of the senescence phase that senescence can head into autoimmunity, into proinflammatory state and also into cancer. So, you don't want an overabundance of those, but something that folks miss is that exercise causes a conversion of senescent cells into either apoptosis getting rid of them, or back into a pre-senescent state. So, it kind of presses a reset button on that. But all of our cells have a certain number of replications. It's called the Hayflick limit. And it may be a little bit different in a full living organism than it is in a tissue culture, but this guy, Hayflick, noticed that after cells had divided about 50 times, they were done. Their telomeres were gone and they went through a very rapid senescence process, and they died.

One of the hallmarks of when people get pretty old, and then everything just fails all at once, is that they have depleted their stem cell pools. I did my first article on fasting in 2005. And then by 2006, I deeply regretted releasing it because it went out to mainly a group of CrossFitters, who were intermittent fasting 22 hours a day, eating five grams of carbs a month, doing six workouts a week, they would recover with hot yoga on the weekends and their hair was falling out. They had no libido, they had retrograde performance. And I'm like, “This is a stressor.” And if you're a type B, mellow desk jockey who does computer programming all day, doing a little bit of intermittent fasting is probably great. If you're a hard charging athlete who's doing three or four times the work output that a hunter gatherer would do, you don't need more stress. This is where I think folks in this biohacking community or whatever they lose sight that all of these things are a tool, and all of them have a dose response curve. And virtually everybody thinks that more is better.

It's funny, because I was really banging on Peter Attia for a long time. I'm like, “Dude, I think you're doing way too much of this stuff.” And more recently, he has really walked back the volume and the intensity that he's doing on his fasting. If we overlay also, I know we've gotten out in the weeds away from electrolytes. You look at what Bret Weinstein's work that he did back in 2004. So, all of this research looking at fasting and calorie restriction, and increased health span is mainly in lab animals. And it's mainly in lab animals that have been bred to--, what bred is found, particularly in the rodents, not so much the same application to the primates. But in these mice and rats, they've been bred in a way that they have exceptionally long telomeres. And has been dangerous for drug discovery, because it makes these animals super human, if you want to put that with regards to toxicity. They can deal with massively toxic environments, because they've got a huge amount of telomeres and stem cells that they can deal with things in an acute fashion. But these animals also suffer from massive amounts of cardiovascular disease and cancer later in life because of the evolutionary trade off with these elongated telomeres.

With the little bit of study that has been done in looking at animals fed a species appropriate diet, they get absolutely no benefit from calorie restriction. You only see calorie restriction when animals are fed a crappy lab child diet, which is like the penultimate definition of processed food. They're feeding these monkeys and mice, a chow that is basically processed grains with vegetable oils and sugar, because the researchers want to know exactly what they're eating, which is laudable on the one hand, but is dumb on the other because there's not many things that are uncontroversial out in the world. But the notion that highly processed foods are really easy to overeat and can be problematic for health, is one of the few things that won't start a fistfight, the interwebs. The case that I've made, that other people have made is that all of the fasting research that we've seen, all of the calorie restriction research that we've seen, maybe doing nothing other than illustrating that eating less of crap food is better than more of crap food, and that may be the alpha, the omega, the whole thing on it. And then we overlay that with this idea that overly aggressive fasting moves senescent cells through the life cycle more rapidly, which then brings up the stem cells, that sounds like a good idea. But what people don't realize is that we have a whole spectrum of cells that need to function at any given moment.

Some of our immune response to cancer involve cells that are partly through the senescent cycle. You don't activate mTOR complex one without cells that are in a mode of being partially down that that senescence route. And so, then we don't develop the natural immunity against cancer or the normal apoptotic processes. So, then you increase the likelihood of cancer in many regards, if we are overly aggressive on that stem cell depletion and just trying to expunge ourselves of every single senescent or quasi senescent cell. I'm in this mode where I think get sun on your skin, drink some coffee, lift some weights three or four days a week, do cognitively engaging activity, and sure, maybe once a quarter, once a month, do a one-day, two-day fast, great, but I am really, really suspicious of any type of additional benefit or upside. And in particular, when I see folks that just look frail and haggard, if they were driving on an icy road and their car went off the road, and they would be incapable of saving their own life, because they're fasting themselves so hard that they are literally a non-resilient organism, then seems ridiculous to me. And I'm totally in the minority on that. [laughs]

Melanie Avalon: I think it's really, really valid to think about. I actually just learned the other day that stem cells generate their energy through glycolysis. Do you think that has any implications for people on long term ketogenic diets?

