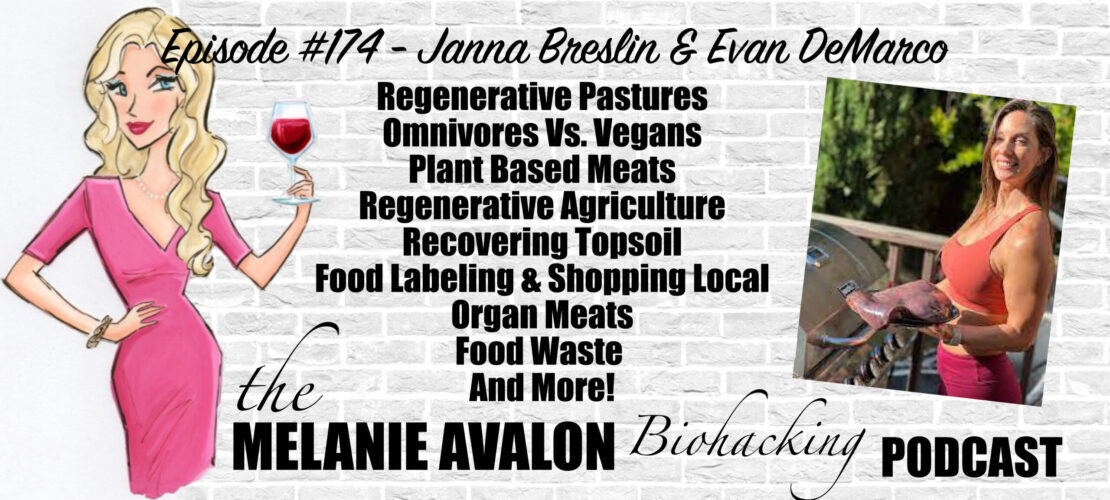

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #174 - Janna Breslin & Evan DeMarco

A growing number of people think cows are killing the earth and going meatless is the answer to saving the planet, and let’s be real, this couldn’t be further than the truth. The issue is that vegan advocates are louder than the regenerative agriculture advocates. Plus, most people are clueless when it comes to what regenerative agriculture even is and what benefits it brings to our planet.

Janna Breslin and Evan DeMarco want to change that.

Janna and Evan are the founders of Regenerative Pastures and are beyond passionate about using regenerative agriculture not only as a solution for climate change but also as the solution to the health epidemic in the world today.

LEARN MORE AT:

regenerativepastures.com

@regenerativepastures

@jannabreslin

@evan_demarco

SHOWNOTES

go to regenerativefarms.com to get 40% off your first box and ground beef for life with the coupon code MELANIEAVALON!

2:35 - IF Biohackers: Intermittent Fasting + Real Foods + Life: Join Melanie's Facebook Group For A Weekly Episode GIVEAWAY, And To Discuss And Learn About All Things Biohacking! All Conversations Welcome!

2:50 - Follow Melanie On Instagram To See The Latest Moments, Products, And #AllTheThings! @MelanieAvalon

3:35 - AVALONX BERBERINE: This Natural, Potent Anti-Inflammatory Plant Alkaloid Reduces Blood Sugar And Blood Lipids, Aids Weight Loss, Supports A Healthy Body Composition, Stimulates AMPK And Autophagy, Benefits Gut Bacteria And GI Health, And More! Stock Up During The Launch Special From 12/16/22-12/31/22!

AvalonX Supplements Are Free Of Toxic Fillers And Common Allergens (Including Wheat, Rice, Gluten, Dairy, Shellfish, Nuts, Soy, Eggs, And Yeast), Tested To Be Free Of Heavy Metals And Mold, And Triple Tested For Purity And Potency. Get On The Email List To Stay Up To Date With All The Special Offers And News About Melanie's New Supplements At avalonx.us/emaillist!

Text AVALONX To 877-861-8318 For A One Time 20% Off Code for AvalonX.us

7:30 - FOOD SENSE GUIDE: Get Melanie's App At Melanieavalon.com/foodsenseguide To Tackle Your Food Sensitivities! Food Sense Includes A Searchable Catalogue Of 300+ Foods, Revealing Their Gluten, FODMAP, Lectin, Histamine, Amine, Glutamate, Oxalate, Salicylate, Sulfite, And Thiol Status. Food Sense Also Includes Compound Overviews, Reactions To Look For, Lists Of Foods High And Low In Them, The Ability To Create Your Own Personal Lists, And More!

8:00 - BEAUTYCOUNTER: Non-Toxic Beauty Products Tested For Heavy Metals, Which Support Skin Health And Look Amazing! Shop At beautycounter.com/melanieavalon For Something Magical! For Exclusive Offers And Discounts, And More On The Science Of Skincare, Get On Melanie's Private Beautycounter Email List At melanieavalon.com/cleanbeauty Or Text BEAUTYCOUNTER To 877-861-8318! Find Your Perfect Beautycounter Products With Melanie's Quiz: melanieavalon.com/beautycounterquiz

Join Melanie's Facebook Group Clean Beauty And Safe Skincare With Melanie Avalon To Discuss And Learn About All The Things Clean Beauty, Beautycounter And Safe Skincare!

12:30 - Janna and evan's beginnings

16:45 - janna's cancer diagnosis

17:55 - are modern agricultural processes necessary?

20:45 - what is regenerative agriculture?

25:45 - do we have enough space to pasture enough animals?

28:15 - what is AUM based on?

30:50 - the state of our topsoil

32:30 - can we restore the topsoil with any technology?

34:00 - what about greenhouses or reintroducing nutrients to the soil?

35:15 - food waste

36:20 - FEALS: Feals Makes CBD Oil Which Satisfies ALL Of Melanie's Stringent Criteria - It's Premium, Full Spectrum, Organic, Tested, Pure CBD In MCT Oil! It's Delivered Directly To Your Doorstep. CBD Supports The Body's Natural Cannabinoid System, And Can Address An Array Of Issues, From Sleep To Stress To Chronic Pain, And More! Go To Feals.Com/Melanieavalon To Become A Member And Get 40% Off Your First 3 months, With Free Shipping!

39:00 - planning food systems on another planet

42:00 - the morality of eating living creatures

45:35 - the backlash on social media

48:15 - is it possible to get enough protein as a vegan?

50:50 - nutritional profile of feed lot animals vs grass fed

52:30 - omega-6 to omega-3 ratios in meat

57:10 - fish and toxins

58:35 - detoxing mercury

1:01:05 - cryotherapy and ice baths

1:01:04 - toxins in conventionally raised livestock

1:07:30 - methods to reducing stress of the animals

1:12:00 - do livestock have better lives then if they were wild?

1:15:25 - what happens during processing?

1:16:35 - the natural circle of life

1:19:30 - food labeling

1:22:45 - the role of large industry in agriculture

1:25:20 - shopping local

1:26:30 - agricultural subsidies

1:28:00 - BLISSY: Get Cooling, Comfortable, Sustainable Silk Pillowcases To Revolutionize Your Sleep, Skin, And Hair! Once You Get Silk Pillowcases, You Will Never Look Back! Get Blissy In Tons Of Colors, And Risk-Free For 60 Nights, At Blissy.Com/Melanieavalon, With The Code Melanieavalon For 30% Off!

1:31:30 - the inedible offal

1:33:15 - the carbon problem and greenhouse gases

1:37:30 - reversing climate change

1:39:30 - impossible meat

1:41:00 - Evan and Janna's Businesses

1:44:15 - the mental health and wellness of the ranchers

1:46:40 - what Evan and Janna's cows eat

1:47:15 - wagyu beef

1:48:45 - ground beef

1:50:15 - beef heart

1:50:30 - organ jerky

1:53:10 - oxtail

1:55:30 - why don't we crave organ meats?

Go To regenerativefarms.com To Get 40% Off Your First Box And Ground Beef For Life With The Coupon Code MELANIEAVALON!

