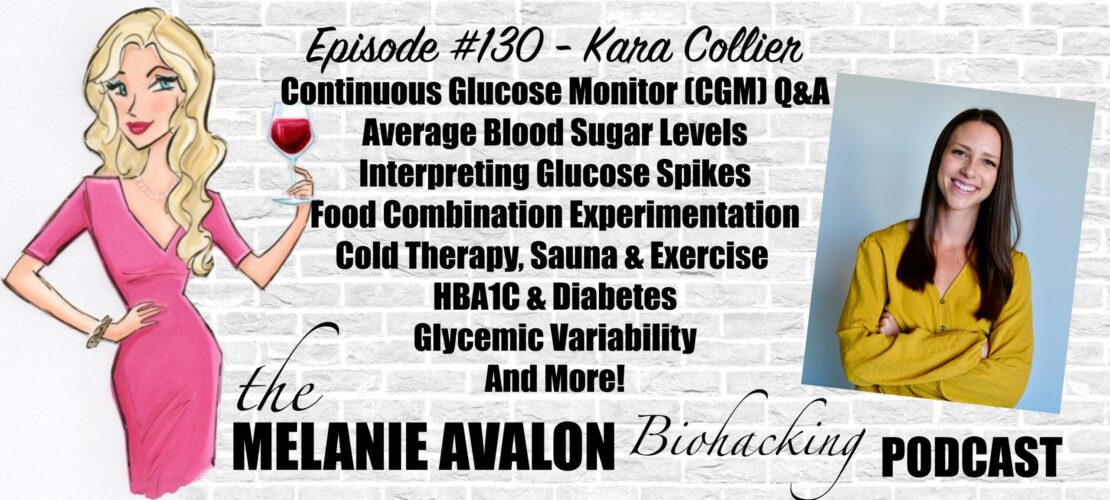

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #130 - Kara Collier

Kara Collier is a Registered Dietitian Nutritionist and Certified Nutrition Support Clinician with a background in clinical nutrition, nutrition technology, and entrepreneurship. After becoming frustrated with the traditional healthcare system, she helped start the company NutriSense where she is now the Director of Nutrition. Kara is the leading authority on the use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) technology, particularly in non-diabetics for the purposes of health optimization, disease prevention, and reversing metabolic dysfunction.

LEARN MORE AT:

nutrisense.io

SHOWNOTES

Go To Melanieavalon.com/nutrisenseCGM And Use Coupon Code MelanieAvalon For $40 Off!

1:45 - Lumen, Biosense & CGMs: Carbs, Fat, Ketones & Blood Sugar (Melanie Avalon): Join Melanie's Facebook Group If You're Interested In The Lumen Breath Analyzer, Which Tells Your Body If You're Burning Carbs Or Fat! You Can Learn More In Melanie's Episode With The Founder (The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #43 - Daniel Tal) And Get $50 Off A Lumen Device At MelanieAvalon.com/Lumen With The Code melanieavalon50

1:55 - IF Biohackers: Intermittent Fasting + Real Foods + Life: Join Melanie's Facebook Group For A Weekly Episode GIVEAWAY, And To Discuss And Learn About All Things Biohacking! All Conversations Welcome!

2:10 - Follow Melanie On Instagram To See The Latest Moments, Products, And #AllTheThings! @MelanieAvalon

2:35 - AvalonX Serrapeptase: Get Melanie’s Serrapeptase Supplement: A Proteolytic Enzyme Which May Help Clear Sinuses And Brain Fog, Reduce Allergies, Support A Healthy Inflammatory State, Enhance Wound Healing, Break Down Fatty Deposits And Amyloid Plaque, Supercharge Your Fast, And More!

AvalonX Supplements Are Free Of Toxic Fillers And Common Allergens (Including Wheat, Rice, Gluten, Dairy, Shellfish, Nuts, Soy, Eggs, And Yeast), Tested To Be Free Of Heavy Metals And Mold, And Triple Tested For Purity And Potency. Order At AvalonX.us, And Get On The Email List To Stay Up To Date With All The Special Offers And News About Melanie's New Supplements At melanieavalon.com/avalonx

4:20 - FOOD SENSE GUIDE: Get Melanie's App To Tackle Your Food Sensitivities! Food Sense Includes A Searchable Catalogue Of 300+ Foods, Revealing Their Gluten, FODMAP, Lectin, Histamine, Amine, Glutamate, Oxalate, Salicylate, Sulfite, And Thiol Status. Food Sense Also Includes Compound Overviews, Reactions To Look For, Lists Of Foods High And Low In Them, The Ability To Create Your Own Personal Lists, And More!

5:00 - BEAUTYCOUNTER: Non-Toxic Beauty Products Tested For Heavy Metals, Which Support Skin Health And Look Amazing! Shop At beautycounter.com/melanieavalon For Something Magical! For Exclusive Offers And Discounts, And More On The Science Of Skincare, Get On Melanie's Private Beautycounter Email List At melanieavalon.com/cleanbeauty! Find Your Perfect Beautycounter Products With Melanie's Quiz: melanieavalon.com/beautycounterquiz

Join Melanie's Facebook Group Clean Beauty And Safe Skincare With Melanie Avalon To Discuss And Learn About All The Things Clean Beauty, Beautycounter And Safe Skincare!

The Melanie Avalon Podcast Episode #70 - Kara Collier (Nutrisense)

9:35 - what is the most common question about CGMs?

10:30 - what is a continuous glucose monitor?

13:35 - why wear a CGM?

19:40 - HBA1C

20:45 - how long should you wear a CGM to find useful data?

22:25 - how much do we really know about glucose and longevity?

25:35 - DRY FARM WINES: Low Sugar, Low Alcohol, Toxin-Free, Mold-Free, Pesticide-Free, Hang-Over Free Natural Wine! Use The Link DryFarmWines.Com/Melanieavalon To Get A Bottle For A Penny!

28:35 - diagnostic criteria diabetes

32:25 - is it ok to spike over 200 Occasionally?

35:40 - changes in glucose

40:00 - standard deviation

40:55 - blood glucose and cryotherapy

44:00 - sauna & exercise

53:40 - being in a para-sympathetic state while eating

54:30 - experimentation

56:40 - SUNLIGHTEN: Get Up To $200 Off AND $99 Shipping (Regularly $598) With The Code MelanieAvalon At MelanieAvalon.Com/Sunlighten. Forward Your Proof Of Purchase To Podcast@MelanieAvalon.com, To Receive A Signed Copy Of What When Wine!

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #38 - Connie Zack

The Science Of Sauna: Heat Shock Proteins, Heart Health, Chronic Pain, Detox, Weight Loss, Immunity, Traditional Vs. Infrared, And More!

57:55 - food combinations

59:40 - why does alcohol lower blood sugar?

1:02:05 - stevia

1:03:15 - low carb eating and endogenous glucose production - adaptive glucose sparing

1:06:50 - is it harmful?

1:09:50 - restoring insulin sensitivity after being ketogenic

1:10:30 - CGM for gestational Diabetes or annual tests

1:11:20 - where can you place them?

1:13:35 - is there a Threshold of fat for CGM placement?

1:15:00 - accuracy

1:20:05 - consistency in readings

1:22:25 - does it hurt? is there another option?

Go To Melanieavalon.com/nutrisenseCGM And Use Coupon Code MelanieAvalon For $40 Off!

TRANSCRIPT

Melanie Avalon: Hi, friends, welcome back to the show. I am so incredibly excited about the conversation that I am about to have. It is with a topic that I know I have become obsessed with, I know so many of my listeners have become obsessed with, and I was thinking about this before we started recording just now, just how far we and people in the biohacking sphere, and companies have come in this whole sphere, which is the world of continuous glucose monitors also known as CGMs. I was thinking about the first time I ever heard about a CGM, I think it was an interview with David Sinclair on Rhonda Patrick. They were talking about wearing this thing on their arm that measured their blood sugar constantly and that just seems so unapproachable. At the time, I was like, "Oh, man, that's like next level" and now, here we are. I've worn one for a month. I don't have on one right now but I've worn one for a long time. So many of my listeners have as well. I have done an interview with NutriSense before. So, I will put a link in the show notes to that.