Robb Wolf: It could, like red blood cells are exclusively glycolytic in most mammals. This is where I think as we've motored along, we have generally found that adequate protein with some degree of carbohydrate restriction seems to be really good, like the Bernstein Diabetes Solution for type 1 diabetes works miracles for people. But what they're doing is they're consuming enough protein, so that the liver can make adequate glucose via gluconeogenesis, and release that, but it releases it in a very steady time index fashion. It's very, very different than consuming any type of a dense carbohydrate source. We just seem to see fewer of the really deleterious side effects of people trying to be in this mega deep ketosis where they have unmeasurable insulin levels and whatnot.

Protein does release some insulin. If you're insulin resistant, maybe we want to find a way to reduce calorie load and carbohydrate load, so that we can restore good insulin sensitivity, but being afraid of protein because of the potential of gluconeogenesis and insulin release, I think, ends up being very counterproductive in long run. Wouldn't it be a bastard if we're killing some of our stem cells, because we're starving them of adequate glucose. And then when we get to be 80 years old, and we really wished we had those to help repair like an aortic arch weakness in our cardiovascular system or something, it's like, “Oh, sorry, we're all out of those.” We're all out of stem cells, that could create some more neurons in your brain or some more gut cells to help your gut lining heal or something like that.

This is where some people for a variety of medical reasons or if they're doing adjunctive cancer therapy, or whatnot, the really, really deep state of ketosis is something that I think they need and they want to pursue. But then for the vast majority of people, if just general body composition and health is the goal, I think that we make sure that we get adequate protein, we figure out if we run better on carbs or fat, and we find a way that we can spontaneously maintain our appropriate calorie intake. And that's really where the money is. Once people hit that point, I'm so suspicious of the benefits of much in the way of fasting beyond that. A lot of zone 2 cardio, a lot of strength training, a lot of novel cognitive activities, like learning to dance or a language or music. Like those things, we just have such great research and it also enriches your life today. That's another thing that I'm like, “Well, it benefits you now, and it will probably benefit you later.” Whereas this fasting stuff, I don't know, if somebody gets in a mode where they're like, “Well, I just feel really good. It's good for my productivity to skip breakfast, and then I do a lunch and a dinner.” That's great. I have no gripes around that but when people are compressing their feeding window to one hour a day and they're trying to eat 3000 calories in a single meal, and they've got gut issues from that, and their sleep is all disordered, then I think really driving the boat in a completely counterproductive position or direction, if the primary goal was supposed to be health.

Melanie Avalon: I'm just mentally preparing myself for all the [laughs] feedback and the questions I'm going to get from listeners. I've found that I've settled into, it is one meal a day, but it's like five hours probably of eating. I really benefit from the mental part of fasting during the day and the productivity and then just having a long, luxurious evening, seems to work with my sleep. It's really working for me, but I do wonder about that, that stem cell stuff.

Robb Wolf: That piece doesn't sound so crazy and over the top to me. Honestly, that does better emulate what would generally be accepted as an ancestral eating pattern, like hunter gatherers tended to hunt and gather throughout the day, then they all got back together in the late afternoon and evening, and they ate the bulk of what they hunted and gathered and it tended to extend out over a rather long period of time. So, that doesn't weird me out. Also, if your hair is not falling out, if you're not amenorrheic, if you're not cold, if your sleeps not disturbed, if your HRV score is good, it's like, “Okay, we're good.” But people will just go crazy, and they're like, “Well, I'm eating in five hours. What if I do it in three?” It's just this brinkmanship or they keep making it tighter and tighter and tighter, yeah.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, especially being the host of the Intermittent Fasting Podcast, I think the biggest disservice that has come out of the intermittent fasting movement is that people think-- they think it's like the be-all end-all solution, so that because you're fasting, what you eat no longer magically doesn't matter anymore, like kills me. And then the second thing, they think more fasting is always better. Like you just said, “If I can do five hours, I can do three hours. And if I can do one meal a day, I can fast for three days or four days.” And I just-- I don’t know I try to dismantle that as often as I can.