TRANSCRIPT

Melanie Avalon: Hi friends, welcome back to the show, I am so incredibly excited about the conversation that I'm about to have. It is about a topic I am personally obsessed with, very passionate about and a topic that I've talked a lot about on this show, and a topic that I think is very debated and just very confusing and it's all sort of a few topics. So, that is the role of meat in our diet and our health versus an entirely plant-based diet, as well as the role of sustainable agriculture. What does that actually practically look like? What is sustainable agriculture? How does meat affect the environment? How does it affect our health? How does it affect the planet? So, many things and I will just say that, because I do a lot of interviews on this podcast and a lot of different perspectives and opinions on, and I personally myself even get really confused when it comes to all of this. I mean just even sitting down and looking at the scientific studies and data and points and everything it seems all sides can make all of their cases. I was super thrilled when two incredible human beings reached out to me. That is Janna Breslin and Evan DeMarco, they have a farm called Regenerative Pastures. And so, they have their own farm. And they also work with farmers to create a direct-to-consumer subscription-based regenerative process that we will talk all about in this show today. So, they reached out, I was obviously super down. And while I was just talking to him a little bit before this, and then just in the initial pitch that I got, they're very spirited, and have a lot of opinions. And so, I am just really, really looking forward to this conversation. So, Janna and Evan, thank you so much for being here.

Janna Breslin: Thanks, Melanie.

Evan DeMarco: Yeah, thanks, Melanie. Thanks for having us.

Melanie Avalon: To start things off, I've been wondering this ever since you guys reached out, I am dying to know your backstory. I mean because it takes a lot I think to do what you're doing, start a farm. Were you always into regenerative agriculture? When did that start? How did you guys meet? I just want to know.

Janna Breslin: I know there's a lot, going on. Yeah, Evan and I met a couple of years ago, we both been in the health and wellness space for many, many years. I've had social media following and have done many things with fitness magazines and bodybuilding shows and a lot of health and wellness categories. And for me, I actually had some health issues that really inspired me to really dive deep into how I can optimize my body. And it really started after I got a cancer diagnosis. And my body just seemed it was betraying me, failing me and I was like, "Okay, I'm committing everything, all of my time, all of my effort to find out what I can do to optimize my health. This comes down to nutrition, our movement, our mindset, our lifestyle, so many things that." Evan and I met, and we obviously had just a ton of synergy and it really has evolved. But no, neither of us really has any experience in the regenerative space or I mean, not experience but we did not grow up on ranches and farms. This is not something that it's in our backstory. This has been definitely a very inspiring journey that very much. We basically just found that it was so important for us to focus on our food and how we're interacting with our environment.

Evan DeMarco: Yeah and I think to elaborate on that Janna and I began Complete Human, which is a digital content platform and dietary supplement business about three years ago. And part of that was this recognition that we needed to continually optimize the human condition. A lot of people talk about biohacking, we say bio-optimized because I just don't the term hacking. It's never a good thing. But in that, we're always talking about supplements, we're always talking about working out, we're talking about mindset. But we've always, I think, as an industry really shied away from talking about how important our food is in this whole health and wellness journey. And so along the way in this digital content place, one of our friends called us up and he's like "Hey, would you guys like to do a documentary on regenerative agriculture?" And our first response is "What the hell is regenerative agriculture." So, he sends over this whole data dump of stuff and that was Allan Savory's TED Talk, really getting into the kiss-the-ground movement, looking at all of the different scientific research that has evolved in the space of regenerative agriculture. And after just geeking out on it for a week, we called them back and we said, "Hey, we don't want to just do a documentary on this, we actually want to get really involved." We recognize how powerful regenerative agriculture is in really changing the entire trajectory of the planet.

So, his response was, "Well, do you want to buy a USDA processing facility?" And we're like "Sure, why not?" And so, we did that in Cody, Wyoming and the joke is, we've wanted to kick him in the nuts every day since then because buying a processing plant is a labor of love. It's not economically viable and this is really one of the things that we're going to talk about in this podcast is how much we've marginalized the people in this country who produce our food. And that's from, the people who process our animals, the people who grow our vegetables and our fruits. And in this, we've really started to understand the whole model, the entire value chain of our food supply, and how broken it is. And that led us of course to recognize that by optimizing that by owning the processing facility by owning the ranches, by working directly with the farmers and cutting out all of these middlemen, the brokers, the auction houses, the people in New York who are trading cows as a commodity, who've probably never even seen a live cow, we can now start to really have a significant impact in how we eat as a country, how we take care of the people who manufacture our food, and then how we start to look at the food the way that we once did, which is with a little more reverence than we do. And I think, again, as this podcast unfolds, one of the things that we're going to really hammer home is "how disconnected we are from our food supply, and how through the process of regenerative agriculture, we can develop that connection, we can reconnect with our food supply and understand how important it is to the health of ourselves as individuals and the health of the planet."

Melanie Avalon: Well, first of all, Janna, how did everything go with your cancer diagnosis?

Janna Breslin: It went good, I mean, literally, ever since I just dove into how I can help myself in all ways, and I'm sure you understand this as well. But it's not just the nutrition and the workouts. It's our mindset, it's our lifestyle, it's our relationships and our relationships with ourselves. I think that especially when we're bombarded with our toxic environment, there are a lot of things that we need to do to help heal ourselves. And I think when you support the body as a whole, everything starts working a lot better. Ever since then, things have been much better for me. Thank you for asking.

Melanie Avalon: Awesome, that's amazing. It's so interesting. Do you guys know Farmer Lee Jones?

Evan DeMarco: Yes, not personally, but.

Melanie Avalon: You guys should meet him because he's the most passionate, inspiring person, he's the person that you talk to him and you're just smiling. But I was just thinking about that interview because when he came on, I don't remember what he said at the beginning. But the first question I asked him was what you were saying was sparking in my head. I'm going to ask it again. It's a societal question because you're talking all about the role of all of these people and processes that are involved in our food system, and how we don't see any of that. This is like a big question, America and progress and society. Because there's this movement now with what you guys are doing a lot of similar farms to sort of return us more to a state that's different than we are today with conventional agriculture and how things are done. But could it have happened any other way? So what we're trying to get to today? Could that always have been the way it was? Or do you think we had to go through the system we went through to progress as society?

Evan DeMarco: Ooh, that's a great question. let's take a step back in time and we recognize that harmony or this harmonious relationship that humans always had with the planet was how we evolved. And it wasn't really until we can say the invention of the plough was the beginning of that, shall we say downward spiral, but really the Industrial Revolution. We sent people off to the Midwest to these farms to live in these smaller communities, to grow their own food, to work in harmony with the land. And it wasn't until the Industrial Revolution, where we started to pull people back to the cities. And we recognize that in these major metropolitan areas, in New York or Philadelphia, Chicago that we had to feed massive amounts of people. The only way to do that was through this massive industrial, agricultural complex and in that the downward spiral really escalated.

The question is, could we have gotten to this place if it wasn't through the tumultuous last 150 to 200 years of really this industrial growth? I think the answer is probably no. I think we had to understand our impact in the world as a technologically evolving society for us to recognize that we have to almost go back to those preindustrial practices, to reengage in that harmonious relationship with the environment. However and this is something that I think I get very passionate about is, we oftentimes think that technology is the savior, when in fact I think it's going to be the downfall. We can absolutely value technology and certain types of technology in our quest to create a better world. But if we think it's going to save us, and that's in the form of what's just lab-grown meat or any of the other things that really are trying to take the place of that holistic relationship with the world. We're going to screw it all up even worse and then we're just basically going to run ourselves into extinction.

Melanie Avalon: You mentioned this, I mentioned this, when people hear regenerative agriculture it's so funny because I think now I'm so familiar with the term, I say it all the time, I say it casually, and I assume that people know what it is. But I was talking to some friends yesterday telling them that I was having this interview today. And they were what's regenerative agriculture? And I was "Oh," so can we put in place some definitions about what this even look like?