But I am here back again today with Kara Collier. She actually founded NutriSense, and now she is the director of Nutrition there. She's a registered Dietician, Nutritionist, and a Certified Nutrition Support Clinician. Her background is in clinical nutrition, nutrition technology, and entrepreneurship, which makes sense manifesting in the company of NutriSense. In the interest of time, because the purpose of today's episode is, I have received so many questions from listeners about CGMs, especially, since listeners have started wearing them themselves or they still have questions. So, today's episode is going to be a Q&A. So, what I will do is, I will refer listeners, I'll put a link in the show notes to the first conversation that we had because we really dived deep, deep, deep into continuous glucose monitors. So, that's a really nice background episode of listeners would like to listen to that. But today's episode is more rapid-fire Q&A style. Kara, thank you so much for being here, again.

Kara Collier: Yeah, absolutely. Happy to be back.

Melanie Avalon: I love Q&A episodes. I think they're so fun because we just get to go all over the place and see what the people are thinking. But actually, I wasn't anticipating asking this but I have a question for you. What is the most common question you get about CGMs?

Kara Collier: That is a good question. It probably depends a little bit on the audience, whether it's someone who's never heard of it versus someone who's using one, for the lay audience or maybe they see it on my arm, the most common question is, "Isn't that for diabetics or do you have diabetes?" So, that's the most common in that situation where someone who's using one and they're wanting to know more information. I think the most common questions probably come into, is this good or bad? What happens when my glucose spikes but comes down or stays elevated? The most common trend question I get is, "Why is my glucose doing XYZ while I'm sleeping those overnight sleeping values?" Because there's a mystery before a CGM. So, a lot of that's really novel information for people. I think just the nitty-gritty of the trends and what's happening with the data itself is quite a common question.

Melanie Avalon: For listeners to clarify, what is a continuous glucose monitor, just so everybody's on the same page?

Kara Collier: Sure. Yeah. So, technically, it is considered a medical device. It is a small, quarter sized device that you can put on the back of your arm. You put it on at home, you don't need any medical assistance to put it on, and I always describe it as an easy button. It comes in this applicator, and you push the button, and it's in the back of your arm. What's happening when you're pushing the button is it's putting this really tiny, flexible, painless microfilament just below the surface of the skin, and that microfilament actually allows the sensor to then put continuous glucose data onto your phone. So, if we wanted to know what our glucose was doing before this, we would have to prick our finger as probably many of your listeners are familiar with or you went to a doctor's office, got your lab drawn, and got a snapshot in time of your glucose. So, instead, a continuous glucose monitor is measuring glucose levels right below the surface of the skin every five to 15 minutes depending on which device you're using, and brings that to your phone.

Now, suddenly, we have this 24-hour graph of what's happening with our glucose. This device lasts for two weeks. So, for two weeks, you get this continuous data stream. If you want more than two weeks of data, you just peel it off like a band aid and put on another one and that's how they work. They are historically used for diabetics, which is why I get that question so often. If you see ads on TV for a CGM, it's usually geared towards a diabetic. In the US, it doesn't need a medical prescription as well. So, most likely if you're not a diabetic, you're going to have to convince your physician to write you a prescription. If you care about glucose for other reasons such as biohacking or just health optimization, and probably 99% of the time, they will not do that for you, unfortunately, which is part of the reason we started NutriSense. So, we want to remove that barrier to entry, so that everybody has meaningful data about their bodies. We really believe that in order to have optimal health and to improve health in this society, we need to have access to meaningful data. So, step one is making sure people have access and then step two is making sure it's digestible and actionable, which is where our software and service comes in.

Melanie Avalon: I'm so grateful to you guys for really, I mean, making this all accessible to listeners. I'm just thinking now what people say to me, because people will ask me a lot, because for listeners, you put a patch over it. So, since there's not just out there, most people do if they know what it is they, they think it's for diabetes. It's funny sometimes like, I've had conversations where people won't comment on it, and then at the end, I'm leaving, and they're like, "I hope everything goes well with your diabetes." I'm like, "Oh, no, I don't have diabetes," which I'm very grateful for. So, okay, you touched on actually a lot of things that a lot of listeners have questions about. So, first question, this comes from John. "Why wear CGM if you don't have high sugar levels?"

Kara Collier: That's a great question. I will try not to take a very long time to answer that question because there's many different reasons, different rabbit holes we could go down there. I think to take a step back, why measure glucose if you don't have diabetes? The first way to address that is, why is glucose important in the first place? Yes, high glucose levels are an indicator of diabetes and diabetes is an epidemic, especially, in this country. So, it's very important to make sure we're not headed towards that path. But glucose isn't just a marker of diabetes. It's so much more than that. I like to explain glucose as a vital sign because just like blood pressure or heart rate, our glucose fluctuates depending on what's happening in our environment. It's going to fluctuate either to appropriate levels or not appropriate levels depending on what we're eating, how much we're eating, what type of food we're eating, how often we're eating, but also our stress levels, our sleep levels, our physical activity, or lack of physical activity. So, all these core pillars of good health habits is going to then be reflected in our glucose levels. It gives us this insight into how we're just working as a metabolic being, so I describe a human body as having a metabolic engine, just like a car has an engine, us humans have a metabolic engine, and the fuel that helps this engine be powerful and run all of our systems is glucose primarily.

Whether you're eating carbohydrates or not, there's glucose in your bloodstream that is helping to fuel all the different processes that make us function optimally. We work best when glucose is in a physiologically normal range, and then we start to see all types of consequences if it's getting out of range. So, that's first step back of why glucose as a metric is important and then we have to think about well, what's the best way to understand our glucose levels if we understand now how important glucose is. As I mentioned, there's a few traditional metrics you could get hemoglobin A1c that has some flaws. It's not perfect test. We could go down that rabbit hole if you want. But it basically gives you an average glucose level. So, average is useful but it's not going to tell you how high it's going, how low it's going, how much swings are going on. Then the other blood value lab you could get is the fasting glucose level, which again is helpful. But it's telling us what's happening in the fasted state on that particular day and that snapshot of time. Our fasting glucose can fluctuate day to day and it's also not telling us anything about what's happening in the fed state.

Then our third option is the glucometers, our finger prick. This is your keto-Mojo, your contours, all of the different brands you can get over the counter on Amazon, and this is a step up, I think, because you can check it at random times. You can check it after you've eaten different days of the week to see what's going on but it still snapshots here and there. Now, let's say you check on your finger prick before a meal and two hours after and they're both 90 or 70, and you might think all is good to go but really you were spiking very high in between that but it's hard to capture with a finger prick. So, CGM is the first type of glucose monitoring that gives us that movie view rather than a snapshot. That movie allows you to know exactly how you're responding to meals, what's happening while you're sleeping, how your fasting glucose is trending from day to day, what those overall average values really are and your swings. So, it helps us to not cherry pick the data, miss things that we might be missing and really get a good idea of what's happening. Then, sorry, I just keep going [laughs]

To wrap that up is, then we start to see-- when we use this better metric, the CGM, we start to see things that we can't capture on these other metrics. I think that's the really big thing is, a lot of people are like, "Well, my A1c is normal. I don't need to wear a CGM." But a lot of people are having really high glucose spikes that aren't captured on the A1c, or they're having hypoglycemic dips, or they're having some sort of irregularity in their values that we just completely didn't capture in those other metrics. It's so much easier to capture those things early to see what I call yellow flags rather than red flags, because it takes decades to develop even pre-diabetes, and then more decades to get into diabetes. So, early warning signs are happening so long before. So, if we can catch them early and make small changes, maybe it's just your go to lunch meal is giving you a huge glucose spike. If you can swap that now before you end up in the pre-diabetes, diabetes range, then it's so much easier than when we have diabetes is not that we can't still address that and reverse that, but it's going to take a lot more work and a lot more time to then get back into that normal range. So, prevention, catching things early, I think is really just the way that we need to refocus our attention and that's what I try to get people to think more about, because it's not the traditional mindset about healthcare. Your listeners, I'm sure are more aware and more attuned to prevention and catching things early but it's so important.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, I will say wearing a CGM has honestly been-- I say this every time but one of the most eye-opening experiences, because especially, in the whole biohacking and health world, I feel like we try so many different things for health, mental, physical, so many different tools, and techniques, and tips, and supplements, and it can seem a little bit subjective in evaluating what it's actually doing if it's working. But with a continuous glucose monitor, you literally see how your body is responding to your dietary and lifestyle choices. So, it's just profound in my opinion. This wasn't even a question but a listener, Joan, she wrote in what her understanding was of HbA1c thing. So, maybe I could read this and you can let me know if this is like what's going on.