Robb Wolf: Again, I always have the caveat, if it seems to be working for people, if they look, feel and perform the way that they want, if it's working for their lifestyle, like if I had my ideal situation, I would do get up to a really big breakfast to jujitsu or some type of strength training around noon. And then I would do my final meal around two or three, and depending on the volume and the intensity of my activity, then I'd be done. But I have seven- and nine-year-old daughters and family time eating is important. I do big breakfast. My lunch is dependent on, if I did a lot of jujitsu that day, then it's another big lunch. If I was writing all day or podcasting, like this, then it's a very modest lunch. And then I just have a token dinner in the evening because we sit down and hang out and talk about the day and all that type of stuff.

Even though I'm saying all this stuff, I would ideally have a bit more of a constrained eating window, but just like my family obligations and social obligations, it makes it a little bit easier to do this, but I'm really, really flexible with it. If we get super busy-- The cool thing about fasting and ketosis and all this stuff, in my opinion, is it when people become metabolically flexible, if you're traveling one day, and all of your food options suck, you're like, “Fine, I just won't eat. I'll eat tomorrow.” I'm not going to get-- If you're gluten intolerant, then you're like, “I'm not going to eat at this sketchy restaurant, I'll just motor through and I'll get a ton of work done and I'll make it up on the backend.” That's awesome. I think the liberation that can be had from a metabolically flexible physiology, you can't make enough about that. But again, I just think that people go crazy on it and institute this kind of brinkmanship, where they're like, “Some was good, some more is got to be better, and that's when I start seeing people have some real problems.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, I think listeners are always pretty shocked to learn. The longest I fasted is 48 hours and I was like, “I'm not doing this again.” [laughs] I tend to eat every single day and I tend to do it in that longer window. I want to touch on one thing, I just didn't want to let it slip away. The rat thing you were talking about, the telomeres. Was that the thing-- I was listening to some interview. I feel like it was Peter Attia, it might have been Bret Weinstein, but whoever it was, was talking about how basically almost all the studies we've done on rats have been not incorrect, but misleading because of the rat species that was used.

Robb Wolf: Super incorrect, really incorrect, because if this hypothesis around their telomere length is accurate, and it's kind of been borne out because we use these animal models as a first line of assessing safety, and then things like Vioxx and stuff like that. Then we release it out to the populace, and what we find is in the short term, typically, people are okay, but when it goes on for two years, three years, five years, then we start seeing these potentially really negative downstream effects. And so Bret's whole case here is that the foundational toxicological screening that they do at the beginning of the drug discovery process is flawed, and then it flaws everything else as a consequence. And he released this back in 2003, I want to say, and it has been very unpopular within the drug industry circles. And this could be something as simple as they need to breed the animals in a different circumstance and/or they need to bring in some wild-type animals. There could be some ways to modify this so that we could do these things differently. But there's absolutely no will to do that, because it will absolutely limit the number of new drugs that are kind of brought online. But I have a little prickliness around that too, because virtually all of the new drugs that are brought online are addressing issues that are completely solvable via diet and lifestyle. This isn't addressing like a brand-new cancer therapeutic that that's going to save lots and lots of people with these rare types of cancers or anything. It's another anti-inflammatory drug, it's another hard drug, stuff like that.

Melanie Avalon: Didn't he try to tell people about this and was basically just ignored? If they accepted this, it would invalidate?

Robb Wolf: Yeah, I think he spoke before Congress about how important this was. It just went nowhere. As his podcast has grown, this thing has gotten a new life and has some more legs. But, yeah, it's a really interesting piece to this whole story for sure.

