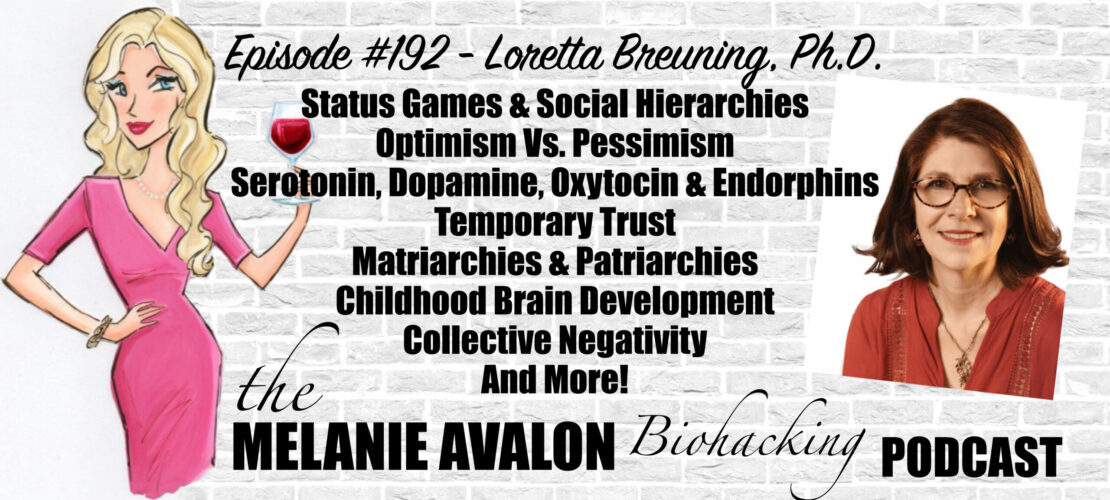

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #192 - Loretta Breuning, Ph.D.

Loretta G. Breuning, PhD, is Founder of the Inner Mammal Institute and Professor Emerita of Management at California State University, East Bay. She is the author of many personal development books, including Habits of a Happy Brain: Retrain Your Brain to Boost Your Serotonin, Dopamine, Oxytocin and Endorphin Levels.

As a teacher and a parent, she was not convinced by prevailing theories of human motivation. Then she learned about the brain chemistry we share with earlier mammals and everything made sense. She began creating resources that have helped thousands of people make peace with their inner mammal. Dr. Breuning's work has been translated into twelve languages and is cited in major media. Before teaching, she worked for the United Nations in Africa. Loretta gives zoo tours on animals behavior, after serving as a Docent at the Oakland Zoo. She is a graduate of Cornell University and Tufts. The Inner Mammal Institute offers videos, podcasts, books, blogs, multimedia, a training program, and a free five-day happy-chemical jumpstart. Details are available at InnerMammalInstitute.org.

LEARN MORE AT:

innermammalinstitute.org

facebook.com/LorettaBreuningPhD

twitter.com/InnerMammal

instagram.com/inner.mammal.inst

youtube.com/c/InnerMammalInstitute

SHOWNOTES

2:10 - IF Biohackers: Intermittent Fasting + Real Foods + Life: Join Melanie's Facebook Group For A Weekly Episode GIVEAWAY, And To Discuss And Learn About All Things Biohacking! All Conversations Welcome!

2:20 - Follow Melanie On Instagram To See The Latest Moments, Products, And #AllTheThings! @MelanieAvalon

2:45 - AvalonX MAGNESIUM NIGHTCAP: Melanie’s Magnesium Nightcap features magnesium threonate, the only type of magnesium shown to significantly cross the blood brain barrier, to support sleep, stress, memory, and mood!

AvalonX Supplements Are Free Of Toxic Fillers And Common Allergens (Including Wheat, Rice, Gluten, Dairy, Shellfish, Nuts, Soy, Eggs, And Yeast), Tested To Be Free Of Heavy Metals And Mold, And Triple Tested For Purity And Potency. Get On The Email List To Stay Up To Date With All The Special Offers And News About Melanie's New Supplements At avalonx.us/emaillist! Get 10% off AvalonX.us and Mdlogichealth.com with the code MelanieAvalon

Get 15% off during the launch (April 8th - April 17th, 2023) with code NIGHTCAP15

Text AVALONX To 877-861-8318 For A One Time 20% Off Code for AvalonX.us

6:35 - FOOD SENSE GUIDE: Get Melanie's App At Melanieavalon.com/foodsenseguide To Tackle Your Food Sensitivities! Food Sense Includes A Searchable Catalogue Of 300+ Foods, Revealing Their Gluten, FODMAP, Lectin, Histamine, Amine, Glutamate, Oxalate, Salicylate, Sulfite, And Thiol Status. Food Sense Also Includes Compound Overviews, Reactions To Look For, Lists Of Foods High And Low In Them, The Ability To Create Your Own Personal Lists, And More!

7:10 - BEAUTYCOUNTER: Non-Toxic Beauty Products Tested For Heavy Metals, Which Support Skin Health And Look Amazing! Shop At beautycounter.com/melanieavalon For Something Magical! For Exclusive Offers And Discounts, And More On The Science Of Skincare, Get On Melanie's Private Beautycounter Email List At melanieavalon.com/cleanbeauty Or Text BEAUTYCOUNTER To 877-861-8318! Find Your Perfect Beautycounter Products With Melanie's Quiz: melanieavalon.com/beautycounterquiz

Join Melanie's Facebook Group Clean Beauty And Safe Skincare With Melanie Avalon To Discuss And Learn About All The Things Clean Beauty, Beautycounter And Safe Skincare!

Habits of a Happy Brain: Retrain Your Brain to Boost Your Serotonin, Dopamine, Oxytocin, & Endorphin Levels

The Science of Positivity: Stop Negative Thought Patterns by Changing Your Brain Chemistry

Status Games: Why We Play and How to Stop

Tame Your Anxiety

13:40 - loretta's personal story

16:00 - can everyone become happy?

17:30 - how we judge our emotions

19:30 - baseline neutrality

20:50 - optimism vs Pessimism

23:30 - Dopamine

26:00 - BLISSY: Get Cooling, Comfortable, Sustainable Silk Pillowcases To Revolutionize Your Sleep, Skin, And Hair! Once You Get Silk Pillowcases, You Will Never Look Back! Get Blissy In Tons Of Colors, And Risk-Free For 60 Nights, At Blissy.Com/Melanieavalon, With The Code Melanieavalon For 30% Off!

28:45 - Oxytocin

31:25 - how we're raised

32:20 - oxytocin in animals

33:30 - the role of touch in the earliest experience

35:30 - temporary trust

37:00 - Serotonin

39:45 - motivation chemicals in plants

41:20 - serotonin in the gut; does it reach the brain?

45:40 - endorphins (endogenous Morphine)

48:00 - past experience of pain

49:00 - Idealizing the past and the future

50:00 - why does laughing release endorphin

Three Ways to Medicate Yourself With Laughter

53:40 - using humor to deal with social discomfort

57:00 - Anthropomorphizing animals

59:10 - LMNT: For Fasting Or Low-Carb Diets Electrolytes Are Key For Relieving Hunger, Cramps, Headaches, Tiredness, And Dizziness. With No Sugar, Artificial Ingredients, Coloring, And Only 2 Grams Of Carbs Per Packet, Try LMNT For Complete And Total Hydration. For A Limited Time Go To drinklmnt.com/melanieavalon To Get A Sample Pack With Any Purchase!

1:02:10 - do people like one neurochemical over another?

1:05:40 - accomplishing your goals

1:08:45 - can our addictions be good?

1:09:45 - manifesting social Hierarchy

1:14:50 - modern cocktail parties

1:17:40 - the morality of physical attraction

1:22:35 - adrenaline, cortisol & identifying threats

1:29:40 - worrying about what could happen

1:32:30 - SUNLIGHTEN: Get Up To $200 Off AND $99 Shipping (Regularly $598) With The Code MelanieAvalon At MelanieAvalon.Com/Sunlighten. Forward Your Proof Of Purchase To Podcast@MelanieAvalon.com, To Receive A Signed Copy Of What When Wine!