Evan DeMarco: Great question and that is the unfortunate part about regenerative agriculture in this movement is there's not this singular definition of what it is, you think of organic and that has a very concrete if not government oversight type of definition. Regenerative in our opinion, when I'll say ours, but Janna please feel free to jump in here is this return to how the world is supposed to work, how nature is supposed to work, and that is the synergistic blend of animal, man, and plant in harmony with the environment. And the best way to look at regenerative is, from the basis of a ruminant animal, cows, bison, whatever are packed together in these tight formations as this defense mechanism against predators. And they eat grass, they pee, they poop, they do their thing, and then they move quickly throughout the land so as to not deplete the land of that entire supply of grass, but just to move on as nomadic animals did. And what happens when they do that is that excrement that all of that stuff, their hoof tracks, their hoof movements in the ground actually creates a whole ecosystem, better soil, better water infiltration, the roots of that grass actually reach deeper which then sequesters more carbon and then that grass grows, and then the animals come back at a certain point, and then you have this whole cycle of life. But what has happened since the industrial revolution is we take these cows and we put them in feedlots, 10s of 1000s of cows, and they completely devastate the land. So that cow or that small group of cows pooping and peeing in small amounts and then moving on is very healthy. Lots of cows pooping and peeing in the same spot year after year is completely toxic. So, the regenerative movement really is this recognition that if we live in harmony with the land, we do exactly what animals and humans and plants did 1000 years ago, 2000 years ago, that's the model. And if we stick with where we're at right now, which is putting a bunch of animals in a pen and hoping that the world is going to get better, well, that's just fool-hearted.

Melanie Avalon: When you say moving like, "How far were they moving? How much terrain were they covering?"

Evan DeMarco: Enough that base, think of it this way if you had a giant herd of bison and we use bison as this regenerative icon. They would go maybe a mile a day, not a lot, it's not they're traversing hundreds of miles a day, it's just enough that they instinctually knew that if they stayed in one spot they were going to desecrate their food supply. They also recognize that by moving, the momentum of the herd was a natural defense against predators. So, just that continual movement of a herd is what did that and it could be a mile, it could be five miles, but it was really just that consistent understanding or that natural understanding of that animal or that herd of animals to move through the land, not completely destroy the food supply, but just keep chasing the grass.

Janna Breslin: The ground needs to rest too, the grass needs that time to replenish and grow and have stronger roots. So, if these animals are confined in one area, they're eating it literally to the bottom and it is destroying the grass. The fact that they can move it gives the grass and the plants more time to grow and nurture the soil better and that just helps our environment. Actually, moving these animals and not keeping them confined is probably one of the biggest parts to regenerative and helping our environment.

Evan DeMarco: It is and now that we've started to understand how these animals lived in harmony with the land a 1000 years ago or even 200 years ago, we can in a technological way or at least a cattle way, start to reimplement some of those processes. It's called "Holistic Management" is those cows, those bison, whatever, they're just moved every 18 hours. So, rather than using wolves, or Native Americans with spears and bows, we actually just use cowboys to simulate that natural predator defense, we move them through, and then that land starts to regenerate. And what we see from that is, again, soil health is everything. And as goes the soil, so does our planet. And we're starting to see that in the Midwest, we're starting to see that in these areas that are monocropped with high levels of pesticides and herbicides and fungicides, the soil is dead, and we think that tilling the soil is actually helping but it's making it even worse. Whereas if we utilize the excrement of these animals, we utilize their natural eating methods where they eat the grass down a little bit, and then the roots system goes deeper and deeper and deeper, making that root system stronger, sequestering more carbon, which then feeds the grass to grow, we have what basically the planet is designed to do, and that's to regenerate itself.

Melanie Avalon: On the land piece, one of the things that the plant-based people will often say is that there's not enough land or that animals require too much land to be sustainable. So, what is the role of actual land?

Evan DeMarco: I'm not sure how opinionated I can be with my four-letter words.

Melanie Avalon: Anything goes? [laughs]

Evan DeMarco: I think it's apropos for the conversation, but it's total bullshit. Now, one of the reasons for that is actually the way that the government has stipulated more through policy and policy that has been influenced by, shall we say, a contingent of the population that disagrees with eating meat that there's only a certain number of animals that can be on the land at a time. And that's AUM's. And that's a designation that only a certain number can be there. And what we found is that when we step outside of those natural or not natural when we step outside of those kind of government-mandated policies, and add more animals to the land, we have better regeneration. The truth is that the more animals on the land, the better off we're going to be. And let's look back to the bison days before the settlers came in and really destroyed the bison and probably what could be considered one of the most horrific things that humanity has ever done, just think of the thriving grasslands in the Midwest. And that was all a result of these millions and millions of bison who just called that home. And now when we say that on 1500 acres, you can have 40 pairs of cows. We wonder why we're screwing with things like man's foolishness and ego to think that we have the answers to what mother nature did so well for so many eons long before we showed up is just the ultimate testament to how sometimes batshit crazy we can be and more importantly, when we allow a policy that is dictated by a certain contingent of the population, predominantly vegans, to dictate that we don't have any real clear science outside of what we know independent of the government organizations to say that this actually has a positive impact. The research studies that say "When we increase herd density when we increase AUMs, we actually see better carbon sequestration, we see reversals of desertification, we see better water infiltration, better microbial growth in the soil." All of that is the essential component for us to fix a lot of the climate problems that we as a species have created.

Melanie Avalon: And this is where all the confusion comes in. Because everything that you just said is the antithesis of what another side might say. I think it's just really confusing to people. So that AUM number, what was that based on? How did the government come up with that?

Evan DeMarco: I don't know, darts at a dartboard, who knows?

Melanie Avalon: I guess what is the purpose of it?

Evan DeMarco: If the purpose was actually to mitigate the number of animals on the land because there was this propensity to put them into confined areas. And in those confined areas, we saw the degradation of the land, based off of what we now know happens and again if they're all pooping and peeing in one acre of land and it destroys the land, well, then yeah, we have a viable argument to say, well, these are detrimental to the environment. But when we remove those fences and we allow them to just roam freely, well then all of a sudden we start to see this regeneration. The AUMs have really just been this government oversight that's not based on anything hardcore science or data driven. It's more just based off of theoretical practices without really comparing and contrasting to control groups and saying, "Well, what happens here if we increase the number of animals versus over here where we decrease it, and when we see that in practicality, in practice, in the wild, we know that the greater the herd density, the better the environment, the better the soil, the better the grass. And so now, I think the Bureau of Land Management is starting to come around to some of these practices, we're starting to see that when we do these practices, when we increase the number of animals, and we treat them they were treated 10,000 years ago, we have a much better environment than the environment that we are trying to manufacture through policy.

Melanie Avalon: So, what happened with the bison?

Evan DeMarco: So, in an effort to really-- it was a war against the American Indians are the Native Americans and so we went in and the army at the time was charged with slaughtering millions and millions of the native bisons. And what that did was that forced the Native Americans into an agreement with the American settlers, and then from that point on we push them into their tribal lands. But yeah, one of the greatest tragedies in global history is what the American settlers did to the bison and we hunted them almost to extinction. But there are pictures of just mountains of bison bones. And it's just the American army at the time was charged with killing as many as they could.

Melanie Avalon: Oh, my goodness, that is really haunting. Okay, you mentioned the role of the soil and how it is affected by these animals. There's this fact that's floating around out there. But then I heard that it's not based on reality. I don't even know what the actual fact is. But they say we're losing our topsoil in X amount of years, it's going to be gone or so what is the state of the topsoil right now?