Melanie Avalon: Well, since we're talking about controversy and the findings and the data, coming back to electrolytes. When I was sitting down to research all of this, I was just thinking about how honestly the whole salt debate is something that I find so confusing, because on the one hand, there's all these people saying that low-sodium diets have beneficial effects, especially on things like blood pressure, but then there's a whole scrutiny of the data saying that it's misleading, or it's like U-shaped, or it's J-shaped, but then there's scrutiny of that and saying that, that is actually, there's a lot of debate out there. So, this controversy surrounding sodium, and particularly blood pressure, but other conditions as well, what are your thoughts?

Robb Wolf: It's interesting at a very superficial level. Years ago, when we talked about the amount of fat that was consumed, we were told that fat is this major enemy for cardiovascular disease and cancer and all these different things. And then some stuff popped up, like the French paradox and the Spanish paradox and, “Well, they eat more fat than Americans do, but they have fewer problems,” and it just kind of goes on and on.

One, I think that nutritional research is just really, it's difficult to do, it's usually not done that well. It's super complex, but some animal studies that looked at boluses of sodium being given again to animals raise blood pressure, so that was this thing and we're like, “Huh, okay.” And we know for sure that elevated blood pressure is a major cardiovascular risk factor. It is depending on where you are in this whole story of cardiovascular disease progression. There are some people that believe that the concentration of cholesterol, specifically lipoproteins, LDL lipoproteins, that is the driver of cardiovascular disease, other people make the case that that is a piece of it, but you need some sort of vascular damage to occur, like smoking or oxidized fats, or oxidized cholesterol or high blood pressure.

When our blood pressure is very high, we get what's called nonlaminar flow and movement of blood through our vascular system, laminar flow is very, very smooth and there's not bumps and kind of bubbles through it, but nonlaminar flow creates this turbulence that can damage the endothelium of our arteries. And then the cholesterol and the lipoproteins deposit there to begin the rebuilding process. It's actually part of the recovery process. But if that keeps happening, then you can end up with an atherogenic fatty streak. And I'm not entirely sure where I am on the-- is it all lipoproteins? Is it vascular endothelial damage? The more I look into this, the more I'm honestly confused, but when we look at the research on just what are people consuming with regards to sodium and cardiovascular disease rates are really simple one.

This is something that when the US Government started making low sodium recommendations, back in the late 70s, early 80s, some people pointed out that the Japanese consume three to five times more sodium than we do, but yet had a fraction to cardiovascular disease. So, it can't just be the sodium. And then they did pretty darn good studies, randomized controlled trials where they would get folks eating low-sodium diets and high-sodium diet. What's interesting in those scenarios is that the low-sodium diets decrease blood pressure a little bit, but it's really not that much. But what really seems to knock blood pressure down is finding a calorie load and a glycemic load that is low enough that people reverse insulin resistance. And then when they become insulin sensitive, they retain the proper amount of sodium instead of retaining too much. It is a complex topic.

The research on both high and low-sodium diets have been-- I want to say pretty clear, but to your point, you'll have people to get in and pick it apart. One of the things that I've been recommending that people do, is they just get like a $10, $15 home blood pressure cuff, and you just experiment a little bit. Let's say you're eating a low-carb diet, but you've had some lethargy and fatigue, and you're lightheaded going from seated to standing, which is classic symptoms of hyponatremia of low sodium. Let's see what your blood pressure is there. Now let's have you eat some olives and some salami and maybe use something like LMNT. And let's get your daily sodium intake spread out throughout the day from both food and supplement sources. Let's get it at least five grams per day and let's see what that does to your blood pressure. What we find is, people are not in mass developing hypertension. In some cases, people who had hypertension previously, when they consume the appropriate amount of sodium, their blood pressure actually goes down. Doesn't do this for everybody, but there is literature that suggests that inadequate sodium causes stress, and so we get an upregulation of both adrenaline, epinephrine and cortisol, because both of those are other hormones that cause retention of sodium. But those things are more stress hormone related and they have all these other deleterious effects.