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #38 - Connie Zack

The Science Of Sauna: Heat Shock Proteins, Heart Health, Chronic Pain, Detox, Weight Loss, Immunity, Traditional Vs. Infrared, And More!

1:34:10 - Suffering Through The Lens Of A Lacking Mentality

1:36:10 - childhood brain development

1:38:30 - how children deal with hearing lies

1:43:00 - how our likes are related to our past

1:44:40 - psychedelics

1:45:20 - matriarchies

1:53:00 - being offended or blaming others for our misery

1:54:30 - how do we change our brains?

TRANSCRIPT

Melanie Avalon: Hi, everybody, and welcome back to the show. I am so, incredibly excited about the conversation that I'm about to have. Here's the back story on today's conversation. I received an email a while back about an author and her books and I was immediately intrigued by the topics. I knew it was an immediate yes. All I had to do was bring up the books on Amazon and immediately say yes to that, so, this author is Loretta Breuning, Ph.D. and she has quite a few books. I started with the book that her representative sent me, which was Habits of a Happy Brain: Retrain Your Brain to Boost Your Serotonin, Dopamine, Oxytocin, & Endorphin Levels. I read that book. Friends, it was fascinating. It answered so many questions. I have wondered for so long about the nuances and the specifics and the actual details about all of these "Happy hormones that affect what we do."

And so, I read that book and it was one of those books where I was just telling people everyday things that I was learning from it, and I was like, "I have to read more of her books because she has so many." So, I next read Status Games: Why We Play and How to Stop and that book has honestly changed my perspective of the world and I really mean that. It was one of those books where it's like you can't unsee it. It just showed me something I wasn't even aware of that is happening in me and happening in everybody. Not only, I'm sure we'll dive deep into this in the show, it alleviated I think a lot of concerns and burdens that people have surrounding this concept which the long story short, is the concept that social status and hierarchies and feeling the need to have social alliances and rise in society is actually all evolutionary drive and it's driven by serotonin and that's not necessarily a bad thing. So, we can talk about that. I read that and I was like, I have to read even more.

Then I read The Science of Positivity: Stop Negative Thought Patterns by Changing Your Brain Chemistry. Again, another book that just opened my eyes to something I wasn't aware of and it's funny because we can talk about this. I identify as a pretty positive person. I was like, "I didn't think I wasn't going to learn anything." But I was like, "I don't know how much this will apply to me because I feel like I'm very positive." No, not the case [chuckles]. I learned so much and we can talk about this, how I realized how I respond to events and why I'm having that response to things. It was just a really empowering book and incredible.

I was just talking with Loretta before this. Now I next want to read her book. Tame Your Anxiety: Rewiring Your Brain for Happiness. So, that is next on the list. But in any case, I have so many notes, so many questions. Loretta, first of all, thank you so much for your work and thank you for being here.

Loretta Breuning: Sure. Well, thank you so much for reading and understanding. You can imagine that I occasionally encounter people who haven't read the book and want me to explain it in 30 seconds in a way that fits all their other preconceptions. So, it's really a pleasure to talk to someone who understands.

Melanie Avalon: Oh, no, I can imagine. And for listeners, I always ask the guests how much time they have before the show and Loretta was like, "I have lots of time to dive in." So, I am really, really excited about this. For listeners who are not familiar with your work, I will let them know a little bit about you. You are the Founder of the Inner Mammal Institute and Professor Emerita of Management at California State University, East Bay, The author of all of those books that I mentioned, and there're some pretty cool things in your bio. You actually worked for the United Nations in Africa, which is very cool. And you give zoo tours on animal behavior after serving as a docent at the Oakland Zoo. You're a graduate of Cornell University and Tufts, that makes sense about all the animal stuff because one of the things that you talk about a lot in your book is "How we do compare to animals and how we didn't replace the animal brain, we just added on to it." And so we have maintained a lot of these activities and behaviors and neurotransmitters that happen in animals. Yes, so many things here. To start things off, your personal story. How did you become interested in all of this work? Have you always been interested in this? Was it an epiphany that you had one day? What's your story? Why are you doing this? Why are you doing what you do?

Loretta Breuning: Sure, well, a combination of the epiphany and the lifelong story, so when I was young, I was surrounded by a lot of unhappiness. Children absorb things and I felt bad, and I was always trying to figure it out, why is everybody so unhappy? Because there was no obvious reason. There was also social pressure for me to take on my mother's unhappiness or else I was a bad person.

I studied academic psychology. It wasn't my major. It was never my primary profession and I think that's what freed me to study every different strand and aspect of psychology rather than being committed to one paradigm, which is "What happens when it's your livelihood." Over the years, different strands of psychology came and went. Partly I saw the faddishness of it, but nothing fully explained life to me because I thought, "Okay, I'm going to do everything right according to the book of social science and then my kids will be happy all the time, and my students will be happy all the time." And guess what? It didn't work out that way.

Then I was back to square one. I'm trying to figure out the fundamental unhappiness of people. My iconic example is "Even the children of the social science professors who teach this stuff are not happy, no" So, I said, "There's got to be something missing." And I looked and looked and then when I stumbled on this mention of like "The dopamine of monkeys and the serotonin of monkeys and the endorphin and oxytocin of monkeys." And what triggers them in animals and like "Wow, I could see this is exactly what we humans are doing all the time, but we can't admit it because it's not nice." That's when I really started pursuing this. But no one else is doing this. This is not an accepted belief in academic psychology. I was really connecting the dots for myself.

Melanie Avalon: Do you feel like you have found the answer? Can everybody actually become happy?

Loretta Breuning: Yes, I think so. The simple answer is that our emotions are controlled by neural pathways built from early experience with those chemicals. My dopamine is controlled by the pathways built from my early dopamine and my serotonin is controlled by the pathways built from my early serotonin.

Now, we can change these pathways. But it's as hard as learning a foreign language, because your native language is just a neural pathway built from repeated early experience. We know that everyone is capable of learning a foreign language. But very few people do because it takes so much repetition and that's basically what it takes to rewire your emotions.

Melanie Avalon: You mentioned how you felt growing up like you needed to take on the unhappiness of your family. It's interesting because not only is there the initial question of "Am I happy or am I not happy?" Then we humans with our language brain, like language part of our brain, and I guess we can talk about that. We add on another layer where it's like we feel happy or unhappy or we feel good or bad about if we're happy or unhappy. We attach an ethical moral clause to it which is like very complicated and confusing. I actually pulled out a quote from one of your books because it was so powerful and you were talking about "People might feel like they don't deserve to be happy or something. How can it be an ethical thing if people are happy or not? Because nobody is always going to be happy and nobody is always going to be unhappy." How does it even relate to ethics and morals? Why do you think we do that? Like why do we judge our emotions on top of having them?

Loretta Breuning: First judging about not being happy is this modern thing, I call it "The disease model." That's what my new book is going to be about, which is "Happiness is the effortless default state of all humans including our distant ancestors and that monkeys are happy all the time. It's only that something has gone wrong in your world today that makes you unhappy." This is the widely shared model we have today. So, everyone thinks, "What's wrong with me? Everybody else is happy. I'm supposed to be happy automatically." But in fact, when I studied happy chemicals, I learned that they're not designed to be on all the time. Their job is to turn on in very specific moments to motivate very specific survival behaviors and then to turn off. So that they have the power to motivate you into action again when there's a survival-relevant moment, which they couldn't do if they were on all the time.

So, that's just a huge relief. It's like, "Oh, nobody is happy all the time. I'm not meant to be happy all the time. Nothing is wrong with me." But then, on the other side of the coin, I don't call it "I don't deserve to be happy." I know that's another common modern model. But the way I see it is "People think it's not nice to be happy because then you're not empathizing with the suffering of and then fill in the blank of whoever suffering you've been programmed to empathize with."