She said, "I've been reading a lot about them. My understanding is CGMs are better than the annual test. That's either a single test fasting or otherwise are more likely an HbA1c, which uses glycation of your hemoglobin to estimate what your average blood glucose is. It makes an assumption that your hemoglobin is of a certain size and that it lasts about 90 days. If yours lasts longer or shorter, that will make the result inaccurate. For instance, if you have anemia, it will be artificially low. Also, a healthy average could be hiding a lot of dangerous spikes. Once you wear the monitor, you know what your blood glucose actually is. So, you don't need a proxy measure like HbA1c. I will not worry about my result next time because I now know what my actually average blood glucose is and what spikes it." Is that a pretty accurate understanding?

Kara Collier: Yeah, I think she nailed it.

Melanie Avalon: Awesome. So, we have a question from Peggy. She wants to know, "How long do you have to use them to actually get useful data?"

Kara Collier: Great question. I would recommend at least a month is a minimum timeframe and I think there are a few different use cases. If you're fairly knowledgeable about health and nutrition, and maybe you're generally healthy, and you just want to see again, what are my true glucose values doing, what are some of my favorite meals, how am I responding to those, how is my basic routine affecting my health? I think a month is a great time to get that insight, understand the basics, and then maybe be able to take out a few key pieces of information. Where I would recommend at least three months if maybe you have a specific health condition that you really want to optimize. So, maybe you do have pre-diabetes, or PCOS, or you feel like you're getting hypoglycemic. Some more concrete goal that might take some time to experiment around, see some progress with, try a few different things, or maybe if you really don't know what to eat. Maybe you're just eating a general diet and you want to experiment with more of a ketogenic diet or maybe then you want to see what a higher carbohydrate diet does. If you want to take time to try a bunch of different dietary approaches, I would recommend three months for that. But it really depends on where are people at but each sensor lasts two weeks. So, I would recommend at least two sensors for most people.

Melanie Avalon: And I will say, especially, if you just get the two weeks, it's just so eye opening and it's like, "Oh. [laughs] You tend to want to go a little bit longer." Okay. I've got two questions and these go together. So, I'll read both of them. But they have to do with the data and the studies surrounding everything. So, Judith wants to know, "How much do we really know about glucose metabolism and longevity? What are the optimal readings? Do we know how to eat or not to eat to get them?" Then Stephanie wants to know, "What data or studies are used to establish what is considered a healthy rise and fall in glucose? Do we really know if these recommendations are optimal or are they just speculation? Could it actually be that low stable glucose is harmful long term? The studies behind everything, where's it coming from and what has led to the general recommendations that we have today?"

Kara Collier: Yeah, those are really great questions. I would say there are certain thresholds that we can feel very, very confident in of, these are goals of where we want to stay within and I can go through each of those because those were more set towards identifying what would be considered pre-diabetes and then diabetes. Then where I would say, it's definitely still gray is what would be optimal. So, we know what is normal and what would be considered non-diabetic versus pre-diabetic, and then there is less clarity around what is absolutely optimal for longevity. There's definitely research there, there's not nothing and we personally have had thousands of customers go through. So, we've analyzed our own data and categorized into people who are non-diabetic or diabetic to see what is at least happening in the real world. So, from there, we can get pretty good conclusions. But I don't think we can say with absolute certainty in order to optimize longevity, you must never go above this threshold. So, I can go through the nuances of the different trends to look for and what's super clear and what's less clear.

This is actually a great question, because I think there are a lot of voices in the space right now talking about glucose, talking about CGMs and unfortunately, I think there are some people talking about this with more certainty than there is and I think that that creates unnecessary potential fear or unnecessary potential restriction. Because some people are saying, well, maybe glucose should never go above hundred because there was one observational study about that. Now, everyone is eating nothing because they're scared of their glucose going high. I actually think that's really dangerous. I think it is a really good question. So, I will start the nuanced conversation and try not to be too long winded.

Yeah, so the first category we're really thinking about is fasting glucose and that's when you're fasted. So, technically being fasted from the research standpoint is at least eight hours without food. We have pretty good evidence that we want to keep that below 90, probably in the 70 to 90 range, although a lot of non-diabetics have glucose in the 60s, sometimes even lower and feel really great and we don't have evidence that that's a bad thing. Pre-diabetic would be when you're starting to go above that hundred threshold. So, we know for sure we don't want to see up above that too often. But there is a good amount of research there that below 90 is probably more optimal. I would say, I feel fairly confident with a body of research behind that one.

Then there's average glucose. This is what equates to a hemoglobin A1c as we mentioned, it's a proxy for your average glucose and we have fairly good evidence that we want to keep that below 105. So, 105 average glucose is equivalent to I believe 5.3% of an A1c, where technical pre-diabetes threshold is 5.7. So, I would say there's a little bit of a gray area where there's a pretty significant body of evidence that shows 5.7 to 5.3 is considered non-diabetic but it increases your risk. So, we might want to keep that more below 5.3% A1c, which again is equivalent to 105 milligrams per deciliter, which is what the actual average glucose would come out to. So, I would say both of those are fairly strong. A lot of evidence specifically pointing towards mortality, longevity, which of course are linked together and also insulin resistance and predictors of future diabetes. Then I would say, what has the least amount of clarity would be more in that postprandial window. Postprandial just means after a meal. This is all things related to when does your glucose spike, what happens after eating? We know from the diabetes research that there are two metrics that are very clearly defined from diabetes is that, any random glucose above 200 is independent diagnostic criteria for diabetes. So, if we're ever going above 200, that would be a big warning sign that's clearly established in the literature.

The other thing that is clearly established in the diabetes world is that, after a glucose challenge, so an oral glucose tolerance test where you chug a boatload of glucose and you see what happens to your body, you're basically stressing the system. If two hours after you've drank that glucose challenge, your glucose is above 140 and that is diagnostic criteria for diabetes. So, it doesn't give us a ton to work off. We know we don't want to go above 200 and we know two hours after a meal or challenge we want to be below 140. Then here there's a good amount of research for those postprandial more towards the lens of longevity and optimization. But I would say, again, I think this is the fuzziest area. If we're talking the strictest guidelines where I feel comfortable with how much research is out there, there is a handful of research showing that a peak glucose above 140.

So, not just two hours after a meal, but at any point in time and the day or night might start to increase your risk. So, there are some studies that show when glucose goes above 140, we see reduced insulin sensitivity, we see increased risk of diabetes down the road, some impaired beta cell function, higher levels of insulinemia that are usually associated with that. So, we're starting to see some increased risks. Then there's an even greater body of research that shows when we have spikes above 160. There's a lot more risk associated with that. So, I feel fairly confident that we pretty much never want to see our glucose above 160 and then we should try to aim to stay below 140 most of the time.

I like to remind people that our bodies aren't this-- most of the time actually, some people have very sensitive bodies. So, this is a generalization but we're not like a fragile microsystem where if we have one glucose spike to 145, everything breaks. It's a learning experience that you want to see that on the data, especially, if it's a go to meal. If you eat this meal every day and you're spiking a 150, that's a good moment to decide, "Okay, I don't want to be above 140 on a daily basis. If it happens every once in a while, and an event or a weekend thing, it's probably okay. But if it's going above 160, then we really want to dig in deeper of maybe if there is some underlying metabolic dysfunction going on insulin resistance, let's probe into this more."