It is a big gnarly knot, it reminds me of when my daughters refuse to brush their hair for a couple of days, and you've got this horrible, tangled knot. And I'm like, “I'm going to have to shave your head to [laughs] fix it this, this problem.” These nutrition problems strike me as being similarly messy and tangled. But we do have some pretty good research to lean on. Also, that kind of n=1 experimentation. If you're concerned one way or the other, then for a $10 or $15 investment and tracking your blood pressure, then you can figure out where you are in that story.

Melanie Avalon: The tendency to having hypertension or blood pressure issues, is that something that would most likely only manifest if you are eating a diet that would create that or if you are genetically predisposed to that, does it not so much matter? Could you be following on an appropriate diet and still have blood pressure issues?

Robb Wolf: Little bit of both. There's definitely a genetic component, there's definitely that epigenetic component of diet. But by and large, we tend to see hypertension track really closely with insulin resistance. When we fix that insulin resistance, then we tend to see that resolve. There's maybe 1% of the population or what we would call a sodium sensitive hyper responder, like they get a really massive transient increase in blood pressure when they eat a salty soup or something, they can feel it, they can feel their blood pressure has gone up. Not all of these people respond favorably to reduced glycemic load, but most of them do and what's interesting about those other folks, is it if they're eating a lower glycemic load diet, they're not experiencing any of the symptoms that you would need more sodium for anyway. They're not experiencing lethargy, fatigue, elevated heart rate. Their body is at a homeostatic level, that's fine for their situation.

Melanie Avalon: I was reading a review, it was effects of low-sodium diet versus high-sodium diet on blood pressure. It is called renin, aldosterone, catecholamines, cholesterol and triglyceride. It was 2017, and I looked at a ton of studies, but the biggest takeaway for me was just the massive difference between because you're talking about how they do studies on sodium restriction diets, and it doesn't have huge measurable effect on blood pressure. But it seemed to be that the biggest difference was whether or not you had hypertension originally. And if you did, then it has a much bigger effect. Although, I read the whole thing, and they didn't comment on this, but I thought this was so interesting because they were looking at it by race. It was Asian, white and black.

The Asians had the smallest change when they were normal. So, if they didn't have hypertension, they saw the smallest change in blood pressure when they went on a low-sodium diet. But on the flip side, they had the greatest change if they had hypertension. So, they were like on both ends of the spectrum. I was just wondering, like, maybe it has something to do with their metabolic health.

Robb Wolf: I don't know about metabolic health, but there's definitely some adaptations there. In general, Asian populations tend to show much lower rates of lung cancer in conjunction with smoking. This is where some of that more granular genetic stuff becomes important, and maybe doing a little bit of genetic testing to figure out, you do some of your snips and polymorphisms could be helpful.

But this is also where just doing a little bit of n=1 self-experimentation is super helpful. Modify this position going down the road, but right now if somebody is hypertensive, and they're like, “Do I need LMNT or electrolyte supplementation?” I would say, “No, but I would really like to see you modify diet and exercise in a way that we improve your insulin sensitivity and we can track that via a variety of ways. I really like the LPIR score or the lipoprotein insulin resistance score. And then let's see where you are then.” Have we resolved the hypertension at that point?

This gets out in the weeds a little bit, but in Chinese medicine, there's this recognition that the lungs and the kidneys are really tightly related and you're talking about, like renin, and angiotensin and whatnot. Some of these hormones are produced in the kidneys, but make their way to the lungs to be activated. This may be some of the benefit of mindfulness and breath work, is that it may modify the way that these blood pressure regulating hormones actually regulate our electrolyte status. There's not a ton of research on it, but mechanistically, it makes a lot of sense. But this is where understanding our genetic and epigenetic situation is really valuable. But it's also doesn't mean that our genes are our destiny, like we can get in and do some tinkering and modifying. But it also makes the case that, although someone like me, I really benefit from some aggressive sodium and electrolyte supplementation. Somebody else may not need that stuff, because just genetically their body is wired to hold on to sodium more effectively. And they may be-- even when eating a very healthy glycemic load for them, they may be at that borderline of the hypertensive state, and so they would really benefit from some zone 2 cardio, some sauna work, so that they're getting that low level cardiovascular effect and really tuning up their sweat glands for excreting sodium and whatnot. So, there's a lot of different ways to tackle that, so that people can customize it to meet their individual needs.