Melanie Avalon: That's the quote that I pulled out. What is our baseline state and how does it compare to animals? Is there a state of neutrality? Can you be releasing-- and we can dive into what these actual neurotransmitters are, but if you're not releasing anything, what would that baseline state be?

Loretta Breuning: Sure. I use neutrality as abstraction for what the goal is now, I know it doesn't sound like a goal to many people who've been indoctrinated to think we should be joyful in every moment. But neutrality is the fact that your brain is open to information about the world around you. Sometimes, there's bad information and I need to allow that in and say, "Whoa, I have to act fast on dealing with that." Sometimes there's good information and you say, "Whoa, I need to move toward that. This is something good for me that could meet my needs." So, we're receptive to the reality of the world around us when we're neutral, which means we haven't prejudged the information as either good for me or bad for me. That's what the chemicals are is basically a message of "Wow, this is good for me or wow, this is bad for me." Neutral is "I don't know, I'm open minded."

Melanie Avalon: Okay, awesome. I want to go over the actual chemicals. But just a follow-up question for that. So, the neutral open minded, there are people who identify as "Glass half full versus glass half empty." It just seems like some people seem to exist in a neutral state and yet they seem to be preconceived to have a negative perspective versus a positive perspective. But if there's anything coloring that does that mean you are releasing some chemical that's coloring that?

Loretta Breuning: When I think I know how to meet my needs, then I feel good. When I think I can't meet my needs, then I feel bad. How do I know whether I can or can't meet my needs? Well, in the state of nature, like for our distant ancestors, sometimes there was rain and fruit on the trees and fish in the pond and you could meet your needs and you had a nice tribe around you. Other times stuff went wrong and you couldn't meet your needs. That's why our brain is designed to respond to the physical reality of what's going on around you. However, then our brains wire from early experience.

So, when I was young, whatever met my needs built pathways to say, "Wow, this is good, this is going to meet your needs." Whatever caused me pain or obstacle to meeting my needs, it was built a pathway that said, "Oh, this is a threat, watch out for that." We're all going around with that wiring. But then in addition, in terms of the social needs, a good way to meet your social needs, a fast easy way is to be negative. A simple way of saying that is the old cliche that misery loves company, but there are other ways of looking at it.

One way is that "If I call up all my friends and tell them how bad my day is, they'll bond with me." Another way of looking at that is "If I talk to people and tell them our world is going hell in a handbasket, things are so awful and I spout them a long list of things I perceive as facts, then people will think I'm so intelligent and they'll want to be around me." These are just some examples of how being negative meets our need for social alliances.

Melanie Avalon: Gotcha. Yeah, I loved the whole section on cynicism and that lens. The reason I actually wanted to read that in particular is I have a friend who's very much like that and so I was very curious to learn what was going on there. Okay, so just as a foundation so that we can really explore this more, here is the, like, can you go over the four happy neurotransmitter chemicals that we have and just what their purpose is and how they actually feel in our bodies mentally?

Loretta Breuning: Okay, so dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin, and endorphin. Dopamine is this cliche about joy that we always hear that's the feeling of dopamine. It is a feeling of excitement, but its job in the state of nature is to let you know that you found a way to meet a need. The classic example is "If a monkey is hungry, it looks around, it sees fruit in the distance and dopamine turns on, it's like, wow, there it is, that can meet my needs and I can get it." If the monkey saw fruit that it couldn't possibly get, then it wouldn't get excited because that wouldn't be a good use of its survival energy to pursue that.

Dopamine is a good feeling that says "It's worth investing your survival energy in this because it will meet your needs." Now, we are never saying that to ourselves in conscious words, which is why some people get excited about buying a pack of cigarettes you know and other people get excited about gambling with borrowed money. All these unhelpful things that people do, you say, "Well, how could we possibly have a survival brain if people do these things?" The bottom line is because that thing triggered a surge of your dopamine in your past.

In the past, if you were having a bad day and you went out and shared a cigarette with a bunch of people on the balcony and they were your pals, it's like, "Wow, this really works." You know? Any time you have this feeling, especially when you're young, of like, "Wow, this really works." That build, that neurons connect. The next time you're like, "Ah, what can I do to fix my next step? What do I need to do, now?" You have that pathway and you see something similar to whatever triggered your dopamine in the past and you go for it. That's what we're all doing all the time. For example, even though I know this, I get so excited about writing my next book. And I really think "I don't really need to write another book because there are thousands of other things to do in the world, why do I really need to write another book?" But that's the only thing that excites me because that's the pathways that I've been building.

So, oxytocin is the iconic one that you hear about in all of this well-being news that gives you the impression that social bonding is the key to happiness. They make it look easy, like all you have to do is just don't work, just hang out with your friends and you'll be happy. But we all know that's not true, so why is that? They try to give us this impression, "Well, something has gone wrong with the world, but in the past, people lived in these tribes and they were happy all the time because they had a tribe."

But we see that when people have an opportunity to leave the tribe, they go for it. [laughs] So, it's got to be more complicated than that. In animals, we see that mammals live in herds and packs and troops and we're meant to think that this is this altruistic cooperative thing, mammals always cooperate and share, but in fact, animals can be quite nasty to each other and they run toward the herd when they're threatened by a predator. Oxytocin is the good feeling that you have protection from others. So, that's the bottom line. What we want is protection from others.

You don't say that to yourself with your conscious brain. But when you're in a group and you know the current classic expression as they got your back, when you trust people to be there for you, then that triggers your oxytocin. Now, if you have unrealistic expectations, like, if I say, "Oh, Melanie would lay down her life for me." Well, then you're not going to lay down your life for me. If I mess up my life and go to you and expect you to fix it, then I'm going to be disappointed. So, it's all about your expectations. Where do my expectations come from is from my past experience with oxytocin and neurons connect, and that's what built my present expectations.

The famous example of that is, Marcel Proust wrote this book called Remembrance of Things Past, and he talks about "Walking into a bakery, and he smells this cookie, and suddenly his whole childhood is activated." It depends on how protected did you feel in your childhood and what particular moments did you feel protected and what do you associate with those moments? Could be a food, could be an activity, could be a face. So, everyone can learn more about their own wiring to understand what triggers our oxytocin.

Melanie Avalon: You talked in the book about how "When we're raised whatever we experience while we're with our mother, we identify as safe." Is that correct? Is that related to oxytocin?

Loretta Breuning: I didn't say that exactly because my mother was unsafe, so I wouldn't have said that. But whatever we experienced during a moment when we felt safe, we connected to that. Okay, so for one person, it's a mother, another person, it's like a physical place. Another person, it's an activity. Another person is like, the whole group. Many people say to me, my mother was nice, like, whenever the relatives came over my mother would be in a good mood and not yell at me. So, then you associate it with, like, the whole gang being there. It's rather individual and that's why it's so useful to understand your own rather than thinking, oh, maybe I have a disorder.

Melanie Avalon: Was that the case with animals, though?

Loretta Breuning: Yes, but animals lives are a little more homogeneous because a smaller cortex is more wired genetically, whereas a bigger cortex is born unwired and wires itself from lived experience. This is all explained in the book. But one thing animals have in common, "They're born helpless. They can't meet their own survival needs, just like us." And then their mother feeds them, so they're going to have this positive connection. They have to get their own food in a short time. Their mother doesn't give them solid food, so they have to learn how to go out and get it. And they're more focused on smells. They quickly build a link between, like, the smell of their group and the smell of their mother and the positive feeling of safety.

Melanie Avalon: Second oxytocin follow-up question. This is something I've wondered for a long time and I've talked about it with my therapist and such. We talk about how oxytocin is released by touch and cuddling and things like that. I don't like being touched, I don't like hugs, I don't really like cuddling. Like, when I was born, I was immediately put into an ICU box. That's my theory for why I don't like that. So, can that have an effect?