Hopefully, that provides some clarity. There are definitely people that say when my glucose goes above 120 or even 110, I feel cruddy. I don't feel like myself, I have brain fog, and I think that's a very legitimate experience. I think we are all different. So, you also learn a better mind body connection when you're wearing the CGM, and you're compiling that against your subjective experience. So, if you feel best at a certain glucose range, do that. But if you're feeling the same at all levels, then I would aim for most of the time, stay below 140 and then if we're getting above that 160 range, we really need to dig a little deeper.

Melanie Avalon: I don't think I'd ever actually realized about those two proxies, the over 200 or the two hours later after eating above 140. I do intermittent fasting and then I do in my eating window either low carb or low fat. I don't really combine the two. But normally, when I do the high carb-low fat it normally spikes to the 130s, but 140s is usually the highest it ever goes. So, this is very, very eye opening for me. Stephanie, you actually-- you answered Stephanie's question. So, she said, "Is it safe to spike glucose over 200 when eating an occasional dessert?" It just interesting question that it's funny that she said 200. I'm not sure if she knew about this proxy, so, if it's like the random dessert.

Kara Collier: I would say it's safe in the sense that if it happens once like it's random, let's say, it's Christmas, it's like an annual thing or something and your glucose goes to 200, I would say it's safe as in our body has systems to clean that up. We have processes in place. When our glucose goes really high, that's going to cause some inflammation, some reactive oxygen species, but then we have all these counter mechanisms in place to help clean that up, get things back to normal. What's really dangerous, of course, is if you have a glucose spike to 200 daily, or even a couple times a week, or maybe even once a week, where the damage is starting to be more often than we can repair. That's when it gets very dangerous. But I would say, 200 is a warning sign that there might be some metabolic dysfunction going on.

Of course, I'm not a medical doctor. I'm not diagnosing here, but I would take that and do a little bit more research. Maybe ask if you can get an oral glucose tolerance test, get a fasting insulin level, see what else is going on, because even if we give the system that glucose challenge I was talking about 75 grams of pure glucose is what they use in an oral glucose tolerance test, it's a lot. That's a pretty good glucose load coming from pure, refined glucose. Even with that, we don't want to see it to go above 200. With a challenge to the system, in theory, we should be able to keep the glucose below a certain threshold and recover from that with a normal insulin response and insulin sensitivity. So, it's going above 200, I wouldn't say it's dangerous, but I would say it's a warning sign that there might be something more serious going on.

Melanie Avalon: Okay. I will say for me on the occasion that I've had a CGM on and done something that has caused a huge spike like that, it's a nice accountability partner. It's like, "Oh, okay. This is what happens when we do this." I really like what you said about the over certainty that some people have surrounding all of this because I do think just in general in the health sphere, that that's so dangerous because there's so much unknown about the body and so many different things work for different people. So, I get really nervous when people make very certain statements about things, especially, you were talking about the postprandial response to foods, and there's a huge debate, I think between a higher spike that drops faster compared to a lower spike that last longer that might have a higher area under the curve. So, I feel there's a lot of debate out there.

Kara Collier: Yeah. I would say, my most common answer on any podcast always starts with it depends. I know it's not fun, or exciting, or flashy to give all the nuance but I think it's really important because I don't want to unnecessarily scare people or people to reach for something that is not necessarily going to give more benefit than we know of. So, yeah, I think there's a lot of conflicting information and I hope to present the research that exists there and as much of an unbiased way as possible.

Melanie Avalon: You're definitely doing that. So, thank you. We have some more spike questions while we're talking about them because you were talking about spikes in relation to what they go up to so the maximum, but is there also any relevance to the actual change like the number of the spikes? So, for example, Didi says, she had heard ideally you want around a 30, what'd be the measure?

Kara Collier: Yes, she's probably talking about just delta that the changing glucose, I'm guessing like the shift. Yep.

Melanie Avalon: She thinks 30 would be ideal. So, if my CGM says, I'm 80 and then I start to go over 135, that's really not so great. So, is there a number for the actual amount in change or is it more just those maximums?

Kara Collier: Yeah, so the things that we look at for the postprandial the meal responses, we're looking at that peak like we talked about, we're looking at the delta, which she's referring to. It's how much your glucose has changed regardless of where it started, and then we're also looking at what's called the area under the curve. So, you could think of just how much exposure has your body had to glucose. All are important and all of them fall under that category that I would say is the most gray zone of, this is where there's the least amount of research of what we should be aiming for optimal health. There's a good amount of research again for diabetics and preventing diabetic complications but that's not exactly what we're looking for. What we do know is that glycemic variability, which is just your overall swings throughout the day, so not necessarily related to a meal, although most of the time when our glucose is swinging, it's because of something we ate, we know that those swings create more oxidative stress and damage than sustained high glucose levels, which is actually really fascinating.

There's a lot of research on this, where your glucose could be stable but in the 200s and you're seeing less inflammation and oxidative stress than if somebody has an average glucose of maybe 120 but they're spiking from 70 to 200 all day, up and down. So, we know that those swings are actually more damaging, which is part of the reason we don't want huge jumps in glucose. But the exact number, again, is a little bit more up for debate. What we have defined in our app, so, in our app, when you log a meal, you get a glucose score associated with the meal and it takes into account all the things I'm mentioning. So, it gives one score that accumulates all of these different factors and how we defined the threshold since there is a lack of research. Most of the research is observational, what happens when you put a CGM on a non-diabetic? What does their glucose normally do? That's what we did. We analyzed all of our data looked at specifically at people who do not have any insulin resistance and we saw 90% of people have a glucose delta of this, where this is more elevated and rare and we set our thresholds off of that because it's the best information we have right now.

We know that most people tend to have a delta or that jump in glucose less than 50 points but usually they're also less than 30. So, 30 to 50 seems to be pretty normal and this is similar to the observational data where you put a CGM monitor on a non-diabetic and see what happens, usually, they're jumping less than 30 points. So, I think that's a good general rule of thumb. But again, if we're looking at the nuance, I think it's important to take a step back, and instead of looking at that very granular moment of your glucose, look at what happened in 24 hours, how did that contribute to my glucose for the day. Let's say you had a jump, a glucose spike of 60 points but that was the only spike you had all day, and the rest of the day you're in the 70s, and your average glucose is 85, and you never spiked above 120. I would say that's a pretty darn good glucose day, whereas if you had to shift to 60, but you did that six times in the day because you were snacking throughout the day and your average glucose was 120, and your standard deviation, which is how we measure glycemic variability is 20, which we want below 14, then we might want to get those smaller and contribute to a better overall glucose day. So, I think it's important to take a step back to and see how that is reflecting overall in your day-to-day changes.

Melanie Avalon: Okay. That was really, really fascinating. The part about the high blood glucose compared to the swings to clarify about that, do those swings need to be high swings if a person is swinging but it's within the "healthy range" would that be different?

Kara Collier: Yep, exactly. It doesn't mean that it's best to have completely flat glucose line. So, a good question. When it's above normal levels of swing, So, again, we use standard deviation and this is pretty common in the literature too to measure glycemic variability. Anything below 20 is considered normal in the research world. But we have noticed that I think 90% of our non-diabetics never go above 14. So, we've set that as the optimal in our app, because it seems to be very common. I can send that study to you, too. It's quite interesting. But yeah, it doesn't mean that there's no fluctuation at all. It's that big glycemic variability that's more dangerous.

Melanie Avalon: You've touched on a lot of things that we have follow-up questions about. So, okay, this is something I've been dying to ask you and then another listener wrote in about it as well. So, I tend to do cryotherapy almost every day, do you do cryotherapy?

Kara Collier: When I get the opportunity when it's close to me. Look, as I mentioned, when we start traveling around, which does make things a little bit more difficult. But yeah.

Melanie Avalon: Have you worn a CGM in cryo?

Kara Collier: I haven't. But I have worked with customers who have.