Melanie Avalon: I don't know why, I'm just so haunted by it. I guess it's because you would think with the Asian population, since they see the smallest change on reducing their sodium that if they are hypertensive, that they would still see-- out of the three races, out of black, Asian and white, that they would also see the smallest change even if they're hypertensive, but the fact that they see the greatest, why? Is it that they normally have something, like, you're talking about with the Asian diet, and like Japan and having a higher salt intake, they're genetically protected against it, but for some reason, if they have hypertension-- is there one thing that is off that would explain it? I don't know. I'm getting in the weeds now with it.

Robb Wolf: No, it's a really, really good question, and I don't even have a great speculative answer on that. Other than we do see some ethnic driven differences, in different disease potentialities and whatnot. Like within the medical risk assessment program that I've been a part of in Reno where we found 40 police and firefighters at high risk for type 2 diabetes, and we use this LPIR scores, some of our advanced testing, we modified their diet and lifestyle as best we could, like lowest carb paleo type diet. Got their sleep as dialed in as was possible given the demands of their work, and we had really dramatic changes in their metabolic health. The program ended up saving the city of Reno was estimated to be $22 million prorated over 10 years. It was like 33 to 1 return on investment. But within that population, if someone is African American, we modify the cut points more aggressively for what we want to see, both with glycemic control and with blood pressure, because within African Americans, the same some borderline high blood pressure, you see more kidney damage, and you see a higher likelihood of vascular events in African Americans than you do in Caucasians and Asians. This is all like super controversial stuff these days. You're talking about trying to save people's lives and now people on the interwebs have gone so crazy that you can barely even talk about this stuff. But you can have two people, different ethnic backgrounds, same height, same weight, same blood pressure, borderline high, and one of those people is at a higher cardiovascular disease risk and a higher kidney disease risk because of their genetic predispositions.

Now, it's somewhere in that evolutionary story, those folks that are at higher risk, for that, have an advantage somewhere. This is where biology is all about tradeoffs. If you're super-fast twitch, you may make a great basketball player or sprinter, but you're going to be a terrible marathoner or triathlete, and so it's not that there's anything wrong with any of these people. This is just the genetic bag of-- deck of cards that they were dealt, and we have to better understand what's going on there. But we purposely modify the cut points more aggressively, because if we don't, we know based off of MESA data, Women's Health Study, the Nurses’ Health Study and whatnot, that African Americans are at higher risk for different complications at metabolic cut points that are more benign in Caucasians or Asians.

Melanie Avalon: Speaking to that, just to paint a picture from this study with the sodium change. I'm using the word black, because that's what they call it in the study. White people who did not have hypertension, who went on low-sodium diets saw a reduction of 1.09 millimeters per mercury, is that the way you would phrase it?

Robb Wolf: Mm-hmm. You could just call it one point. Yeah.

Melanie Avalon: White people with hypertension was 5.51, but then black people who did not have hypertension was 4.02. So, almost the same as white people with hypertension. And then black people with hypertension was 6.64. And that's where the Asians were on two different sides. Without hypertension, it was 0.72, but then with hypertension, it was 7.75. So, the intuition surrounding all of this. You were talking about how there is an evolutionary advantage to things, even if they seem they, they might manifest as a health condition or a bad thing. But somewhere along the line, there was an evolutionary reason for it. When it comes to electrolyte intake and intuition, how intuitive are our bodies for getting adequate amounts of electrolytes. With LMNT, for example, should people just take a pack, and if it tastes super salty, does that mean something? How do people know how many electrolytes they need?