Loretta Breuning: Wow. Yeah, yeah. So, everyone's early experience is very critical. It may even have been not only that you weren't hugged, but possibly when you were hugged, it felt uncomfortable or overwhelming because you went from nothing to you were still fragile and then here are these big hands. So, everyone's wired by the early experiences they don't consciously remember. But I would say that touch still feels good to you on some level, but at the same time, you have a negative association with it.

But if you could rewire the negative association, then you could enjoy the positive benefits because there is some primal natural positivity about touch. But again, it's very learned. Like, the example that I always emphasize is, "We're told that hugging is good." But you all know the experience, if you have to hug someone you don't like, someone you don't trust that doesn't feel a bit good. You can't meet your needs with just fake trust bonds. You have to actually trust that you are being protected, but you also need realistic expectations, because if I expect this total protection as if I were a child, like, "Oh, my boss is going to take care of me, they're going to do everything for me." And so then I mess up at work and my boss doesn't take care of me. That was an unrealistic expectation and I may feel betrayed, but my expectations were off-base.

Melanie Avalon: Again, you pointed out something that I was like, "Oh, that makes so much sense." The idea of temporary trust and how we can trust strangers for like, actually we'll trust a stranger like, "Hey, can you watch my bag while I go over here?" But you talk about how there's not this long-term concern about them betraying us. We have low expectations in that relationship, so we can trust them for temporary things, which is pretty cool.

Loretta Breuning: Yeah. I always use the example of telling your life story to a stranger on a plane, so then you don't have to worry, like, what are they going to do with this information? A more daily example is, if you go to a stadium with 10,000 people and you all love the same either sports team or musician, then that gives you that mammalian feeling of a herd, but you know that those people are not going to be there for you tomorrow. But what it does create is this huge moment of like, "Wow, we're all together in this." That moment is a big oxytocin surge and that builds a big neural pathway. The next time I feel bad or alone, isolated, I think I'm going to get tickets to that event. Now my brain has created a solution. By getting tickets to that event, I'm going to get this good feeling again. Of course, I'd be better off creating deeper relationships in my daily life and reciprocal trust with real human beings. But it's so easy to look for shortcuts.

Melanie Avalon: How about serotonin?

Loretta Breuning: So, this is complicated. Everyone hears about serotonin in the context of antidepressants. But when I read this monkey study, this is really what got me started in this whole thing. I mean, first, it was just a hobby of reading monkey studies. And then it blew my mind that first, it has been known for a century that animals have hierarchies in their social groups. But there was a study in the 1980s that when I raise my status in the hierarchy, I get a burst of serotonin. That's really why people are driving themselves crazy trying to raise their status because they get a little burst of serotonin.

Now, all of these chemicals that I've mentioned. After you get the little burst, they're gone in a few minutes, your body metabolizes them. That's why we keep trying to do these things over and over to get more of the chemical. That's why people are always looking for ways to put themselves in the one-up position.

Now, this sounds so contradictory to the whole peace and love model that we're being taught, that it seems hard to believe that animals are always competing in status hierarchies. But then I started watching nature videos and David Attenborough, in his older series, he explains this over and over. So, then I started researching and actually collecting old books because it was widely known and accepted that animals have these certain behaviors to avoid getting bitten by a stronger animal, but then to avoid having their food stolen, they have to be the stronger animal, like, "Where can I go where I'm a stronger monkey, so, I can get the banana?" This is the lens through which we look through the world because it makes us feel that pleasure of serotonin, which is not aggression, but it's calm confidence.

What triggers my serotonin, you guessed it is whatever triggered it in my early years. For one person, it's maybe they were in the school play and they got a big round of applause. For another person, like they kicked a goal in a soccer game or they recited in front of their grandmother and their parents were very impressed. Whatever triggered your sense of social confidence in the past wired you to seek more of that today.

Melanie Avalon: I have so many questions about serotonin, but just some initial ones right now, because you talk about serotonin being in multiple lifeforms, even like an amoeba. Is it the only one of the four that has that broad range of life forms that it exists in, like single-celled organisms?

Loretta Breuning: No, I think it either it hasn't been studied or it's not available. I haven't been able to search for it successfully. But I'll tell you, I actually started searching for plants. Plants have the same operating system in the sense that their behavior is controlled by release of chemicals. So, what is their behavior is very limited but an example would be "Do I grow toward the sun or do I grow away from the sun? One chemical makes me grow toward the sun when that meets a need and another chemical makes me grow away from the sun when that meets a need."

Melanie Avalon: That is really cool.

Loretta Breuning: Isn't it? That chemical is not the same as dopamine, but it's similar.

Melanie Avalon: That's interesting. Yeah. I've noticed that because I've started growing cucumbers and they grow up my windows, actually, I love looking at how they-- you know they like to grow towards, it looks like they're motivated [laughs] by something. So, that's very cool.

Loretta Breuning: Yes, fascinating. Also, you may have heard? I heard when I was young, "Birth control pills are made from a chemical and that chemical is harvested from sweet potatoes." And I was like "What?"Just an example.

Melanie Avalon: Wow, that is fascinating. This is something I've wondered for a really long time because we often hear about how large percent, I don't remember 70% or 80% of serotonin is in our gut. Does the serotonin in the gut, though-- does it actually reach the brain or is it local to the gut?

Loretta Breuning: It's local to the gut. It doesn't cross the blood-brain barrier. There're a lot of people with a lot of different opinions on this. But I always go back to what job does it do in animals. Always these chemicals have multiple jobs, but the multiple biological jobs are always related to a common survival need. So, for example, "If I need to get food and I need to be in the dominant position in order to get that food, and then I need to turn on my digestive system to digest the food." It makes sense that when my serotonin turns on in my brain, I have the confidence to grab that banana and my gut turns on the serotonin that says, "Okay, get ready, food is coming."

Melanie Avalon: Have they studied if there's a correlation between amounts of serotonin in the gut versus the brain? Like, can you have high in one and low in the other?

Loretta Breuning: I don't know. But two things about that one is "There are the vasovagal people." I'm not a big follower of that, but yes, I think they would be and they would even say frankly that the gut serotonin controls the brain serotonin. I think they might even say that. I'm not saying that, but I'm just telling you there're a lot of different points of view. But what I would say is a lot of this is learned much more than we realize.

One person always has a problem with their gut. Another person always has a problem with their foot. Another person always has a problem with their nose. If you go to their early experience, you'll see that early injuries were experienced there and it builds pathways for your weakness to express there, the natural human weakness to express there.

Melanie Avalon: I'm so excited to talk about this because literally I see it all the time. It's usually just like a very simple quote. It's like "This amount of serotonin is producing your gut." And then, so that means you're happy. Literally, it correlates it to the brain and I've always thought, is the serotonin in the gut the same as in the brain? So, that's interesting to think about.

Loretta Breuning: Well, I'll just give you a simple example. Like when I was a kid, there was a lot of conflict at mealtime, we'd sit there and my mother would yell at us, basically. Then I would have an association between eating and negativity and stress. If I sort of snuck off and ate something on my own, then my mother would get angry at me for that. She wanted to control my eating.

I left for college when I was 17 and then I was like ecstatic about the fact that I could control my own food choices. That was like a pleasure in my life and I'm not going to give that pleasure up for anybody. I am never going to put myself in a position where someone else controls my food choices. I'm happy about my whole eating life. I'm happy about it because it feels like, "Wow, every day I appreciate this." Now many other people are the opposite. like, "Ah, I don't want to eat alone. If I eat alone, I'm unhappy." Or like, "I can't enjoy this food because my grandmother didn't have enough to eat," or it's whatever thought patterns you've created around it.

Melanie Avalon: We're really similar. I had an experience because when I first started changing what I was eating, like, I went low carb and then paleo and doing intermittent fasting. My mom's initial response was she thought it was very disordered. I got a lot of anxiety around eating around her in particular and eating around people because of that judgment. And then I did feel very, like you very free to make my own choices, but it's still collared with an anxiety, I've realized from that. So, that is so, so, interesting. I have a lot more questions about the status and all of that, but maybe while we're just talking about the four transmitters. So, how about endorphins?