Melanie Avalon: Okay. So, when I wear every time, when I wear it, it spikes so high. I'm like, "Is this real or is this the cold freaking it out?" But then what's interesting is it spikes pretty high and by high, so, I'll be like in the 80s and it'll go up to 140. But for the rest of the day, every time same pattern, it starts going down and then it goes down to below what it was before cryo, and then it stays low. Gina wrote in and she said, "I've seen the same spike that you've spoken about Melanie when doing whole body cryotherapy. Wondering if this is a real spike or just the effect of the cold on the sensor?" Do you know if it could be from the cold?

Kara Collier: Yeah, it's a great question. I would say most likely it is a fake spike so to speak and it's just an interference with the sensor during that because the sensor has temperature recommendations that are like normal temperature zones. I can't remember what the low threshold is but it's certainly not as low as the temperature that's probably going on. So, it's most likely an interference because we do know from research on cold therapy in general ice baths, all kinds of cold therapy that it actually lowers glucose and lowers insulin as well. So, that effect you're seeing of lowered glucose levels afterwards is most likely the true physiological changes that are going on. It's actually really interesting as you probably know that cold therapy stimulates our brown fat, which have lots of mitochondria. So, they are activated, they burn all this energy, and turn it into heat to help warm us up. And that burns through some of our glucose stores, which is what helps get those glucose levels lower and also lowers insulin levels with it. So, we do know that cold therapy of all type is going to have a glucose lowering effect and so, the spike is most likely a temporary interference while the therapy is going on.

Melanie Avalon: Because I've been wondering if it's that or if it's that the intense stressor makes my liver just dump all this glucose into the bloodstream and then it's going down.

Kara Collier: It's hard to say with certainty, but I don't see the spike when I see people doing ice baths where the sensor isn't in the water. They just see the decrease. So, that's why I'm hypothesizing it's most likely an interference since we don't see it in that situation.

Melanie Avalon: Okay, that's really interesting. Actually, and I was having a conversation with somebody the other day and they were like, "You should go in and wrap it up with something and try to keep it warm and see." I might do that and or I might try to time it with testing it with a glucometer.

Kara Collier: Yeah, I was going to say you could try pricking your finger and see if you can get that.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. So, this is a really good question. This is from Diane and she says, "Spikes that we see with sauna, exercise, or stressing the body, do these spikes affect hemoglobin A1c or insulin levels?"

Kara Collier: That is a really good question. The sauna spike is a little bit different than what's happening and maybe a spike from I just drank up soda or had a cookie. What's happening when we are in the hot therapy as opposed to the cold therapy is that, you will have a glucose spike and this actually isn't just an interference with the sensor. We actually see glucose rise in the research where people are checking blood values during the sauna. There's a couple of explanations for this. I feel like it's still maybe not completely understood but we do know it spikes. But a lot of this has to do with fluid distribution. So, if you think about just like osmosis, glucose in the blood is going to depend on fluid distribution. When we're really dehydrated, our blood glucose is elevated as well because there's not as much water in the bloodstream. So, that makes the concentration of glucose higher.

It's similar when we're having the sauna but it's also could be that factor of almost mimicking intense exercise. We also see a glucose spike during intense exercise. We are getting our heart rate up, our body's working a little harder and so we could see that glucose rise while we're in the sauna. What we know about the glucose spike during exercise is that it's a non-insulin mediated glucose spike. So, long story short, most of the time when glucose rises, insulin also follows to help bring that down. But we have some processes or situations where glucose could rise and insulin is not needed. There are different glucose transporters on the cells and some need insulin and some don't, and the cells and our muscles have different potential functions depending on what's going on. So, in the case of really intense exercise, you might have a glucose spike because your body really needs some energy right now, and the muscles can essentially soak that up without needing insulin.

What is theorized at least in the literature is that's a similar experience of what's going on in the sauna? I would say it's very safe to assume that it's not going to cause insulin resistance or hyperinsulinemia if you're doing sauna or HIIT therapy. These are actually very healthy behaviors that can improve our insulin sensitivity the rest of the day, lower glucose the rest of the day. So, very healthy habits that should not be of concern towards the detrimental effects we might think of with glucose. When it comes to contributing towards an elevated A1c, I would say that that's unlikely because most of the time what's happening when you go in the sauna, maybe your glucose spikes to 140. But it's usually up there for maybe 30 minutes max. I'm not sure what your experience is but most of the time when we're working with clients, it's a very short spike that comes back down when you're done. So, it's a very short amount of time that your glucose is higher, which when we're thinking about average glucose, then it's not really moving the needle to have that small spike.

Melanie Avalon: I'm just trying to remember because I tend to do a sauna session every single night. It's an infrared sauna. I don't recall seeing like a major spike for me personally but I wonder if it probably does raise a little bit.

Kara Collier: Yes, super interesting. I've seen it be really variable. Some people, it is a really large spike and for some people it seems a very minimal. I don't have an explanation for that. I have theories. My theories are that maybe if you do it really often you get used to it, where it's not-- just like if you do exercise often, you might not have as high of a glucose spike from high intensity exercise because you're more metabolically trained by a theory that maybe it's like that with a sauna. It's not as tough on the system so to speak if you're trained for it, you're used to it. But I'm not sure. But I do see variable responses. But a lot of people will have pretty high spikes. So, it's not uncommon if anyone's experiencing that.

Melanie Avalon: It just goes back to what we were saying about how we're all individual. So, you've answered April's question. She wants to know, how exercise affects glucose spikes. Then Joan, she says, "My reading suggests that exercise should reduce glucose but my experience is the opposite. Walking didn't affect either way but every time I got on my bike, my blood sugar would shoot up reaching around 140 within five minutes of beginning my ride and going over 160 eventually. It dropped down quickly again after I lock it up. I have a slice of pizza to see how I respond compared to a short ride and it was a bit shocking to see the two spikes exercise and carbohydrates are quite similar. So, my question is, why does my blood glucose rise with exercise. My theory is the liver releases glycogen to fuel the muscles but my muscles don't want it. I don't know how to test that." So, that ties into what you're saying with insulin mediated glucose uptake and I was going to ask if people are releasing this glucose while exercising but they have insulin, I'm not insinuating Joan has this, but I have heard there's a theory that insulin resistance starts at the muscle. If you're insulin resistant at the muscle, are they not going to uptake that glucose that's released from exercise? Is there a potential danger there or it's a little bit of a nuanced question? What are your thoughts on that?

Kara Collier: Yeah, that's an interesting question. I would say that is an abnormal response. I'll first say what we typically see with exercise and then try to hypothesize what might be going on in this particular situation. But most of the time with exercise, we could see two varying responses. One is with the lower steady state type of exercise. Maybe walking, jogging, light weightlifting, something of that sort, we typically see glucose either stay stable or decrease a little bit.

Melanie Avalon: Kind of like what she said.

Kara Collier: Yeah.

Melanie Avalon: She doesn't see much of a change.

Kara Collier: Yeah. The opposite, when something's really high intense--high intensity, so, doing sprints, maybe she's doing like a Tabata, I don't know exactly what she's doing on the bikes, maybe climbing or really heavy weightlifting, we typically see a glucose spike. You can think about these differences basically as supply and demand. So, if you are doing something low energy steady state exercise, then we have enough energy in the system to supply that demand. So, we stay at a steady state. We're using energy but we can also replenish it and fuel it at the pace it's going, where something more high intensity, suddenly you're demanding a huge amount of energy from the system and it doesn't have that demand right there. So, it creates some and that's exactly as she mentioned. Usually, this comes in the form of liver gluconeogenesis. So, your liver is creating some glucose really quickly in order to fuel that intense demand for energy.

Because our body would much rather create some extra glucose and have that temporary glucose spike, then not create enough and being an energy deficit and get hypoglycemic. Our body's working very hard not to do that. So, we tend to overshoot rather than undershoot as just physiological response. So, usually, we see that spike but again as I mentioned before it's different than a spike from if you're eating a candy bar or drinking a soda, and that your body is needing that energy. It's demanding it, and it's using it right away, and it's not necessarily insulin-mediated response. So, it's a healthy response is totally normal physiology. So, we wouldn't be surprised to see a spike. I'm not sure what she's doing on the bike, usually, like casual cycling, we wouldn't see a spike but if she's doing sprints or really high intensity, it might be normal to see that glucose spike.