Robb Wolf: Sure. That's a really good question. Honestly, it's one of the most difficult things to answer. People say, “How much do I need?” And it's like, “I really don't know.” “Are you a large male, small female?” We spent two years living in Texas where on Christmas day, it was 90 degrees, and like 90% humidity, now we live in Montana. All of those things change the parameters a lot, even within very mainstream guidelines, the American Council of Sports Medicine, athletes that are training in hot humid environments, or at altitude, and at high work output, they put the need at least 7 to 10 grams of sodium per day. This is super mainstream orthodox medical circles and they recommend for an athlete that, we started having a conversation, at least 7 to 10 grams of sodium per day. We've done work with like professional hockey teams and some other folks that really track the electrolyte loss for these folks during a game or a session.

Some of these big guys, what we call super sweaters, the sweat just pours off of them and they tend to have a much saltier sweat. They will lose 10 grams of sodium in an hour, hour and a half game or practice. And if they don't replace that, they are a disaster, they don't recover, they don't sleep. There's just a massive spectrum on this stuff. And your question is really good. What's the intuitive or qualitative thing that we could use on this? One of the things to look at is, just being aware of the signs and symptoms of low electrolyte status. Hyponatremia, and lethargy, fatigue, brain fog are all early stage pieces. When we start getting cramping, you lay down at night and you go to stretch your toes out and your calf cramps, like you're really far down the track of low sodium and low electrolytes. You've gone really far on that. Cramping is an indication that we are really sodium and electrolyte deficient.

Some of these other things like lethargy, brain fog, high heart rate, when we lay down to go to bed, low HRV score, these are all very consistent with that. We have noticed this is very unscientific, there's absolutely no randomized control trials to support this. But what we've noticed is that if folks mix something like LMNT and they put it in, say, like 32 ounces of water, so not super concentrated, but it's not super dilute. What we find is that when people are in need of additional sodium, all that they taste is sweet. And then when they hit a point where they're topped off on sodium, they start tasting the salt. And they're like, “I don't know, that I really want anymore.” So, it takes a little bit of paying attention to some of those subjective symptoms, like the lethargy, brain fog, fatigue, cramping, and then paying very pretty close attention to how something like this taste.

Now all that said, we do also recommend that people get it as much of the sodium as they can from other dietary sources. Things like pickles and olives and salami and stuff like that are really, really good sources because you get a bunch of other nutrition. LMNT is fantastic, love it when people buy it, but I'm really not envisioning that people get their full sodium allotment from LMNT. I'm really hoping that they get the vast majority of it from their diet based around whole minimally processed foods that some of them also come with a decent whack of sodium.

Melanie Avalon: Just looking at what I eat. I eat a massive amount of seafood, oftentimes scallops. With the amount that I eat, it actually says that I get “RDA for sodium” because I eat so much of it. One other question I had though about the sodium and the intuition. Does the body reach different homeostatic baselines of sodium based on what you're eating? I tend to eat very simply, and that I have the certain types of foods that I like, and I go through times where I'm eating a lot of one type of food and then a lot of another, but the consistency is there's always high protein. I play with the macros, but sometimes I go through saltier phases, and with the actual food itself. I feel I will hit a baseline. Eating that amount of salt won't make me feel I ate a lot of salt. But then if I'm on a lower salt run, and I eat salty meal, I massively feel it. I'm sweating the next day and excreting water. Is there a timeline of adjustment where the body adjust to salt intakes?

Then a follow up question would be, would that make the argument that, not minimum effective dose but if the body does reach some sort of baseline? Is it better to be at a lower or a higher baseline? Or does it matter?

Robb Wolf: Hmm, man, those are great questions. Your questions are going to be 10 times better than my answer. The kidneys are really quite good. All things being equal and we're not suffering metabolic derangement and insulin resistance and whatnot. The kidneys are really good at sorting out our sodium intake. If we go a little too much, they will filter it out, excrete urine, and all is kind of good. Usually what you will notice with that, is possibly increased thirst. Ages ago in sports circles, the coaches would tell athletes and kids to suck on salt tablets, and then just sip on water per satiety. And this was actually a really shockingly smart recommendation because you had the sodium there that would stimulate the desire to drink water, but then you weren't diluting the sodium to such a degree that we ended up in a hyponatremic state. The body's pretty good at regulating that side of things.