Loretta Breuning: Sure. Endorphin is chemically the same as morphine. That's where the word comes, endogenous morphine, which is opioid. Its job is to mask pain with a euphoric feeling. If an animal is attacked by a lion and has its flesh ripped open, it can still run because endorphin masks pain with a good feeling so that you can act to save your life. Its job is not to make you sit around on the couch and space out. Its job is to mask pain so that you can act to save your life. And then in a few minutes, the endorphin is over and you feel the pain because in order to protect your injuries you have to be aware that you're injured. Animals, either die in a few minutes with endorphin or they survive the attack and they heal. We are not designed to go out of our way to stimulate endorphins. It's only there for emergencies.

I put very little time on this one because we're not really meant to go out of our way to stimulate it. But I have to say a lot about it because people do go out of their way to stimulate it. What I think is very unhealthy, where I live in California is sort of a cult of exercising to the point of pain and then convincing yourself that it's the path to happiness and bringing more people into that cult. So, I don't think that's right. I think when you do exercise to the point of pain you get a rush of good feeling which distracts you from the negative thoughts that you have otherwise in your life.

So, the next time you have negative thoughts you think, "Oh, I could exercise to the point of pain and then I would not have these bad thoughts. Well, that's really unfortunate. If that's your only tool for relieving bad thoughts, then you're going to end up injuring your body, which is why so many people end up doing that. The real goal is to know how can I stimulate my dopamine, serotonin, and oxytocin in healthy ways rather than to rely on the endorphin strategy.

Melanie Avalon: Some endorphin questions. One, I loved the-- it was a major epiphany. You talk about how endorphins evolved for-- well, their purpose is to address physical pain not social pain or mental pain. Today, we have way less physical pain, but we have a lot of mental and social pain because endorphins only address the physical. You talk about how we think the world is a lot more painful now when really objectively it was way more painful in the past probably.

Loretta Breuning: Yes, exactly, exactly. You know you read these old stories and a person lays down at night and there're bugs crawling all over them and vermin are eating their food and if you go to the outhouse at night there might be a snake there and there were neighboring tribes that would steal your children and try to kidnap you and torture you. I mean, life was hard and that has been really lost. People are now being indoctrinated to believe that their lives are so terrible.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. Why do you think we idealize both the past and do we idealize the future? Why do we do that?

Loretta Breuning: Well, many people have apocalyptic idea about the future, the future is awful. So, there's this process going on of building social alliances. Everyone is trying to-- you know I said we want protection from others. If you could get more protection by getting more people into your social allianceand then if you could get more status by rising in that social alliance and becoming the leader of it, then that feels good. One way to do that is to say things that other people relate to. If you say, "Oh, our lives are so awful today." But follow me and I'm going to make you happy, that succeeds in many cases and that's why so many people are doing that.

Melanie Avalon: More questions about that. One really quick tangent question. Why does laughing release endorphins?

Loretta Breuning: Sure. Laughing activates deep inner muscles in your belly that we don't use that much, so you only get endorphin. It's sort of like, if I sit at my desk for an hour and then I get up and move, I just get a little bit of endorphin. It's not enough to feel high, I mean, a little more with laughing. But the bottom line is, you could always laugh again. That's a good way to get some endorphins rather than taking some kind of pain behavior, which unfortunately there are so many examples. I use a simple example in my books. I love hot tubs. So why does it feel good? I realize it's like actually pain when you first get into a hot tub and that's triggering endorphin. But after five minutes in the hot tub, now I've gotten used to it, now I don't feel it anymore, and the endorphin stops and now I'm back to the person I was five minutes ago thinking about blah, blah, blah, whatever my blah, blah, blah is. Now I could get more endorphins by turning up the water, making it even hotter, but that would be crazy stupid. It just helps you understand that this is not the path to happiness.

Melanie Avalon: So, you're saying with the muscles it's stimulating a very, very slight pain that's creating the endorphins with the laughing?

Loretta Breuning: Yeah, yeah, it's not exactly pain, but it's like exertion, let's just call it, and how to laugh more. I talk about that in the book. I'm not a big fan of fake laughing, so, I'm more focused on how can you get real laughing. I have three rules for doing that. One of them is don't suppress the laughter you already have. Many people suppress their laughs because of some imagined social pressure that makes you look bad.

Then the next thing is, "Put a priority on your own sense of humor." Because many people like if a friend says you want to go see this movie and then you think that movie is not funny at all, and you never have time to see the movies you think are funny because you're going along with other stuff. If I ask people to see my movie, they might not like it, blah, blah, blah. Just take time out to watch what you like, whether or not other people approve of it and give yourself that endorphin.

Finally, how do you find stuff that makes you laugh? It's actually not that easy. I say that I might have to look through a list of 50 movies to find one that really makes me laugh. If I look through that list on a day when I'm in a bad mood, I'm just going to end up feeling worse. On some day when I'm not feeling bad but I'm just too tired to do real work, I look through this list of 50 movies and I find "Oh, I'm going to love this one, I'm going to love this one." And then I put it aside and save it and then if I have a bad day, if I have dental work [laughs] and it's there and it's ready, and I'm like, "Oh, I'm so happy in this moment because I've wanted to watch that movie for months even though I'm having dental work."

Melanie Avalon: Is all this laughing stuff in the anxiety book? I don't think I've read this part of your work yet.

Loretta Breuning: Really? Okay, well, I have a blog post on Psychology Today, "Three ways to give yourself the gift of laughter" something like that.

Melanie Avalon: I'll have to read it and put it in the show notes as well.

Loretta Breuning: Yeah, I can't remember if it's in the anxiety book.

Melanie Avalon: So, actually, question about laughter. I've heard that humor and laughter is a way that we deal with, like, things that don't make sense in the world. It's like a way to deal with things. Is that true? What's the purpose of it?

Loretta Breuning: Yeah, I heard it's like, "Oh, this is it, here it is. Three ways to medicate yourself with laughter." Because you've heard that thing that laughter is the best medicine. Three ways to medicate yourself with laughter. That's the blog post that summarizes this.

Melanie Avalon: Awesome. So, I'll put links to that in the show notes.

Loretta Breuning: Yeah, on psychologytoday.com. I heard a theory that it's about social discomfort. If you hear someone is in this situation, like social yeah, the potential for social discomfort. If someone else is in a situation of social, "Oh it's the release of anxiety." So, someone else is in this bad situation and maybe I laugh with relief because, like, I'm imagining projecting myself into this situation. And then I'm sort of relieved that I'm not in it or I'm relieved when I hear a way of dealing with it or just, like, I'm so afraid to think about this. But then, when I hear another person being in that situation, then it gives me a little bit of relief because it helps me deal with my own fear of being in that situation.

Melanie Avalon: So do any animals laugh? If not, is it because they don't have that whole narrative in their head analyzing their social situations?

Loretta Breuning: A lot of this is a matter of definition because a currently popular fad is animals do a lot of play. If you're equating play with laughter, then they would say, yes. But I'm not a big believer in that. Yeah, they do have even videos where it looks like animal is laughing. So, here's a simple example. If you are a big monkey and I'm scared of you, then I will look at you with a wide grin and this is showing your teeth. That's not smiling or happiness at all. This is bearing your teeth to show I'm not afraid of you, look I'm strong too. A lot of these animal behaviors are misinterpreted.

The same thing with young mammals are very rough with each other. And we're told, "Oh, it's just play, it doesn't mean anything." But this play is building skills for social rivalry later on, where they constantly fight, really. In order to fight without getting killed, you need a real visceral physical awareness of your own strength, so that if I'm locked arms with you, I know, okay, I can win or I'm not going to win, I better pull back. So, my confidence and my strategic ability to navigate safely in the world around me full of threats. It's like, on the one hand it's bad, but on the other hand it's good if I feel confidence in my ability to navigate.

Melanie Avalon: Because you talk all throughout your books about all these misconceptions we have idealizing animal relationships and it's really fascinating, even something you talk about the role of-- when we think pets die of broken hearts, because yeah, what's happening with that?