Evan DeMarco: it's a damn Greek tragedy. Now, in 2015, the World Health Organization in conjunction with the United Nations proposed, through some reports said that there were about 60 harvests left on planet earth that was later debunked, but what it basically said is, is that we're eroding topsoil to the point that there's really only 60 viable harvests left on the planet at that point, since we would no longer be able to sustain agriculture, it would be considered an extinction-level event for the planet. That has been debunked. But as we look at the science and especially here in the United States where we have the largest prevalence of use of herbicides, fungicides, and tilling, those numbers are not outside of the realm of possibility, and I've heard some science say, 100 to 120 years at the current pace, what we do know is that the microbial quality of the soil, basically everything that is soil health, water infiltration, carbon sequestration, all the things that we know lead to that soil health, is eroding at such a fast pace, that we can't quantify how much time is left at the current pace. But what we do know is that what we're doing through monocropping, through the application of pesticides and herbicides that we are creating a soil that will be completely unsustainable in realistically the next two generations.

Melanie Avalon: Wow and going back to what you're talking about earlier about technology and the role of technology and all of this, I can just see some brainstorming people on the plant-based side of things, proposing that there might be a way of technology to regenerate the soil, is that at all a possibility? Or can it really only happen organically or naturally?

Evan DeMarco: I don't know of any technological means that's been proposed that would allow for the soil to regenerate other than the application of ruminant animals and going back to the way that it once was. And that, unfortunately, is not in line with, the typical plant-based ideology. But here's the question, these animals existed long before humans showed up. And if we play our cards right, these animals will exist in concert with humans for generations to come. But my question to that plant-based population is what are we supposed to do with these animals? If they are not for the harmonious and oftentimes, "Circle of life" component of our part here on this planet then what do we do with them? I have never been able to get a good answer from, shall we say, the plant-based population. But to answer your question on the technology, I do not know of any technological intervention that would allow us to do what naturally we can do with just allowing cows and bison and other ruminant animals to do what they do best, which is to live in concert with the planet.

Melanie Avalon: I was thinking more growing plants in greenhouses and providing, I don't know just inserting nutrients, just recreating the environment ourselves.

Evan DeMarco: We can, and here's where it gets funky, I'm a big believer that hydroponic or plant-based vertical gardening is going to have to be an essential component of our diet as populations continue to spiral out of control, we're at close to 8 billion. Some of the reports suggest that we could be at 10 to 12 billion in the next 10 to 15 years. Those are staggering numbers, so theoretically and especially with what we're doing to the environment, some of these vertical gardens, some of these kinds of concepts are going to be essential for us now. I actually like them for a couple of different reasons. Growing your own food is one of those things that allows us to reconnect with our food supply. One of the great stories was COVID happened right and we had no clue what was going on. So, it's like is this the end of the world? Is this a zombie apocalypse what's going on? Me trying to at least be somewhat prepared, I go to Home Depot and I buy all of these plant seeds and all of these, basically how to grow food at home. That was almost three years ago and I have yet to produce a single edible thing. What it taught me was, again, how disconnected we are from our food supply. Food waste in the United States is atrocious what is it? 800 billion tons of food a year, 80 billion tons of food a year, I guarantee that when you grow your own food you waste a lot less. As we start to look at some of these solutions, these micro solutions for food scarcity for domestic food security, some of these things are a great opportunity for people to get more connected with their food supply, wasteless and be a little bit more health conscious by making sure that they're growing organic fruits, vegetables at home. I think that there's absolutely a place for this, that technology should not be relied upon as the single source of, shall we say, plant-based ideology for ensuring that we can feed 8 billion people. And if you do the back-of-the-envelope math, if the entire 8 billion people on planet earth were to switch to a plant-based lifestyle, we would eradicate the soil in less than a decade. So, think of it this way, if 8 million people switch to a vegan diet today, the planet would be inhabitable in 10 years.

Melanie Avalon: Do you know when they're planning potential? Well, not that we're going to do this, but I know they've done studies on food systems if we were to live on another planet, are those usually all hydroponic-type situations? Do you know?

Evan DeMarco: Yes, and it has to be, but one of the things that most of those food systems, those concepts, and I know that actually, Elon Musk's brother is working on this as part of the SpaceX going to Mars thing. What they haven't been able to reconcile is the nutritional deficiencies of a hydroponic plant-based lifestyle with what the physical demands are going to be of working in a place that. Muscle-protein synthesis, muscle-protein breakdown seems to be one of the most common occurrences that happens as we start to evolve into a plant-based lifestyle where the lack of animal protein becomes a real hindrance to a mission, a long-term thriving environment on a foreign planet.

Melanie Avalon: Well, it's that really famous biosphere study that I don't remember, was that in the 80s or the 90s when they had people live in this--

Evan DeMarco: The biodome.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, like a self-sustainable and they had to grow their own food, they were in there for a long time, it really ended up being a really good look at calorie restriction, the health effects of that because they ended up very calorie-restricted.

Evan DeMarco: They did and I think they had to pull the plug early. It actually ended up being an epic failure.

Melanie Avalon: And I know, one of the main guys actually died prematurely. And I think it might have happened due to the effects of that. So, interesting about the pandemic and growing your own stuff and all of that. So, I have a lot of AeroGarden units and I grow, I'm looking at it right now, I grow cucumbers, and chives, and cilantro, I had never grown anything like not extensively, at least not actual things I could eat before. And an interesting experience I had doing that, A, I recommend everybody do it, not necessarily to feed yourself although that could be a good reason, but more just what you are mentioning, having this experience of connecting yourself to your food and what it's to grow something. Something, really interesting about it, and this ties into, we haven't talked about this yet. But I guess the ethics surrounding eating animals and all of that. When I finally grew my own cucumbers, I realized these plants feel very alive to me. And I don't want to say they're sentient, but they feel very much alive. It made me ponder because there's a lot of arguments from the vegan side about the ethics and morality of eating animals, eating sentient beings. But to me it seems everything is alive and maybe we should look at the natural circle of life Lion King style. What are your thoughts on those arguments that are presented about the morality and ethics of eating animals that were sentient?

Evan DeMarco: I think it comes back to for something to live, something has to die. And that is the circle of life, that is the way that this planet is based, and whether that's from the lonely fungus to the worm, to the larger animal, for something to live something has to die. And when we ignore that and when we think that we exist outside of that that is the greatest acme of foolishness in all of human history. And that is what I challenge the vegans to recognize is that how do you exist outside of the food supply? How do you exist outside of the food chain? And just because we evolved as perhaps arguably the dominant species on this planet, does not give us the right through some small simple twist of evolution to think that we can exist outside of that. And what happened in this weird evolution of man is that we forgot that being can be connected to our food supply, being connected to the animals that nourish us more so than the plants because if we go monocrop anything or monocrop land, we kill a lot more in that acre of monocrop land that ever will happen when we kill a larger animal. But when we start to exhibit gratitude, and connection to our food supply, whether that's blueberry or a cow, then we're reconnected into this lifecycle and we start to shed the ego that I really believe a lot of vegans have is that they think that they can exist outside of the food supply, and you just simply can't. In doing so, you create exponentially more harm, then to acknowledge what it means to be part of that holistic environment.

Janna Breslin: One thing that I think is very interesting too is that children these days as well, I've noticed that there are a lot of school programs that are integrating more farm day trips, where they bring kids to farms and get them more connected. And I think that is something that we are missing in today's world. Me personally, I am very spiritually connected to animals. I love animals so much. And when people do hear that we own a processing facility where we do kill animals, it can be very conflicting. How can you say you love animals when you do this for a living or for work? I have a story where the first time that I went to our processing facility, it is different. If it's not something that you grew up with where you are in a ranching family, or you're on the farm, or you work with animals, or you eat the animals that are on your land, it's very different when you come from a city, and you're not used to seeing what the actual process is like. For me coming into that type of environment for the first time when we started this business it was very shocking to me, but afterwards I have never felt more connected or have had more reverence for animals before then. So even just acknowledging the process of what we do to nourish ourselves with the animal protein that we eat, it actually has enhanced my love and appreciation for animals more than I thought that I could have. And I do appreciate that there are programs especially with the children, we are integrating more of this, get back to your roots, get your hands in the soil, be with animals and get outside. I think that will be a very amazing step forward to us getting more connected with our world especially starting at such a young age for children.