Then afterwards, if you're eating a meal typically, if we've just worked out of any type, the steady state, the HIIT, the weightlifting, strength training, all of those things improve insulin sensitivity, they help improve fat oxidation, they help increase glycogen accumulation, all of these things that work towards better glucose control after a workout. So, usually, people see a lower glucose spike after a workout. If you're still seeing a glucose spike, an experiment I would prompt is to eat that same meal but without the exercise, and maybe it's even higher than the spike you're seeing right now after the workout. It's possible that it's blunting at some but it's still maybe just a meal you're not tolerating that well. Another thing that is just something I've actually learned through my experiences. I do a lot of intense hiking on the weekends. I might do a long hike, halfway through I stop and eat my lunch.

What I have noticed is that, if I don't let my heart rate get down low enough and get more into relaxed parasympathetic state before I start eating, I have a higher glucose response. This comes towards eating in that stress state. If your heart rate is going really high and you're eating, you don't digest as well, you don't metabolize as well, we're in this stress state. It's not a great time to be metabolizing food. One thing that just a tip to think about is making sure that you're giving yourself enough time to be out of that acutely stressful state before you're eating, and then also hydration. Like I mentioned, dehydration can contribute to elevated glucose levels. So, if you just worked out really intensely got super sweaty, maybe got a little dehydrated that can contribute to a higher glucose level afterward. So, just a couple of different things for her or others who have experienced that to consider.

Melanie Avalon: That's one of the reasons I think for me personally doing intermittent fasting and a one meal a day pattern works so well is because I don't eat until my work is all done. I eat in the evening and I'm always, I have my rituals surrounding it in a way. I'm in the parasympathetic state by the time I eat and I do think that that makes a huge difference.

Kara Collier: Yeah. I feel like a lot of people don't talk about that enough or underplay it as maybe not as hard science but it's so important. I've seen it all the time where people have their highest glucose spikes of the day at lunch while they're at work eating in front of their computer screen, while their boss is calling them, and they're trying to type at the same time, it's just like they're stressed. They eat that same meal on the weekend and it's perfectly fine. We see this all the time. It's really impactful.

Melanie Avalon: You actually touched on this. So, April was saying, "What experiments would you recommend doing once you have the monitor, eating before you exercise, eating after you exercise, opening your eating window with protein, carbs, or fat?" You touched on some of those then but you have some favorite experiments for people to run?

Kara Collier: Yeah, and that's where as you mentioned, if you just do the two weeks, it opens up all the ideas for experiments, but it's not enough time to do them all. There're so many things. Every time I put on a sensor and I've worn so many, I have like a new idea. I'm like, "Oh, I haven't tried that." It's like, "Oh, my gosh, how have I never tried that." But some of my favorite is, especially, if you're consuming carbohydrates, I know not everyone does, but if you are that's a great thing to experiment with is try different carbohydrates, swap them out. Eat the same meal but swap out a different fruit for another one or different starchy vegetable for another one to see which one is working best, and also, level of processing. Just a smoothie versus whole fruit, instant oats versus steel-cut oats, the different type of processing can make a big difference.

I would also say macro timing is really interesting. So, trying carbohydrates on their own versus protein first versus fat first, what kind of difference does that make time of the day if you're having a good high glucose spike at an evening meal, try that meal instead for lunch if you're eating that swapping those around, and then, as you mentioned with exercise. So, that's a big one. Especially if you're having a glucose spike to a food you like, that's what I think is important. If you're like, "I ate this chicken taco at a restaurant and I'm probably never going to eat chicken tacos normally and I had a big glucose spike, it's like whatever." If you're like, "I make chicken tacos every Friday and I had a glucose spike, that's a good moment to experiment." Maybe that's trying a different carbohydrate with it than you normally do swapping that, testing different portion sizes, having some protein beforehand, or the exercise. So, go do a workout before the meal, do one after, going to walk after, try different ways of seeing if you can mitigate that glucose spike. All of those I think are really good ones to start with that are just generalized.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, I will say my favorites out of the ones you just mentioned. I get a little bit obsessive with the difference in how carbs from fruit versus starches affect blood sugar. For me, I can eat all the fruit as long as it's just fruit. But if I add in just a little bit of a starch, it's shoots through the roof, which is really fascinating to me.

Kara Collier: It's so interesting. Yeah, and I have the most unusual glucose responses. I feel like because it doesn't match at all with glycemic index. But I have a lower response to white potatoes than sweet potatoes, a lower response to white rice than brown rice, just all these things that maybe are counterintuitive that I wouldn't know unless I had tried it. You start to realize which ones might work best, which ones can be the go-to's. So, yeah, swapping around all those different carbohydrates, I think is endlessly interesting.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, and the other one that you touched on that I love, I'm obsessed with the timing of-- the macronutrient timing. Before wearing a CGM, I intuitively felt that because my meal the ordering of it, and again, for listeners, this is just me, the point of all this is people need to get a CGM and see what happens with them. But for me, historically, before wearing a CGM, I've always eaten in a pattern where I start with wine, and then my meal is usually like high protein, and then if I'm doing high carb, low fat, then I end with the fruit. It's interesting for me because what I see on my CGM pretty consistently is the alcohol and we got a question about this that I'll read in a second. But the alcohol lowers it, the bulk of the meal, the protein lowers it and by it, I mean, my blood sugar, and then the fruit brings it back up and is the bump there.

Rose, for example, said, "Why does alcohol make my blood sugar drop so much? Seems like that wouldn't be the case." Do you play around with alcohol or do people see different responses with alcohol?

Kara Collier: Yeah, and we typically see again two varying responses depending on what type of alcohol. You can imagine that something like a sugary cocktail or more of a darker, heavier beer tends to have more of an immediate spike when you're drinking them because they're more carbohydrate rich. Or, sugary wine or like a sweeter dessert wine would have something type of similar effect where we see that glucose spike. Where most commonly we see that more dry wines and liquor in general without the sugary mixer to go with it tend to actually have that glucose lowering effect as you mentioned, so many people will notice a glucose dip sometimes hours after drinking, and this again could have a couple potential different reasons. But the one that is most commonly stated in the literature is that the body is prioritizing the metabolism of alcohol over metabolism of everything else. In the state of oxidative priority, alcohol is first in the system. So, it's breaking that down and it's not necessarily maintaining normal glucose production and homeostasis during that time.

Interestingly, we see such different thresholds for different people. Some people will notice that they have a higher fasting glucose the next morning after drinking just one glass of any alcohol. This might be due to that disruption in normal glucose production. But then a lot of people won't notice that effect that elevated fasting glucose unless they have two, or three, or maybe even four glasses of alcohol. So, everyone's seems to have a different threshold of how much might have a detrimental effect the next day. We definitely know from chronic alcohol consumption or excessive, so high amounts in one sitting that it does reduce that liver glycogen storage ability, impairs insulin sensitivity the next day, and could lead to higher glucose levels and higher glucose spikes the next day, but for a lot of people that effect isn't seen just from like one or two glasses.

Melanie Avalon: So, definitely an experiment for people to run.

Kara Collier: Yeah. Another fun one.

Melanie Avalon: I'm just thinking now, have you run any experiments on stevia?

Kara Collier: I have and I actually don't see any effect when I consume it. So, my glucose pretty much stays exactly the same but again, this is something where we actually see quite variable responses. I've certainly seen some people that have a glucose spike, usually pretty minimal, but still increased nonetheless from stevia, or even other artificial sweeteners, or sweeteners of any type. It's quite variable. Usually, it's either nothing or a small increase.