Loretta Breuning: So, there are different stories. People may have heard a different story. But the main story and I have the book right here, this is like I said, The Inner Mammal Institute started as a book collection, because when I hear these things, I go and buy the book, so I have it. Now. Jane Goodall with all good intentions went to study chimpanzees and needed to habituate them to her so that they would tolerate her presence. Over time, she started doing that by giving them bananas. Now, bananas are in no way the natural food of monkeys, but it's like eating a candy bar to them. And with no effort so from the animal brains equations like, "Wow, I'm getting a huge reward with no effort, this is really worth tolerating that lady."

So, imagine what a revolution from all through millions of years of history, primates had to work hard for every bite of food they got, and then suddenly one little chimpanzee is born having bananas handed to him. So, that little chimpanzee did not learn natural survival behaviors. Once again, I have no critique of Jane Goodall whatsoever because the minute this was understood, she stopped doing it. She told other people to stop doing it. I'm not criticizing it, but I call it's the distinction between a pet and the natural state. Pets do not meet their survival needs. They rely on others to meet their survival needs. With humans, if you are living in your mom's basement and ordering pizzas on her credit card, then you're a pet. [laughter] So, then if your mother died, you would not be able to meet your survival needs. That's what happened to this first chimpanzee who was raised on bananas.

Melanie Avalon: Got you. Yeah. This is so, so, fascinating. Here's an overarching question about the four in general. It seems to me, like, I've always identified as a dopamine girl. I feel like I'm very dopamine driven. Two questions there, one is "Do people like one of those more than others usually, and if so, why?" The second question would be is dopamine-- because dopamine is the one that is the anticipation of getting something rather than getting something whereas serotonin, it sounds like, you have that feeling of status and safety, oxytocin, you have that feeling of trust, endorphins you are relieving pain. So, is dopamine the only one where it's the journey, not the actual experience?

Loretta Breuning: Good question. I know that there are other people giving information about this, so I'm not meaning to criticize or correct you, but I know that others have said this. First, I'll say that in modern psychology, there's this trend toward typologizing people. People have learned, "Take this survey, are you this type or that type?" This happens because people click on that and people get their Ph.D. dissertations by typologizing because it's a fast, easy way to quantify.

I believe that we all need all of these chemicals. I understand, I'm like you, I feel like I'm more of a dopamine person, but that doesn't necessarily mean I was born that way, but I learned from past experience that I built pathways of like "I can succeed turning on my dopamine and feeling good that way." But my pathways for turning on the other chemicals are not as well developed.

I think I would actually better off working on stimulating the other chemicals rather than just relying on the happy chemical that I already know. It would be like if I were a primitive hunter gatherer and I were already good at fishing, then should I put all my effort into getting more fish or will I better find some fruit? Because if I only live on fish then I'll lack fruit. But when I first try to stimulate the other chemicals, I'm not good at it. I would rather do something I'm good at, but I might better off spreading my effort.

Now, when you say is serotonin the feeling of like you already have it? Well, no, nobody ever feels like they already have it because our brain always habituates to what we already have and we look for the next thing to stimulate more. Whatever status you already have, you take it for granted and then you're like, "Oh, how can I get the next status?"

And with dopamine, it's anticipating. Yes. But if a person is in medical school and they're like, "Oh, only two more years to go and then I'm going to be a doctor." The serotonin is the anticipation of how I will feel socially confident when I'm a doctor and the dopamine is the joy of anticipating that a need will be met.

Melanie Avalon: Where does the innate sense of satisfaction regarding that actually lie? What I mean by that is, so like in my journey, identifying is the false idea of being a dopamine person, but I have a lot of goals and then I reach them and then they do feel really good. I understand that we habituate to it.

Loretta Breuning: You feel really good about it because you're a person who was able to do that.

Melanie Avalon: Able to accomplish the goal or able to have that view of it.

Loretta Breuning: Able to accomplish the goal.

Melanie Avalon: Okay, that's what I was wondering. I was wondering if is dopamine more, "Satisfying?" And that's why I'm like where does the satisfaction lie? But is it more satisfying if you do keep accomplishing the goals and you do feel like you can keep doing it? Is that the distinguishing factor?

Loretta Breuning: First, I would say that this idea of satisfaction is a product of a modern model of happiness, a Buddhist model of happiness, which says you should not keep striving, you should be happy with what you have. But this is not how the brain is designed to work. The brain is designed to motivate you to take that next step. A simple way to think about it is "If you are a primitive hunter-gatherer and you found a tree full of ripe fruit and you said, wow, this tree is so good, I'm just going to sit here forever and never move again." You would starve to death if you did that.

We are not designed to say, "Oh, I'm satisfied, I'm not going to do anymore." Now consciously, from the perspective of a college philosophy class, you'd say, "Oh, well, I should create the sense of satisfaction so that I don't have to keep doing this." Yes, I know that's the Buddhist view that is woven into all of modern psychology, but it's not physiology. The bridge between these two things, many people think, "Well, if you never have the feeling of satisfaction, then you'll just drive yourself crazy forever and ever." What you've pointed out is the middle point where you say, "Well, I don't have to keep doing that again because I already did it. Okay?

So, I'll give you a fascinating example. Christopher Columbus after years and years of effort and strain, so finally discovers this new world, goes back to Spain, and like, this is all I'm reading a biography of him. Now, this is all far riskier than you could even imagine. What does he do then? He goes back four times and finally it kills him. So, same with Captain Cook. He goes around the world, he discovers new continents, new islands everywhere. And what happens? He does it again and again and it finally kills him.

This is what people tend to do, is repeat whatever triggered their happy chemicals in the past. Bu the solution to that is not to do nothing and to sit on your butt and say "I should be satisfied with what I have." But to say "I'm tempted to repeat myself because I was already good at that." But what if I open my mind to the thousands of other possible ways to feel good?

Melanie Avalon: I'm so haunted by this question. I had Dr. Anna Lembke on the show for her book Dopamine Nation, and I was talking to her about this. I feel like I have, like, a work addiction, but it also feels very sustainable. Like, I just feel like I could just keep doing it and I'm very happy.

Loretta Breuning: Right. I totally agree with you. I totally agree with you. Most of these popular books, they come from academia where there's this shared paradigm, which is "Society is bad, all of your unhappiness is society's fault." And then the book pretends to be full of science, but it all fits the paradigm, the template of it's all society's fault. That's my next book is going to be about.

Melanie Avalon: I was so happy. I really appreciated reading-- It was in the positivity book, The Science of Positivity, this role of-- actually, it was in the Status book as well, but this idea that we blame society for all of these things we interpret as problems. Social status and things happening in the world. But you point out that these are all just evolutionarily natural things and so they manifest in society, but society is not creating them. So, like clothing, for example. Clothing or social media, what are practical examples of how we as humans manifest these social hierarchies and status and see it as a negative thing, but really maybe it was there all along and it's just manifesting as clothing and social media.

Loretta Breuning: Sure. The animal brain does not have abstract concepts. It's just in the moment. That means when I feel like I'm better than you because you used the clothing and what was the other example?

Melanie Avalon: Social media likes.

Loretta Breuning: So, anytime is like, I got more likes than you or my outfit is more in the latest fashion than your outfit. If we could imagine, like, hunter-gatherer stone age people and I collect this beautiful stone and find a way to drill a hole in it and put it around my neck, and then you find a better stone that looks even better in your opinion. You feel proud of, like, "Wow, I got it going on." That's the feeling we like and we do whatever is within our sphere to stimulate that feeling. And we can do it without putting other people down, that's the focus of The Status Games book. But we are subtly putting other people down, but we could focus on just the fact that I take pleasure in feeling proud of my accomplishment.