Melanie Avalon: Do you get a lot of backlash? Or do you get threats or anything like that?

Janna Breslin: Oh, yeah.

Melanie Avalon: Regularly?

Janna Breslin: Yeah, absolutely. I mean with my following on social media, as well, I'm sure it's just the social media world is very opinionated, and people are hiding behind keyboards and stuff like that. And so, you pair that with the very opinionated movements between eating animal-based versus, vegan or plant-based. Yeah, they definitely come out, and we have definitely gotten some very, very aggressive insults.

Evan DeMarco: And I make no mistake about it that if you look at my social media, I to poke the vegan bears, I like to say, and I hate that it's become so polarizing and the fact that we can't have academic intellectual debates. But when an ideology is based off of a belief system and not science, it's religion, how do you change people's minds? But the interesting thing that we found and I don't know, if you've seen this is the number of vegan, ex-vegans who have said, you know what, I changed to a vegan diet for health and then it worked for a little bit, but then I was so unhealthy afterwards that I had to reintroduce animal protein. And, I work with a lot of doctors, I think a lot of people who've been great guests on your show say the same thing, it's that the vegans are actually their most unhealthy patients. So, it's really balancing the ideological ego that says, "I can exist outside of the food supply," with the real health and needs of incorporating animal protein into a diet. And we just haven't been able to reconcile those two especially in social media where people, as Janna said, like to hide behind their keyboards.

Melanie Avalon: It's shocking what people will say it's if you saw him in real life, I mean, most people would not go up to you and say that in real life, it's a really sad state of affairs. And the protein piece I just think is, well, there's a lot of confusion surrounding that as well. And I think people will make it very generalized and basic. People will say, "Oh, you can get enough protein easily from plants that it's not difficult to do." But it doesn't take into account the fact that I think a lot of what we base it on is ruminants, where they have the ability to turn plants into protein, more so than we can, I was listening to an interview about this recently, and they were talking about the gut microbiome and cows for example on how-- literally they can create amino acids from that that we just can't. So, any studies based on looking at animals that eat grass and the protein that they make from that, vegetarian animals, it's just not the same thing for us. Do you think it's possible for any vegans to get enough protein? Do you think there are some outliers or across the board is it an issue?

Evan DeMarco: I think there's always going to be outliers. And, obviously if something's working for you, great, but I think that we can't look at the microcosm of a short amount of time in a vegan diet as the answer to everything. And what we found is that people who've had health benefits on a vegan diet are usually coming from the standard American diet where they're so full of seed oils, high omega-6s, and, potato chips and sugars. Well, yeah, if you eat anything natural after that you're going to be healthy. But sarcopenia or muscle protein breakdown especially as we age is a very, very real thing and that jump-off-the-cliff moment is when we can no longer synthesize muscle protein or amino acids for that muscle protein. And we start to have that real cataclysmic breakdown. I have seen in most of the literature, actually, in all of the literature that muscle protein breakdown or sarcopenia is exacerbated by a vegan diet. We know that with clean protein, animal protein, we can actually live a longer healthier existence. The challenge is the argument is that well red meat is so bad for you. But most of the time that was paired with that standard American diet of seed oils of high omega-6s, of things that really didn't look at protein from an animal in isolation as its health benefits without combining it with all the things that we now know are so toxic to a human being.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, I cannot agree more. And the healthy user bias I think is just so rampant. Basically, the fact that a lot of people that are eating red meat, you just said, it tends to be a certain type of person just if you're looking at the whole entire general population that is more in line with a more standard diet compared to people who aren't who are likely following a lot of other healthy practices as well. I think it's just pretty blinding, I know that they've done interesting studies where they control for that by doing it with populations that shop at Whole Foods or something. And then I'd have to find the exact study. But basically, the differences go away, when you select people who are purposely following a healthy diet, it's harder to make those connections with red meat specifically and health issues. Speaking of nutrition and all of this stuff, how do you feel about the nutritional profile differences and benefits between conventionally raised meat versus sustainable, regenerative, we probably need to define organic. I've had Robb Wolf on the show multiple times and he wrote a beautiful book called Sacred Cow, which I really, really recommend that everybody read. He actually makes the case in that book, surprisingly, that regeneratively raised and sustainable and grass-fed, grass-finished beef actually isn't that much more nutritionally better than conventionally raised? What are your thoughts on that?

Evan DeMarco: Yeah, obviously he and Diane, I think, have done a lot of research on this one. And it's hard to ignore the commitment and really the opportunity that they've given the regenerative movement to capture a foothold in the marketplace. We absolutely love what they've done and applaud that. Now. I'm going to take a step back in time and look at what happened in the 1960s when Dr. Jörn Dyerberg went to Greenland to study the Inuit population to determine why they as a subset of a population without access to fresh fruits and vegetables had such a lower incidence of cardiovascular disease than almost any other subset of the population. After his time there and taking all these blood samples in the study, he comes back and publishes his findings. And what he found is that their predominant dietary staple was whale meat or seal, which was really high in omega-3 and really low in omega-6. And so that was really the beginning of this whole omega-3 movement. And at the time, there wasn't really a viable commercial source of whale or seal oil to create that. So, that's where the world turned to fish oil and we saw the giant explosion of the fish oil boom especially on the EPA side, which we now know is essential for some cardiovascular health.

Well, basically, what we found is that the omega-6 to omega-3 ratio was the driving force in those inflammatory components that allowed the Inuit population to not have the cardiovascular disease that especially Americans had. If we think about the omega-6 to omega-3 ratio from an anthropological perspective, about 150 years ago, most people on the planet had about a 4:1 to 6:3 ratio, which modern science says that's pretty optimal for balancing inflammation resolution. Now it wasn't until we started to get into the seed oils, especially the corn and all of that that those numbers went from a 4:1 to a staggering sometimes 25:1 here in the United States. That level of omega-6 is so proinflammatory and oftentimes is blamed on red meat when in fact it's mostly the seed oils, the corn, the grain. So, then theoretically and through science, what happens is if we're pumping all of these cows full of that same corn, that same grain that has such a high level of omega-6, that ruminant animal is not capable at that level of separating out those omega components. And so, when we eat that animal, we are getting more omega-6 than we would from a traditional or from a more regenerative or holistically managed animal. And while Robb's research is correct, in a lot of ways what I found is looking at the Omega quant testing the pmega-6 to omega-3 ratios of regenerative cows versus conventional cows that are fed that grain diet, we can see that there is a significant health benefit from a regenerative cow simply in the lower omega-6 ratio. And when we extrapolate that to a better diet, we can see that lowering that omega-6 has a profound health benefit for everybody. Now we have more optimal ratios, we have better inflammation resolution, we just have lower inflammatory markers. And if inflammation is really the root cause of all disease, anything that we can do to keep that down is completely beneficial.

Melanie Avalon: I'm so glad you said that because he talks about that in the book and I actually have my notes from the book that he wrote about with that because he was saying, I hope this is the right numbers, I have written down from that book that conventional the omega-6 to omega-3 is an average of 67:320, compared to 14:24, grass-fed grass-finished. And what I thought interesting was it's been a while since I read it, but I think in that section, he was saying, "Well, that the omega-3, omega-6s aren't a large portion of the fat anyways, it's not that big of a deal because it's more the mono unsaturated fats in the meat. And that you could get the omega-3s from salmon, but the way I see it is I don't think we need massive amounts of these omegas in our diet, but it's the ratio that's so important. And if the foundation of the meat, even if it's not your main source of omega-3s, if the foundation of it is so skewed in that direction with the Omega-6s and that's the foundation of your diet. I think that that could have, as far as setting up the inflammatory profile of your body, I could see how it would have really big implications. I'm glad you said all of that.