Melanie Avalon: The reason I was wondering about it was I recently was doing a deep dive on the literature on it and it's really fascinating. One study was talking about how it seems to have a beneficial effect on the pancreas and insulin production in the context of carbs. So, it helps if there's carbs around. Otherwise, it didn't have that effect. I know I'm being very casual on how I'm interpreting that study. But it was just basically, there seems to be a lot of nuances going on with it. So, I haven't had stevia in a while but now I'm wanting to wear CGM and do some experiments. Also, in the diet world, so, I think a lot of people, especially, on low-carb diets get a little bit surprised often with what they may find with CGMs. So, we have two questions about that.

Joan says, "I purchased a FreeStyle Libre and wore it for two weeks. I've been low carb for nearly two years. So, I was expecting very low glucose but instead, my averages were above 95. It's not disastrous but it must be all from gluconeogenesis or breakdown of triglycerides. So, I'm surprised it was that high. My normal meals did not elevate it at all, possibly dropping it a bit. So, I know there isn't much carbs in that." Then Stephanie said, "Can a high fat diet actually keep glucose elevated when the body is generating the glucose endogenously?" People on low-carb diets, is it possible that they can have high blood sugar levels despite not taking in the carbs?

Kara Collier: It is possible and we work with a lot of customers who have been following a ketogenic diet or very low-carbohydrate diet for a long time. So, we've seen this quite a bit and, in the literature, it's called either physiological insulin resistance or some people call it adaptive glucose sparing. First, it's important to differentiate that this is not the same as pathological insulin resistance, which is what is happening with diabetes. If we think about diabetes, our glucose is high and our insulin is high, which means we have a lot of energy that's not being utilized. Well, it's basically a disease of poor energy partitioning, like, we have all this energy but we're not using it well, it's not working. Whereas physiological insulin resistance, glucose might be on the higher side but insulin is low. So, it's more of what I would consider a DAP gene to the environment. Our bodies are so adaptable. We're incredible species, and if over time, the body is realizing that you're not giving it glucose exogenously. So, we're not eating carbohydrates, it doesn't need to do the same systems of therefore eating carbohydrates all the time. So, it adapts.

Usually, we start to see this at least in the clients we've worked with. We usually see this if you've been following a very low carbohydrate diet pretty strictly, so not deviating from it at all for usually at least a year is when we start to see this adaptation occur. Typically, what's happening is that, the body is now favoring ketones and fatty acids as their primary fuel source, mostly running off of that, specifically, the muscles. So, usually, muscles are our biggest sink for glucose. But when we're adapting, we're preferring these other fuel sources instead. But the body needs to still make sure it's making enough glucose, especially, if it's not getting any from the diet because some parts of the body specifically the brain and other systems are glucose dependent. They really can only run off of glucose. So, what happens or what is theorized, what we've seen working with customers is that fasting glucose starts to rise over time. That average glucose level is just a little bit higher than maybe in somebody who's not following a long-term ketogenic diet. But if you were to check fasting insulin, it would be super low.

It's not unusual for us to see people whose glucose is resting in the 90s, low hundreds, sometimes even 110 in this situation, but their glucose is never fluctuating because they're not eating carbohydrates, so their swings are essentially zero and their average glucose is usually the same as their fasting glucose, so, in the 90s or low hundreds. Then of course, the follow-up question I always get is, "Well, is this a bad thing? Is there any harm to this adaptation?" I don't think that we know the answer to this. I would hypothesize. No, it's probably not anything to be too worried about, especially, if you've checked insulin and it's low, I would recommend if your glucose is creeping up over time on a low-carbohydrate diet, just make sure just get a fasting insulin level double check and then if your average glucose is starting to go above that 105 threshold like we talked about, then maybe it would be a little concerning because it could be just some high levels of glycation happening throughout the body if we have a high average 24/7. But if your average is 95, never really swinging, I don't really see that to be any potential issue but we don't have a clear answer to that.

One thing I will caveat with is that this is documented in women who are following a ketogenic diet, who then do that oral glucose tolerance tests when they're pregnant. So, this is required at this point in time when you're pregnant and this how this adaptation was first identified were that these women were failing the OGTT is getting labeled as diabetic, but really they weren't. They were in this physiological state. We know from studying these women that, if they start to incorporate carbohydrates back into their diet and usually it's about three days of eating at least 150 grams of carbohydrates, this phenomenon goes away, and the adaptation changes, and they have a normal oral glucose tolerance test result. So, it's not the same as diabetes, where three days of change doesn't make you suddenly have normal glucose levels. So, it's more of an adaptation than a pathological state.

That's what I think is important to differentiate. I don't necessarily think it's a bad thing as long as your average glucose is still below 105. What I would be careful with though is if you're following a ketogenic diet, but then every once in a while, you have a big carb meal, maybe every other weekend, you go out and you eat 400 grams of carbohydrates, which happens all the time, we see this all the time with our ketogenic members, and then they have glucose spikes to the 300s, 400s because their body's in the state of physiological insulin resistance and that is not desirable. That is definitely going to have an effect on the body, and it's going to take a while for that to recover, it's going to be a lot of inflammation. So, if you're somebody who wants to incorporate carbohydrates here and there, we would work with them on maybe some more like metabolic flexibility, so that you have a good system to tolerate both carbs and fat as fuel and switch back and forth. But if you're like, "I love being keto and I don't really miss carbs. I don't need to have these big carb blowout meals," then I don't really see an issue with it.

Melanie Avalon: I'm so curious to know because when I was low carb for a long time, I definitely had higher resting fasting blood sugars but I wasn't wearing a CGM. This is years ago. I would love to know after meals if it was sort of that higher resting flatline or if it was spiking. So, you answered this question. Stephanie wanted to know, "How long does it take to restore insulin sensitivity after long-term, two to three years of ketogenic macros?" It sounds like it can happen faster than like it's not going to take years.

Kara Collier: No, we usually see it happen pretty quickly of just reincorporating carbohydrates, usually you're going to have some dysregulated glucose values for those couple days. If you want to ease into it, we can titrate carbs in and they'll take a little bit longer. It also helps if people are making sure to engage in physical activity, specifically, strength training that helps with that insulin sensitivity and easing back in.

Melanie Avalon: Then two questions that relate to what you just talked about with the diabetes test for gestational diabetes. Calamay says, "Why aren't they recognized for testing sugars in lieu of the gestational diabetes test during pregnancy?" Then similar question, Jessica wants to know, "Are there any studies and progress using CGM two or four times a week to replace or enhance glucose testing during annual physicals?" So, do you think there's a future for this of using CGM for these testings?

Kara Collier: I have a feeling eventually. The real question is how long will it take? But I have a feeling eventually that it will probably be optional of somebody could opt out of the OGTT and wear a CGM instead. I know some naturopaths that are already doing this, even though, it's not technical role. At this point in time, I think what will happen is to just slow to get there. There's research that's already been done that is using CGMs in pregnant women kind of comparing it. So, there are some out there and I'm sure there's more research being done. But it's a little slow to make those regulatory changes. I would say that the biggest barrier if I had to just hypothesize is that, it's easier for a physician to get a test result back and say normal, not normal than to analyze two weeks of their CGM data. It's more to put on the physician. I think we would have to do something where the CGM would spit out some type of diagnostic yes or no.

Melanie Avalon: Yes or no. [laughs] Yeah, like the outlet program.

Kara Collier: Yeah. I think if you have a little bit of a different physician you're working with that maybe is more concierge, or maybe gets to spend more time with their clients, or they're more knowledgeable in this space. They're probably open to it or would be in the future, but I don't know how long it'll take until it's mainstream.

Melanie Avalon: We have some practical questions about just actually using them. Zoey wants to know, "Do they have to go on your arm or can they be placed in a more discreet area?" Candace, similar question. She says, "I don't have one. So, I would be curious if you can put the sensor anywhere else on the body, so no one can see that you are wearing it." Catherine said, "I wondered the same thing."

Kara Collier: Yeah. So, there are two major companies making these devices. One is Abbott, who makes the FreeStyle Libre, and then the other is Dexcom. The Dexcom devices are approved for both the back of the arm and the abdomen. So, those are two approved locations where the FreeStyle Libre which is the device we use at this point in time is only approved for the back of the arm. It's the only location that has been clinically studied with the device to say, "Yes, this is working. Yes, this is FDA approved to be within the accuracy guidelines we recommend." So, by official rules, if you're using the Libre only the back of the arm, however, we have had people who don't follow those rules and still put it on their abdomen or other places. I would say nine times out of 10, it ends up perfectly normal. I have seen a handful of people who try it in other places and the data just looks funky. So, it would be off label use for the Libre.