But the reason that happens is because I'm comparing myself to others and no one wants to admit that they're doing it, they blame society for doing it. But if you learn to notice, you are comparing yourself to others all the time, and the reason you do it is, animals do it every minute because they'd get killed by a stronger animal if they didn't. They learn to keep their distance from stronger individuals and not to grab for a banana near a stronger individual by constantly making social comparisons and that's what we're still doing.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. This is just really freeing because we don't judge our-- I think, well, maybe we do, but compared to, like, our desire for food or sex, we accept that as natural. But we judge this idea of social connections and status. It's just very freeing to know that's a very evolutionarily driven thing and it's for our survival. And so, it's completely natural. How does that drive actually compare to the drive for food and sex? Because you talk about the biggest survival threat to animal might actually be being kicked out of the herd. Is that correct?

Loretta Breuning: Yes. So let's talk about reproduction. This is a huge factor in all of this. Now I am not consciously trying to spread my genes. But in the state of nature, so many behaviors are all devoted focused on doing things that spread your genes and they've learned that the individuals who are higher in the social hierarchy get more mating opportunity and more of their offsprings survive. You could say that every single one of us is descended from individuals who got the one-up position because that's what it takes to keep your genes alive. And so, that's why you feel so good. It's not just being driven out of the herd, but if you're at the bottom of the herd and you get no mating opportunity or your offspring die, then your genes are wiped out. Although you don't consciously think, "Oh, I don't want my genes to be wiped out." The reality is that your mammal brain reacts to that as if you're about to die. The simple example of that is a bad hair day. If you look in the mirror and you think you lookd fat, I look fat, right? If I look fat, nobody's going to want to mate with me, nobody's going to want to be in my social alliance, and then my genes are going to be wiped out off the face of the earth. Nobody consciously thinks that. But if you watch David Attenborough's early nature series, it's over and over and over.

Melanie Avalon: There're so many modern things we do that are just fascinating to know what's actually behind that. Like, you talk about how the purpose of modern cocktail parties and how that's actually relieving. That's the way we're one-upping each other, like verbal spatting rather than physical fighting. Like, is that what's happening with cocktail parties?

Loretta Breuning: That's a very good thing because if you read history, people were at war, like, all the time. It's unbelievable. Isn't the war of words so much better than losing your son in some ridiculous battle?

Melanie Avalon: That is so interesting. Would the parallel in animals be the animals that fight or establish themselves with color, like peacocks?

Loretta Breuning: Oh, very good, very good. Yes, very good. So, I talk about that in, I think, The Science of Positivity, right? And peacocks, I never professed to be a bird expert, but the animal example I use in there is mandrill, which is a kind of monkey that looks like a baboon. When you study this monkey and I tell the story of how I came to know about this, which is this hilarious story, but the brighter their colors, this is the males, the more the females want to mate with them even to the point where all the females will go with the same guy who happens to have the brightest colors. Every species has some variation of this. Take a class on evolutionary biology or evolutionary psychology and you see a thousand variations on the same theme of everyone in this species knows what counts for status in that species and it never fails that that status marker also promotes biological survival of the young.

Melanie Avalon: That goes into a really-- talk about people being offended, but like a sensitive question, which would be, okay, so we like to-- I keep saying the word judge, but we think it's okay to be attracted to somebody for their intelligence or their sense of humor. But it seems shallow to be attracted to somebody for their physical appearances. Isn't it all just based on what will be the best reproductive match for you?

Loretta Breuning: Yes, but it's also not just the best, but the best that you can realistically get because if I think some certain-- I'm trying to think of a movie star I can't even think of, let's say Andrea Bocelli. [laughs]

Melanie Avalon: I love him. [laughs]

Loretta Breuning: [laughs] Let's say I think, "Oh, I can't be happy unless I mate with Andrea Bocelli. Well, then I'm not going to mate and my genes are going to be wiped off the face of the earth, so I better get realistic fast. And somebody calls it hilarious. It was called the Disney Theory, which is, "Does everyone have their own special prince or does everyone know, well, I really would rather be with the prince, but this is the best I can do." I can't remember how she looked at, but she said, yeah, the Disney Theory is not-- the Disney Theory is that "Whoever I'm able to get, I actually see him as a prince." And she said, no, that's not true.

Melanie Avalon: That's interesting. I interviewed Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, and he has a book called Don't Trust Your Gut and it's all about data. He talked a lot about the data on dating apps, how often people swipe left or swipe right. Basically, if you're super attractive, you're good to go. You can basically get a lot of likes or connections. But he talks about how if you are not that, it becomes a numbers game and you need to basically like-- if you make it a numbers game and if you look for other characteristics that you might find more attractive. I don't even know where I'm going with this. I'm just very interested and intrigued.

Loretta Breuning: Yeah, the great point is that "Everybody has the idea that it's not fair that someone else has a better life than me." Someone else is more attractive, they're having a good time, and I would be having a good time if I were more attractive. The better solution that I explain in my books I mean, it sounds a little like sour grapes, but do you think that really good-looking person on that app is really in their heart, having the best life and the most happiness? I don't think so, because we've all known people who-- it's sort of been a lot of movies about this. That if you could attract anyone that you never build the inner skills to appreciate others. You just think, "Oh, I can mistreat them and then someone else will come along. So, they don't build the pleasure of an enduring relationship that comes from mutual tolerance." So, we're all in the same boat. We all have dealt different cards, but we have to live in a world of trying to do our best with those cards.

Melanie Avalon: On top of that, though, I just feel like it's important because I just feel like it's really, really saturated in society that if you are attracted people that's somehow shallow. I just feel like that's not the case. Like it's not shallow. At least I don't think it's shallow. It just seems very evolutionarily driven.

Loretta Breuning: I know exactly what you're saying because I almost remember, like, I was probably about 20 years old or maybe unfortunately, maybe older probably like there's this inherent attraction to someone with the classic looks. Let's just take nose, okay? So, a person with the right nose, they didn't do anything to deserve it, doesn't necessarily mean they have superior character. But you're more attracted to a person with a good nose than a bad nose. So, then if you get that person with a good nose, does that mean you'll be happy forever? No, because then you'll move on to the next thing. These are just impulses, but then we still are left with the reality of life after these little things. I remember when I realize like I couldn't get that perfect idealized person that I was attracted to on the biological level. You look for other forms of attraction. But the biological kind of attraction was all built around reproduction historically. Let's remind ourselves that before 1960 there was no birth control, so nobody wanted to mate unless they could deal with the children and so that was the constraint reality.

Melanie Avalon: We have all of these morality clauses that we attach to these desires and status and everything. But then you talk about how people who, "Reject that." Now they get their status based on not having status or seemingly." So we can't really escape it in a way.

Loretta Breuning: Yes, exactly. Where I live, the status is about hating people with big cars and feeling superior to people and saying "Oh, all you people who are just running after consumerism." You know what? I have never met anyone who's running after consumerism. I only meet people who are hating the people who they presume are running after consumerism. They are getting their serotonin moment by having somebody to feel superior to because they can't admit to themselves that they really care about being superior, so they have to find this indirect way of doing it.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, so you just really can't escape it. This is what I was talking about with it's everywhere. Like it's just completely opened my eyes. I had a very concentrated experience where I was like "Oh, this is what she was talking about." Because you talk about the role and we've talked about this throughout the episode, but you've talked about the role of identifying threats and how that happens in our childhood and throughout adulthood and how that whole lens and releasing cortisol. I had an experience where actually, before that, can you talk more about the role of cortisol in identifying threats and how this is becoming more of a nuanced question than I anticipated?

I loved what you talked about with the role of cortisol, determining if we move towards or away from something, and also the role of adrenaline and how that affects it. Because we can have adrenaline and experience something and it's only good or bad, I guess, if we have cortisol along with it that was really complicated. What is the role of adrenaline and cortisol in identifying threats and animals and humans?

Loretta Breuning: Sure. I should say that this is exactly the book you haven't read yet. You're really going to like that. A few huge things, first, cortisol is the bad feeling that your survival is threatened. It feels really bad right now even though the threat may be abstract or distant. A simple natural example would be, "I'm a gazelle, I smell a predator." Now, gazelle's live in a world where there're predators all the time and if they could never go out unless the world was 100% safe, they would starve to death. They go out to the water hole and there are predators there. But then they see that certain signal, like, "Is the predator just there to drink or is he going to run after me?" They learn the difference from their own lived experience. When they see that certain indicator, that triggers their cortisol, okay, and that triggers that bad feeling and the bad feeling tells you to drop everything else and do something to get away from this threat whatever it is, do everything, focus only on that.