Evan DeMarco: Absolutely and I couldn't agree with you more, Melanie, I think that's something that we have to consider and really looking at what we've done to our oceans, it's unfair of us to now be dependent on fish, fish oil, those type of omega-3s to counter what we've done by feeding our cows massive amounts of omega-6 when we can just solve the problem by turning all of these cows loose on open fields on open pastures on the grass, which allows us to regenerate the land, to reverse climate change, to reverse desertification, to improve the soil, all the things that we know we need. The simple solutions are so elegant, yet so profound in their ability to undo all of the damage that we as a species have caused, it's like why do we even need to think about fish, if you want to have sushi go have sushi, but let's not look at that as a solution. Let's look at that as an element of a diet assuming that we can get our land back to where it needs to be and our oceans back to where they need to be, so we're not eating plastic fish.

Melanie Avalon: So actually, to that point, I actually have I think at least in my world controversial thoughts on the whole fish thing. So, many people are-- they say to eat all wild-caught fish. I am so concerned about the toxins in our ocean that I actually only eat-- I vet the fisheries where I'm getting my fish from and I actually prefer farm raised where it's very sustainable and it's monitored for toxins and mercury levels because even wild-caught salmon I don't trust with mercury and toxins.

Janna Breslin: Evan and I actually, we probably eat fish maybe once a month now or something, it is not anywhere near what we used to eat, and actually I've had mercury toxicity for years and I've done a lot of work on my own to get rid of the toxins that I know for fact were coming from the fish I was eating, which was a lot at a certain point. Our oceans are not healthy and we're very skeptical of-- the fish can't run away from the toxins, they're breathing it in, they can't help but ingest what we're putting in our oceans. Because of that, now, we are ingesting that. And that is not, we should be skeptical, we should be more mindful about where we're actually getting our fish and where we're getting that from. We've almost cut fish almost entirely out of our diet and focus more on our ruminant animals, eating more nose-to-tail to get as many nutrition as possible.

Melanie Avalon: You mentioned earlier, Chris Shea, did you work with him on your heavy metal toxicity?

Janna Breslin: Not him specifically, but yes, we're very close with Chris and he's definitely given me a lot of different protocols and things that like in the past. He's a fantastic person.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, I remember when I had him on the show. I mean, I had mercury toxicity as well. And he told me I would be on his wall of fame. I was like "Oh, no." [laughs] So, my blood levels were 30-something, which is not good.

Janna Breslin: Yeah, my doctor also told me it was off the chart. She's never seen anyone as high as mercury as what I did. So, I did chelation therapy for two years, saunas, coffee enemas, I did so many things to help detox.

Melanie Avalon: Me and you both? [chuckles]

Janna Breslin: Yes, so many things help detox the body. And it is a long process, I mean, we have to be mindful about what we're consuming. And we live in a toxic world, the world that we live in now is out to kill us really. We have to do things to combat the toxins and things that we're exposed to on a daily basis that we can't run away from. This is our water. This is our air. These are the things, our household supplies-- this is a whole other topic, obviously. But it's so important, I know, you understand?

Melanie Avalon: I actually can tie it into our present topic, but just out of curiosity. Did you do pharmaceutical chelation?

Janna Breslin: It was an EDTA supplement that I was taking on almost a daily basis. So, it wasn't the IV drips. I know some people get it was more of a supplementation that lasted about two years.

Melanie Avalon: It was EDTA or it was not?

Janna Breslin: Yes, it was.

Melanie Avalon: Oh, it was. Oh, wow, you took oral EDTA.

Janna Breslin: Yeah, it's a company called zymogen.

Melanie Avalon: Wow. Okay. I've heard of oral DMSA. I didn't know people could do EDTA orally. I did IV and I think looking back and I would not have done it. Because I'm an extremist and when I found that out, I was okay I was getting this out. I'm just going to do these IVs on a pull all the metal out. And I think I went too intense and pulled out a lot of nutrients.

Janna Breslin: Gotcha and obviously, if you pull too much, if you stir up too much toxin that's in your body that can cause some other reactions as well. So, it is a slow process unfortunately like I said it took me two years to fully get rid of them. So yeah, but once you know what real health feels like, you're like damn, I didn't know I was this sluggish or my mind wasn't right all the time, or I couldn't think this well. And once you actually feel what health feels damn, alright this is something I need to continue.

Melanie Avalon: The saunas really helped and that's a daily part of my life now. I just love it so much.

Evan DeMarco: But do you do cryo?

Melanie Avalon: Everyday?

Janna Breslin: Oh, good, awesome.

Evan DeMarco: Nice.

Melanie Avalon: Every day I can. I'll go right after this, do you guys do cryo?

Evan DeMarco: Yeah, interestingly enough, this was probably about two years ago as COVID was starting and we've always really been into sauna or contrast therapy. And, it's COVID, well, we're not going to go to the clinic and do it. So, we started looking at some of the options and I just didn't like any of them. They all look like pine death boxes. So, we decided to build one just for our own use, and I built it out of copper and it was just this really beautiful-looking tub. And then everybody's is like "Oh, you should sell that." So then, I'm like all right, yeah, I need another project. So, we actually created our own cryotherapy tub but it's all reclaimed wood using just natural products and I use copper because I wanted something that wasn't chemical base. I wanted a natural metal that would clean water very, very well without any chlorine or anything like that. So yeah, we actually built and started selling our own Cryo Tubs.

Melanie Avalon: You put ice in it?

Evan DeMarco: No, it's self-cooling, so you just plug the thing in it.

Melanie Avalon: Oh, okay. It does plug in, "Oh wow, you guys are inventors.

Janna Breslin: Self-cleaning, self-cooling unit? Yeah, we to do many things. [laughs]

Melanie Avalon: That's so cool.

Janna Breslin: Yeah, I go to restore and do the chamber.

Melanie Avalon: Oh, like the chambers, right?

Janna Breslin: Mm hmm, yeah. I need to do the actual water. You know what's interesting, I found that getting into ice water is a lot more challenging than stepping into one of the cold chambers and it's a different mentality I think to submerge yourself where every inch of you is covered and 40 degrees or whatever, maybe lower.

Evan DeMarco: When I think the brown fat activation on water submersion over the liquid nitrogen cold chambers is beyond debate. So, it's a lot more painful. But I think the benefits far outweigh the pain.

Janna Breslin: Yeah.

Melanie Avalon: I believe you. Like I said, I haven't actually done an ice bath which probably shocks a lot of my listeners, but I can just tell, I know that it's probably way, way worse. [laughs]

Evan DeMarco: Oh, it sucks. It's brutal.

Melanie Avalon: I had Wim Hof on the show as well and that was one of my most amazing interviews ever. And I was asking him if I could get a chest freezer and fill it with water. And he was like, sure. [laughs] I need to get on that.

Evan DeMarco: We love Wim, we had him on our show. And same thing, he's so passionate.

Janna Breslin: Such a beam of light, just a beam of light. He's incredible.

Melanie Avalon: When I was mentioning Farmer Lee Jones earlier, he has that same spirit. Wim too, have been the two interviews where I was literally just like "I was beaming and smiling the whole time, because I just felt so inspired." But actually, I am glad we're talking about toxins. So, the role of toxins and conventionally raised livestock, how bad is that? Hormones, antibiotics, all of that stuff?

Evan DeMarco: It's pretty bad. And we also have to consider the food supply of the animals. When we look at these large feedlots, which are owned predominantly by the big four meat producers, places like Colorado or Nebraska, or even South America, where we're seeing a lot of deforestation. The genetically modified, covered in glyphosate corn is what's being fed to these animals. So, you have that level of toxin but then for the purposes of maintaining that animal through its lifecycle, you have the hormones and the antibiotics. And there's this one-two punch of what conventional meat is doing to us. And it's scary, let's be honest, I mean, when we're imbibing those toxins, we're imbibing those hormones and antibiotics. It is completely foolish to think that that doesn't have some type of impact and now if we're promoting a meat lifestyle or more meat in our life because of the nutritional benefits, but then we're offsetting that with these conventional raised beef, it's no wonder that we're seeing a lot of the health ramifications, especially in what we would consider the lower socio-economic groups who can only really purchase some of that cheaper meat.