And then that minimum effective dose story, I guess there's something to that, but it strikes me as a pretty dynamic process. I'll just use the example of living in Montana like. We are at 3000 feet elevation, so not real high, but certainly not sea level, but typically it's pretty dry here. But the past couple of days, we had some thunderstorms, the ground was absolutely saturated with water, and then the sun came out, and it was like 94% humidity and 85 degrees. It felt like Costa Rica or Texas or something like that. And I noticed that my baseline desire for electrolytes was much higher, like much, much higher because I was just sweating a lot. Hot weather is so infrequent in Montana, that we don't even have an air conditioner, like you just open your doors and windows in the morning, the house gets cool, you button it up, and then it carries you through the whole day. Whereas, it was hot outside, it was hot inside, I was sweaty and uncomfortable all day. And I noticed that my electrolyte intake was much higher than what it was otherwise, just like my desire for it.

Man, it's a good question, but I think that is just a really dynamic, changeable process, depending on what your situation is. Being on an airplane, you would make the case that you would probably want to hydrate crazy, because the air is super dry and dry air tends to, ironically, lead to dehydration, which is the loss of the water and we tend to see an uptick in sodium excretion. But what do you not want to do when you're on an airplane? Run back and forth to the bathroom, like 30 times through the flight. [laughs] Just the dynamics of life, I think are going to be huge drivers on that. I probably did a terrible job answering that, but I think it's just a very dynamic process.

Melanie Avalon: It's a very nebulous concept. It's probably like so many things I talk about, it really is just an individual. There's not one answer and like you said, it's dynamic and changing. Just to clarify, the level of using electrolytes for hydration, is that also on a spectrum? Do electrolytes support hydration up to a certain point? But then if you have too much, would it support dehydration?

Robb Wolf: A solution could be hypertonic, where it has more things dissolved in it than what is dissolved in our body. If you drink a hypertonic solution, you can get really bad gut ache and possibly even diarrhea from that, because it will actually pull fluid out of the body to dilute it in the intestines, and so that would be a problem. There's isotonic where it is the same amount of dissolved solutes in that water. And that's like the nice sweet spot, and when people put LMNT in about 30 to 32 ounces of water, it's about a hypotonic solution slightly on the hypotonic side. And then the hypotonic is where you-- and this is where people end up with Gatorade, and in most of the electrolyte options that are available, they have electrolyte in, but they are such small amounts relative to the fluid being consumed, that it really doesn't help you. You still ultimately end up in that hyponatremic state because although we don't want to overly lose body water, which would be dehydration, you also--, it's arguably much more dangerous to end up in a hyponatremic state that sodium potassium imbalance, then it is dehydration.

When you look at the medical literature, unless somebody is trapped in a mine cave-in or they get lost in the desert or something like that, nobody ever dies from dehydration, like humans will find a way to get some fluid in themselves, but people routinely will overconsume water. Again, like these hazing rituals with fraternities and sororities, military training, marathon, triathlon, where people will drink a set amount of water every two miles or whatever and it's absent electrolytes and they can end up in a hyponatremic state and be hospitalized or potentially even die.

Melanie Avalon: I'm so glad you touched on that, because I was actually wondering that--, and it's a really naive question, but I was wondering if like LMNT had to be dissolved in water? Or could you just add it to food for example?

Robb Wolf: The balance is important. But some people have been using-- it wouldn't in my mind be much different than using salt unlike a steak or some folks were putting the mango chili on watermelon slices. And it's like other world, it's so good. So, it can also just be a seasoning too.

Melanie Avalon: Okay. Are you thinking of making any non-drink seasonings?

Robb Wolf: We haven't really thought of that too much. We've just been spinning up recipes with the ones that we have and like, “Oh, yeah, you could use it with this or use it with that.” But we haven't really thought about like a seasoning line around that. No.