You could see what stress is, is something that's vaguely linked to something bad that happened in your past in your youth. You see it. You don't even know why, but you get this bad feeling and now you can't focus on anything else. You feel like your whole life has to be devoted to getting away from that and you may not even know what that is or that may be something not even especially good for you. Like if you've just finished your bottle of whiskey and you're afraid to live if you don't have a new bottle of whiskey. The interesting thing about cortisol is, first if neurons connect, so you're building these huge circuits whenever your cortisol is triggered, but also it lasts in your body longer than the happy chemicals.

During that time, your brain is looking for evidence. If you're a gazelle and you smell a predator before you run, you have to say, "Where is the predator? So I run in the right direction." That's the job of your big human cortex, is like, "I feel like something is wrong. Let me gather evidence of what's wrong." But your big human brain is very good at serving your inner mammals. Once you feel like something is wrong, you're good at collecting proof. "I think he hates me. Oh, look, here's the evidence. I knew you hated me." You know.

Melanie Avalon: How does adrenaline play into that?

Loretta Breuning: Oh, adrenaline, the simple answer is adrenaline lasts for a very short time, and cortisol lasts for a long time. Adrenaline is "If I'm in the bushes and I hear a noise, that's adrenaline. It's like, what was that?" That freezes me so that I stop and collect information. Is it something good or something bad? Like, maybe I hear a noise and my friends are surprising me with a birthday party. Adrenaline is that excitement of, like, something important is happening, but I'm not sure if it's good or bad and then cortisol is it's definitely bad and then the other chemicals are, it's good.

Melanie Avalon: When it does come to threats, does it feel better to relieve a threat or to find something good or find something that we want?

Loretta Breuning: Great point. Often they go together because the way they work in nature is the most common threat in nature is hunger. If I'm hungry, hunger is actually cortisol. If I didn't look for food until I was starving to death, I wouldn't have enough energy to actually run after a meal. So, I start feeling hungry in advance. I look around for food and I say, "Oh, look in the distance, I think that might be food." And then I walk toward it. For some reason, I'm like, "Oh no, that's not food." That bad feeling of "Oh no, that's not food." That means that's not going to meet my survival needs, now I'm still hungry, now I still need to find food. It's a bad feeling that stops me from wasting my energy on a hopeless cause and shifting my attention to look for as better opportunity.

I'm always scanning for good opportunities and what is going to relieve the threat? In today's world a typical example would be? You get home from work, you have a bad feeling because you're having bad thoughts. Like, maybe my boss is mad at me, maybe this other person is going to steal my work without credit. Maybe my loved one is cheating on me. Whatever your bad thoughts are, how can I stop the bad thoughts? Well, I could do something that really fixes the problem, like talk to my boss or my spouse, but that's hard to do. Having a glass of wine is another option. In past experience, a glass of wine relieved the bad feeling because it was hard to think about the problem, you stopped reactivating the circuit of my boss is mad at me, my spouse cheating on me because you're focused on where's the corkscrew, where's the glass? That's how the different systems overlap each other based on how you wired them from your own past experience.

Melanie Avalon: The example that brought up this whole topic for me was I realized just how much our brains are looking for threats and then the language part of the brain remembering that. We had a power outage at my apartment complex and the whole complex went out. I thought maybe a transformer blew. I was thinking maybe it was going to be out for days. I wasn't even aware of the concept of that, that was like a thing. I was talking to my mom and she's like, "Oh yeah, it could take days." And I was talking to a friend. He said that as well. In the end, it ended up just being a tree that fell on the power line, so they were able to fix it in a few hours. But for a brief moment, I was thinking, "Wow, I didn't know that transformers could blow and get rid of our power for days. I was like, "I need to worry about this all the time." This is something I need to worry about. I was thinking about and I was like, "There are a lot of things that could happen at any time and I'm not worrying about them." It's just because I was exposed to this concept and now I'm going to worry about it. I was like, "I'm not going to worry about it."

Loretta Breuning: Yes. That's the whole thing about how people bond around negativity, because all these people in your life they were trying to help you, but they were really activating more negatives.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. I was like there are a lot of things I could be worrying about, so I'm just not going to worry about a transformer blowing.

Loretta Breuning: When I tell you, I had a slightly different variation of this. People may have heard there was, like, a lot of rain in Northern California recently, so a tree fell down near my neighborhood and blocked the road. It didn't happen in the direction I was going, but I could see that in the other direction, traffic was at a standstill for a really long distance. And I thought, "Oh, I'm so smart because now I've seen this so when I come home from my errand, I'm going to take a different way home." Well, guess what? I completely forgot about it. I'm on my way home and like an idiot then I land in this terrible backup of just sitting there. Now I felt twice as bad because I could have avoided it and I messed up. And then I'm thinking, what if I'm getting Alzheimer's? Why do I forget things? And then I thought, you know what? "I'm just going to enjoy this. I'm going to put on audiobook that I like," I was really at a standstill and read my email and just enjoy this moment.

Melanie Avalon: It's really, really, fascinating to think about because if you think about it, there are a lot of really bad things that could happen and probably so many things that I have no idea about and you don't know about them until you learn about them, like with the transformer, or you thinking about the Alzheimer's from forgetting, from not going that route, but there's just some purpose for us right now.

Loretta Breuning: Exactly. That's the whole thing, animals don't have a big cortex, so they only worry about direct threats, whereas humans we can activate threats abstractly. People think what could happen bad next year? What could happen bad in the next 10 years? What could happen bad in 100 years? What could happen bad a mile from me? What could happen bad 10 miles from me? What could happen bad on the whole earth? You just open up your scope more broadly when your life is safe just so that you could find other threats because we've inherited a brain that's designed to look for threats, and so people don't realize that the cause of this is because they're actually more safe, and they have all this energy left over to look for threats.

Melanie Avalon: You really only have time to worry about these more existential threats if your immediate physical needs are met. I think about this a lot with the news. I don't even watch the news, but people will complain about the news and the world and how unsafe everything is, and the way I think about it. This also ties into the whole ethical thing that comes in about judging, because if people are suffering, we need to be suffering as well. But the people who complain about this all the time, I just want to ask them, really, though, in your life, are you experiencing all of this unsafety and terribleness? Because most people, I feel-- I don't make assumptions, but most people I feel like are living their lives and everything is okay relatively speaking.

Loretta Breuning: If they are okay, but they're not in the one-up position. In your mammal brain, once you've met all the other needs, then all your energy goes to that need of, "How can I be in the one-up position?" The fact that Jeff Bezos has more money than you, you could get upset about that because the rest of your life is so safe and all your needs are met that you could get upset about that because it really meets your needs if you then bond with other people who are upset about how much money Jeff Bezos has. Then they can create that upset that they actually feel it so it's as if to them that they were starving and having rats crawling over their bodies when they go to sleep.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. Was it your book? I don't know if it was your book or it might have been the other book I'm reading right now. It was a study and it was saying that "People would rather have less money if they have more than people around them than more money, but less than people around them."

Loretta Breuning: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah exactly. There's the other thing of, would you rather have 10% more if someone else got 20% more? No. But again, these studies are done by academics with preconceived beliefs about this and then they project their beliefs onto animals and construct laboratory studies that suggest that animals care this way, but they don't. Animals, when they're hungry, they'll go for the food near them rather than worrying about how much food the other guy got.

Melanie Avalon: Because you talked about the cortex and the development of the brain, and you talk in your book "The role of brain size and length of childhood." These are pathways when they're initially formed in the human brain. What is the role of-- Until age seven or eight what is the role of the initial myelination phase and how that affect us later on and the role of pruning? I have a question about pruning specifically, but what is happening with these experiences during that initial development phase?