Melanie Avalon: Do you guys know Teri Cochrane? Have you met her?

Evan DeMarco: Yeah.

Melanie Avalon: She has a really fascinating theory. She thinks that the stressful conditions of conventionally raised livestock actually causes the proteins in them to truncate and create these amyloids and she thinks that's a key factor in health conditions. Do you guys have any thoughts on that?

Evan DeMarco: Absolutely, and actually there's a company out of Greeley, Colorado that we work with are called Xiant and I'm not allowed to share a lot of the information, but what they've done is create red light or light devices. But those light devices are actually pulsed at specific recipes to create certain physiological responses. What we do is we utilize those lights when we transport cattle from the farm to the processing facility. And what we've been able to--

Melanie Avalon: Calms them down?

Evan DeMarco: It calms them down to the point that their melatonin levels stay ridiculously high, while their cortisol levels stay ridiculously low, so far different than the control group. And that light by mitigating that stress, it obviously has a better impact on the quality of meat, but it's also a better impact on all of the elements of that animal. And what we're seeing is now we're starting to put these lights in the farms, in the ranches and so these animals are exposed to this constantly. And it mitigates a lot of the stress responses that they have. And these are even just natural free-range cattle. But we're seeing it at some of these smaller feedlot types of areas. This technology has also been used in egg production. And what we're seeing is, is the egg production is so much better, so much healthier.

Melanie Avalon: For chickens?

Evan DeMarco: For chickens. Yeah, so it's the ability, I come back to something I said earlier is the ability for technology to have an impact in agriculture is there and we just need to embrace it and recognize that we can have a profound positive impact in the entire food supply by utilizing some of these new understandings.

Melanie Avalon: This is sort of a controversial question. So, I had Mark Schatzker on the show, he wrote a book called The Dorito Effect and the End of Craving. Those are two different books, but then he wrote a book called Steak. Have you guys read it?

Evan DeMarco: I have not.

Janna Breslin: No.

Evan DeMarco: Just added it to the list.

Melanie Avalon: He basically went around the entire world to try to find the world's best steak. I learned so much about the different types of cattle and the different types of steak and it's fascinating, and I learned all of these crazy fun facts I didn't know like Black Angus Beef, they basically just-- if it's a black cow, they basically label it Black Angus, but it might not be. I was mind blown, that's so arbitrary. [laughs]

Janna Breslin: It's literally just the color of their hair.

Melanie Avalon: And they might not even be Angus. [laughs] So, it's a really funny book. But in any case, the last chapter, I think is the last chapter. After going and doing all of this, he decided to raise his own cow just for the purpose of that experience and seeing what that was like. And then having his own steak from a cow that he raised. And at the end, I was laughing out loud reading it, but he talks about, it's kind of dark, but he was talking about the moment where he had to prepare the cow to take to the slaughterhouse and all that. And she had a name and everything and he was giving her beer and apples and trying to make her feel really good. So, my controversial but actually sort of serious question, can you get the cows tipsy? Will they be happier? I'm just wondering about substances and stress levels of the animals, you're using the red light, obviously, but are there other methods to reduce their stress at the end?

Evan DeMarco: I think so much of it actually comes down to how they're raised and the stress level of a cow that's raised on pasture, on grass is so much less than these confined animals. And that's a big part of it right now. One of the things that we've been able to do is mitigate some of the stress of the natural world through the use of cowboys or holistic management. Think of it this way, if the cows are out in pasture their entire life, well, natural predators cause a natural stress response. So, you've got wolves, you've got whatever natural predators and so that animal is always on heightened alert, meaning its cortisol levels are always a little bit higher because it's always prepared for fight or flight. If in the process of holistic management, we're just utilizing electric fencing and cowboys to move them along, they have that same free range, but they have a lower cortisol level because they're not constantly freaked out about what's around the corner.

So, really when we talk about animal husbandry it's just free range. It's getting these animals out on pasture, moving them through, giving them a quality of life that they didn't have either in the feedlot or even before the revolution of regenerative agriculture. So, this is that thing. If we're going to have animals out on the pasture, which we need, we can't eliminate animals from the planet. What's better to have this animal live this amazing life out on pasture, eating grass, feeling safe because it's got the cowboy there with the six-shooter or to be constantly on edge because it thinks that it's going to die that day from a wolf or a bear or something like that? What's better? Is it better to give these animals an amazing life to honor that animal and then at the end of its life to honor it even further by being connected to that animal as a part of our food supply, eating all of it, nose to tail, the organs, everything. And if for whatever reason we don't eat it, we utilize that. And that's one of the things that we've done at our processing facilities. We have an aerobic digester, so anything that's not edible goes into this digester and 24 hours later comes out as organic fertilizer that we now share with ranchers and farmers in the area, so that they have a cheaper source of organic fertilizer to help continue that cycle of life. And now we know what's happening in Ukraine and Russia, fertilizer prices are through the roof, grain prices are through the roof. By taking control of that entire value chain and utilizing every bit of that animal the way that our ancestors did, we're able to really reconnect with all parts of how it means to be human.

Melanie Avalon: So basically, these livestock and these animals are-- they can if they're in the system, living a better life than they would be in the wild. I guess the argument that I'm just thinking like devil's advocate and feel the argument that the vegans can make or an analogy would be, this is a very dark analogy, I'm trying to stop if I should say it, I guess the analogy would be if it was a species above us, raising humans, and it was either the option of letting humans be on this world and in war and fighting themselves and having strife, but they had agency over their own ultimate ending based on their life choices, and what wars they're engaging in and what predators they escape or don't compared to like having the species, us on a planet and take care of us. We actually don't have danger and threat and everything's good, but then at the end, they kill us.

Janna Breslin: That is a very interesting thought. [laughs] Evan have you ever thought that before?

Evan DeMarco: Well, I mean, look we always talk about it in the form of if an alien civilization comes down, always the technologically inferior civilization is the one that gets eradicated. So, do we honor our position when I say position on this one, I think it could be debatable as the dominant species on the planet and recognize that to get to that dominant species, we integrated animals as part of our food supply. If we acknowledge that that's how we got here, is it up to us to continue that process in a way that benefits both the animal that got us here and our new position as the dominant species on the planet? I don't know and this is the ethical debate, but I love it from the standpoint of saying we cannot now say that because of where we're at from an evolutionary standpoint, we can no longer look at other animals as part of our food supply. If we consider ourselves apex predators, which we are, then how does that work, I think that the humanity in us is to say that we are now offering or giving that animal a much better existence than what it would have had 100 years ago when it didn't just have to worry about us, but it was wolves and bears, and I'm sorry but as Janna said, when you come to a processing facility, it's not glorious work. It's not being a porn star if that's considered glorious work. That was a joke. It's difficult, it's challenging. The people that work at these plants have a level of compassion and understanding for these animals that I never would have believed until I was there. What is better for that animal to live an amazing life and then to become part of our food supply in one instance with a piece of technology that kills it quickly, instantaneously, or to be taken down by a wolf or a bear where it's slowly consumed being aware of almost every moment of that demise.

Janna Breslin: it's one bad day versus a lifetime of potential threats and disease and could be slow deaths, injuries, broken legs, where there just-- it could be suffering, and yes this is a very ethical debate and Diana Rodgers actually did a really interesting post about this a while back about animals that really, truly are just living out in the wild, where we're not helping manage them, their deaths can be very slow and agonizing if they're not being treated, or they're very safe with people, and then they have one bad day. And it is this weird, ethical trade-off and you think about, what is the most appropriate thing to do? And I like the whole one bad day thing? That sounds a little bit better to me.

Melanie Avalon: Are they stunned?

Janna Breslin: How does the process work?

Melanie Avalon: Yeah.