Melanie Avalon: Okay. Actually, speaking to that Bridgid says, "Is there a threshold of fat that is necessary for accurate CGM measurement? I don't have a lot of fat in my arms. Could this be why my CGM readings never seem to match my finger pricks regardless of the 15-minute delay," which I'm glad she pointed out the delay.

Kara Collier: There isn't an official threshold that I'm aware of, but I know that this is an issue because the type one community, type 1 diabetes is typically not lifestyle related and it usually occurs in children. When you're younger, you get diagnosed. So, small children with type 1 diabetes tend to be very small and not have a lot of body fat on them. They do have issues sometimes with the sensor. This is anecdotally documented. So, it can be a conflicting variable but luckily at least in our app, we allow a manual calibration. As we were talking about just the logistics the way the sensor works, there's that little tiny flexible microfilament that goes just below the surface of the skin, and it goes into your interstitial fluid, and if it's not completely bathed in fluid, then it can be further off from a true value. So, you might have to calibrate more if you don't have as much fat on your arm and it can interfere with the placement a little bit. So, it's not that it's not usable but it can cause a bigger discrepancy in readings.

Melanie Avalon: We did get questions about the accuracy. So, a few of that-- all kind of go together. So, maybe you can address them. Meredith wanted to know, "Are they inaccurate when reporting low blood sugars?" And I'll tag on to that to ask you if they're more or less accurate at high or low sugar levels. Melissa said, "So, CGMs monitor interstitial fluid like you were just saying, not blood glucose. I've heard on your podcast and in conversations with Dave Asprey that there can be a 20-point difference in either direction, but it's the trends we're looking for. So, are CGMs really worth it. I've used CGMs for about a year now and I'm really good at understanding what foods and behaviors lead to what trends. But my numbers are more accurate with finger pricks. I guess, I'm just wondering what else is there to glean from a CGM after a certain point." Didi said, "I've heard that CGMs aren't necessarily accurate but are precise is my understanding. How do blood pricks compare? I feel like with finger pricks, I have more variability in numbers than my CGM shows. Is this just perceived due to poor data collection, so, the accuracy of them?"

Kara Collier: Yeah, the accuracy is a great question. For all CGM devices, whether it's the Libre or the Dexcom, they're all FDA approved to be able to be used in the diabetic community for making medical decisions for being to use and adjunct to insulin dosing. So, the regulatory authorities have approved that the accuracy is good enough for these purposes. But it is not necessarily perfectly accurate nonetheless. Essentially, what the FDA rule says is that, the values must be within 15% of true results. The gold standard of an actual accurate level would be a blood test. So, you go to the lab and you get a fasting glucose level. I'll talk a little bit about the finger prick accuracy in a second, but that's not the gold standard. When people are comparing the finger prick to CGM, neither of them are that perfectly accurate. Sometimes, you're chasing a unicorn is what I call it, but I'll get to that in a second.

They had to be within 15%, 95% of the time, and then within 20%, 99% of the time. Most of the time, they're going to be within that 15% wiggle room, which 15% can be a lot. So, I completely understand how that can be confusing. Essentially, what it is saying is that, while let's say, I'm on a fasting glucose, fasted state, and I just went to the lab and got my glucose and it was 80, and my CGM is reading 95 that would be within 15%, and we actually allow a manual calibration in our app, which none of the other apps besides Dexcom allows for, and that can lower that value to match more closely to an accurate standard. But just like one of your listeners mentioned, there's difference between accuracy and the absolute value versus precision. So, the devices are actually shown to be very precise usually within 2% to 3%, meaning that it might be 15 points higher, but it's consistently 15 points higher, which is why is really helpful about trends.

Again, let's say that your glucose jumps 80 points in a meal and takes four hours to come back down to normal, whether that baseline is 15 points higher or lower than true value, that's a trend that is really interesting. Same with maybe you start incorporating a walk after your meals and you see your average glucose drop 20 points, whether it's actually dropped from 100 to 80 or 110 to 90, it's 20-point drop nonetheless. So, those are the trends we really want to pay attention to. But if you do have a recent lab value to compare to you can calibrate that in our app. What I will say about the finger pricks is they fall under that same FDA rule of accuracy recommendation. So, some devices tend to be a little bit more accurate than others. It definitely varies brand to brand of just quality of the accuracy. But the finger prick glucometer devices aren't the gold standard.

So, let's say you check with a glucometer and it's 15% off but on a higher and the CGM is 15% off on a lower, and then you check your glucometer again in five minutes and then it's 15% in a different direction, that can be very confusing. Because you're seeing a different trend on your glucometer than your CGM. The CGM is very good for precision. So, I always recommend just adjusting the absolute value and not adjusting the CGM calibration every five minutes because the glucometer could be more all over the place. I have even been in the situation where I check at the same exact moment in time one hand versus the other and they're 20 points different with a glucometer. So, it's not a gold standard. So, I think that can confuse people because they're used to using their glucometer and it's a good proxy again, but it's not the gold standard. So, we don't want to use that as our truth.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah. The thing I found most helpful for me because now I've worn so many. I pretty much I can get a sense if one of the sensors is off and I've wondered more because I was talking with somebody else in the CGM sphere this week about it. I used to think, "Oh, the CGM itself is off but maybe it's the placement of it that made it be off more than the actual CGM." But the calibration really, really helps for my own calibration of it. I like to do it at a consistent time when I know my blood sugar level historically tends to be pretty much the same, which is in the evening right before I'm having dinner, so not in the middle of the day when it's swinging from stress swings and different things, I found that pretty helpful for me.

Kara Collier: Yeah. I would definitely recommend doing it when it's stable just because it's easier related to the delay that you mentioned. The CGM is measuring that interstitial fluid and I compared blood glucose to interstitial fluid like a train. So, blood glucose is at the front of the train and where interstitial fluid is like a car at the back of the train. So, that's level ground. They're at the same value. They're moving at same speed. But if you go over a hill, the blood glucose goes up first followed by that back train a little bit later. So, there's a delay when our glucose is fluctuating in the CGM. Usually on average in the research it says, 15 to 30-minute delay depending on the speed of which your glucose is changing. But when it's stable, it should be about the same as blood values. It's in better time to calibrate and compare.

Melanie Avalon: I think for listeners, if they haven't used one before, that might seem a little bit intense that it can be "off by that amount." But what you understand once you wear it is you get this huge overall picture with the calibration aspect to it. It's not as intense as it might seem, I think, for most people and the potential for it to be misleading at least.

Kara Collier: Yeah, absolutely. We do offer dietician support with our app. You get a one-on-one dietician. If anyone's confused on how to calibrate or what it means they're really helpful explaining that and helping guide the trends and how to adjust it if needed.

Melanie Avalon: One last question because I think a lot of people are probably really wanting to get one but they might have this fear. Shannon says, "I'm just simply scared of them. Something in my arm freaks me out. Is there another way? I'm scared, it will hurt that a needle is in my arm. What if I bump it by accident? Needles are something I've had to get better at. But things like IVs and a CGM make me have a lot of anxiety."

Kara Collier: That's a great question and I'm sure you can share your anecdotal experience as well as putting them on but they truly are painless. If you've ever pricked your finger with a glucometer, that is way worse. Yeah, way, way worse. [giggles] So, it's not like getting an IV. It's not like getting bloodwork done. The needle is only there for insertion. So, it just places that really flexible microfilament under the skin and then you don't have a needle in there the whole time, which is why for the two weeks when the sensor is on, you really don't feel it. You sleep with it on, you shower with it on, you work out with it on, and most people don't notice it at all. So, it's not like there's this harsh needle stuck under your skin for two weeks. It's not like that at all and it really is painless, but nobody ever believes me. So, bias.