Evan DeMarco: So there's a couple of different ways, mostly it's a bolt gun, it's just an instantaneous death. And the US Department of Agriculture is onsite for every single event and they monitor and improve practices all the time to ensure that these animals do not suffer. And we can say that and I'm sure that every vegan out there is "Well, how do we know?" The answer is we don't. And the real challenge is to not focus on that moment but to focus on the food supply, and to really be grateful and have gratitude for that animal knowing that we're doing the best that we can with our understanding of the tools to ensure that moment is as quick and as painless as possible. I'm not going to say that it's completely painless because I don't know and I don't think anybody does. But it's really a recognition that if we are connected to that food supply, then we can be grateful for that animal. And then we can utilize every bit of that animal to perpetuate a healthy existence for us and for the planet.

Melanie Avalon: I mean, going back to what you're talking about, with the evolutionary progression of us as the apex predator and that journey involving eating species below us, I think it would be one thing if a completely plant-based system actually could support health in the environment. I really just think that's a pipe dream, especially reading Robb Wolf's, Sacred Cow. I mean, it just seems that is just a disaster for the planet, and health, and humanity. People like to just look at things very black and white and not look at the details of everything. And I think that does a disservice to everything. I think one of the biggest arguments for just the natural circle of life is there are carnivorous mushrooms and so what's going-- is that okay? if mushrooms can eat other plants, I just think people should think about that.

Evan DeMarco: Oh, yeah. And let's look back at the entire evolutionary history, the anthropological history of this planet, it's the same thing, it's for something to live, something must die. If you have your herbivore species, you have your omnivore species, you have your carnivore species. Human beings exist in that omnivore stage, but when we really look at it, and I don't know how this, I want to throw them under the bus, but if you go to PETA's website People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, they have something on there that says that if you're driving down the road and you see an animal that was run over and died on the side of the road and you don't feel compelled to go eat it, that scientific proof that we evolved as herbivores. And I'm like "Oh, I lost my mind, my head is like almost exploded."

Janna Breslin: Very strong statement.

Evan DeMarco: And PETA, let's be honest has never been known for being smart. They've been known for being good marketers. But what we do know is everything about human evolution, human biology dictates that we evolved as omnivores, we utilize plants, we utilize berries and vegetables as an interim nutritional source while we were as nomads tracking down large game and our gut microbiome, our teeth, our jaws, all of these things dictate that, yes, we are omnivorous, we get protein, we can synthesize protein from animals, and actually to the fact that our gut microbiome actually puts us more as scavengers and less as carnivorous meaning because we didn't have the strength or the ferocity to go kill the animal, oftentimes, we would come in and pick up the carcass, right, we would eat the stuff that was left over after the lion was done with it. It's impossible to ignore our evolution. And in that, why do we think that we shouldn't continue to perpetuate that type of lifestyle for optimal health?

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, you mentioned, I think this is something probably important to define for listeners, you mentioned the word free range. And we've been using a lot of words like grass-fed, grass-finished, free-range, organic. What do all of these labels actually mean? Because I know when you go to the grocery store, there's all the labels. And what's the difference between grass-fed, grass-finished, grass-fed, forage-finished, there're just so many things.

Evan DeMarco: Oh, my God, yes. And it's all marketing. It is literally all marketing. All cows are grass-fed. I mean unless a cow is born in a feedlot and pumped full of corn, at a certain point the way that our cattle system works is most cows are born out on the way out in the range. And so, they're grass-fed, every cow is grass-fed, it's how they're finished. And so that's really where we need to pay attention to the vernacular on this one, grass-fed and grass-finished is ideal, grass-fed forage-finished is okay, forage is really this, it can be regenerative, but it can also include some grain. So, if we really liked the idea of regenerative, it's grass-fed, grass-finished regeneratively raised. And then of course, most of the time, if you're just buying the cheap beef at the grocery store that's going to be grass-fed, grain-finished in a feedlot, no hormones or antibiotics is something that we should always be looking for. And I think when you get into this free-range or cage-free all that really gets more into the chicken side of things. But that's a whole other bag of kittens that's worth unpacking because the marketing behind that is pretty deceiving and honestly scary because we think about cage-free, well, cage-free is a violent place for chickens to live.

So basically, cage-free means that they're all in this warehouse. They're not in cages, but chickens are violent animals. And what happens is, they're just constantly killing each other. Free range is they're out of the cage, they're in the barn, and they have access to the outdoors. But what happens is that most chickens won't actually take advantage of that access. So, there'll be a door there that they can open, almost a dog door. But most chickens will never take advantage of that. And so, what we really start to understand is the marketing and all of this and there's some great articles online just to understand the language, and then make decisions based off of what's best for the animal and for us as people. And that's where we just have to understand this like we need to shop with our wallets in the sense of incentivize all of these producers to create food or to get us food that is in line with what's natural, what's best for our environment, and what's best for our health.

Melanie Avalon: I'm so glad you said that because this is a huge question I have and I've actually-- I think about it a lot. Every time I'm at the grocery store, I've pulled my audience and the results are always-- people have a lot of opinions about it. How do you feel, because a lot of the big chains like Target and Kroger and I don't know in Sacramento, what they have if it's Ralphs or I'm not sure what version of Kroger you have there, but they'll have their in-store line where they say it's organic grass-fed grass-finished. People will say that's not a good thing because that's industry taking over and that it's not going to be as transparent as it should be. On the flipside, people will say no that what we need, its big companies moving towards this movement. So, how do you feel about the large companies doing this and having their in-house brand of, where it says that they're doing these things?

Evan DeMarco: I think it's a bad idea. And I don't think it's a bad idea from them actively getting involved in promoting the education of it. I think it's a bad idea in the sense that we need to become more communal as a country and I think as a species, and let's go back preindustrial revolution, we lived in smaller communities. If we had to go to the market because we couldn't grow something, we usually walked there, we got movement. But more importantly, we really grew or maintained everything that was in our food supply. And I think if we can go back to this, this concept of eating like a local for war. Getting your food from farmer's markets, supporting local, really supporting them as they support regenerative practices is the way that we really start to turn the tide and all of this and whether it's Target or Kroger or any of those other companies, yeah, be a part of the education. But it's really, what happens when they're a part of that is that the producer, the American rancher or farmer gets the short end of the stick. Target is making the bulk of that revenue, their margin is the most important part of that transaction and they marginalize the producer in an effort to get that product to a consumer in a supply chain that allows them to make the most amount of money. Cut them out. Target doesn't need the money.

The American rancher or farmer who's living off of subsidies needs the money. And if we look at the entire economic chain in this one, that producer, the beef producer, the egg producer, the chicken producer usually requires a government subsidy because of how little they make. So, they sell that product to a broker, that broker turns around and sells that product to Target. Target turns around and sells that product to the consumer, that consumer has to pay taxes on that product, which then go into the government subsidies so that we can go back and pay that rancher and farmer a livable wage. If we cut out the broker and Target and we just go direct to that rancher/producer, we've optimized that entire value chain to the point that that producer now can make a livable wage without the government subsidy. And we know exactly where we're getting our food which brings us one step closer to reconnecting with our food supply.

Melanie Avalon: And two questions from that one with the local. What about the fact that there could be a lot of local farmers that aren't local to anybody? Because of where they're literally based?

Evan DeMarco: Yeah, and that's the challenge. Urban sprawl has put us in a position where we might not have immediate access to a farmers' market or something like that. But I think, by and large, most places in the continental US are going to have that. Alaska might be the outlier. There might be some parts of the Midwest just because of winters or seasonality. But if we at least begin the process of starting with that, if we at least make it some part of our food acquisition, we're starting to move incrementally in the right direction. And I think that's what it takes. It's the recognition of where our food comes from, it's the recognition of what we can do to start to move in the right direction. And then it's making those small steps. We're not asking everybody to quit smoking overnight, but start to limit all the bad foods, start to support the local person that you can support and whether that's the meat producer, the chicken producer, whatnot, find a way to become a part of the solution and not a part of the problem.