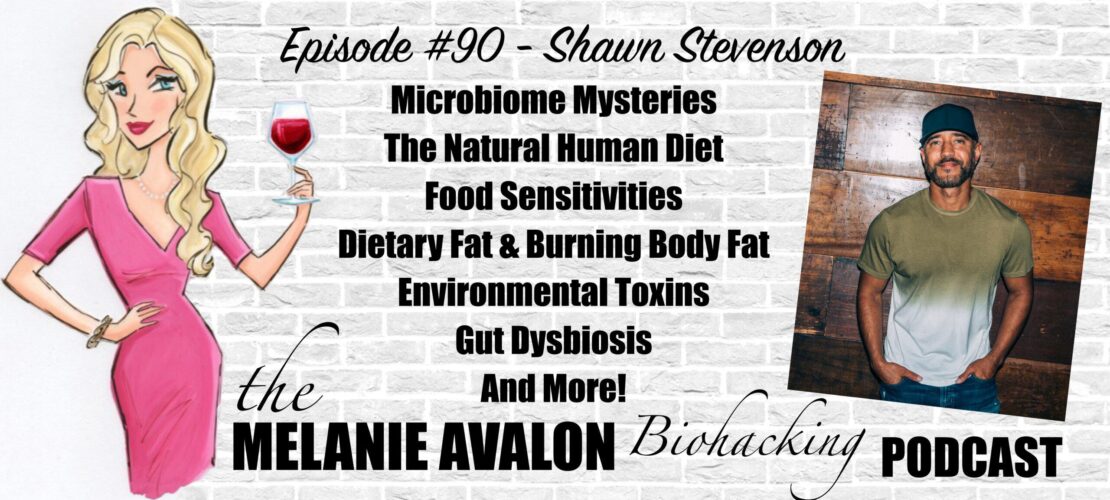

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #90 - Shawn Stevenson

Shawn Stevenson is the author of the international bestselling book Sleep Smarter and creator of The Model Health Show, featured as the number #1 health podcast in the U.S. with millions of listener downloads each year. A graduate of the University of Missouri–St. Louis, Shawn studied business, biology, and nutritional science, and went on to be the founder of Advanced Integrative Health Alliance, a company that provides wellness services for individuals and organizations worldwide. Shawn has been featured in Forbes, Fast Company, The New York Times, Muscle & Fitness, ABC News, ESPN, and many other major media outlets. To learn more about Shawn visit themodelhealthshow.com

LEARN MORE AT:

https://eatsmarterbook.com

https://themodelhealthshow.com

IG - Shawnmodel

SHOWNOTES

1:45 - IF Biohackers: Intermittent Fasting + Real Foods + Life: Join Melanie's Facebook Group For A Weekly Episode GIVEAWAY, And To Discuss And Learn About All Things Biohacking! All Conversations Welcome!

2:10 - FOOD SENSE GUIDE: Get Melanie's App To Tackle Your Food Sensitivities! Food Sense Includes A Searchable Catalogue of 300+ Foods, Revealing Their Gluten, FODMAP, Lectin, histamine, Amine, glutamate, oxalate, salicylate, sulfite, and thiol Status. Food Sense Also Includes Compound Overviews, reactions To Look For, lists of foods high and low in them, the ability to create your own personal lists, And More!

2:50 - BEAUTYCOUNTER: Non-Toxic Beauty Products Tested For Heavy Metals, Which Support Skin Health And Look Amazing! Shop At Beautycounter.Com/MelanieAvalon For Something Magical! For Exclusive Offers And Discounts, And More On The Science Of Skincare, Get On Melanie's Private Beautycounter Email List At MelanieAvalon.Com/CleanBeauty! Find Your Perfect Beautycounter Products With Melanie's Quiz: Melanieavalon.Com/Beautycounterquiz

Join Melanie's Facebook Group Clean Beauty And Safe Skincare With Melanie Avalon To Discuss And Learn About All The Things Clean Beauty, Beautycounter And Safe Skincare!

Eat Smarter: Use the Power of Food to Reboot Your Metabolism, Upgrade Your Brain, and Transform Your Life (Shawn Stevenson)

7:50 - Shawn's Background

9:20 - Unique Metabolic Protocols

12:10 - Empowering Patients

13:20 - Clinical Trial To Clinical Practice

16:20 - Deciphering The Science Literature

16:55 - The Microbiome, Diet & Metabolism

19:20 - The Prevalence of Statins

20:00 - Statins and diabetes

21:55 - The microbiome of obesity and leanness

25:30 - pesticides effect on microbiome

27:20 - LMNT: For Fasting Or Low-Carb Diets Electrolytes Are Key For Relieving Hunger, Cramps, Headaches, Tiredness, And Dizziness. With No Sugar, Artificial Ingredients, Coloring, And Only 2 Grams Of Carbs Per Packet, Try LMNT For Complete And Total Hydration. For A Limited Time Go To drinklmnt.com/melanieavalon To Try The NEW FLAVOR Watermelon Salt And Get Free Shipping On Any Order Over $100!

30:25 - Probiotics

33:20 - The Human Immune System

The Melanie Avalon Biohacking Podcast Episode #17 - David Sinclair

35:25 - Epigenetics and the Microbiome

38:30 - Obesity in america

39:50 - Adapting To A Change In Diet

40:50 - Microbes and longevity

43:05 - Prebiotics

44:00 - improving the microbiome diversity

44:30 - weight regain and other symptoms

45:15 - the microbiome of real food

46:00 - "Post"-biotics

46:30 - washing fruit and vegetables

47:30 - exposure to pesticides

49:20 - pesticides and environmental toxins in food

50:40 - the immune system in your gut

52:10 - grains in the human diet

54:10 - gluten and leptin resistance

56:10 - Gluten crossing the gut barrier

57:30 - creating dysbiosis by accident

1:01:10 - food Sensitives

1:03:20 - Sprouting to reduce antinutrients

1:04:10 - DRY FARM WINES: Low Sugar, Low Alcohol, Toxin-Free, Mold- Free, Pesticide-Free , Hang-Over Free Natural Wine! Use The Link DryFarmWines.Com/Melanieavalon To Get A Bottle For A Penny!

1:06:30 - food becoming fat, and burning fat

1:09:20 - The Need To Rename Dietary Fat

1:11:00 - subcutaneous fat

1:12:45 - visceral fat

1:14:05 - intramuscular fat

1:15:40 - structural Fats

1:15:40 - Brown Adipose Tissue (BAT)

1:16:50 - beige adipose tissue

1:19:20 - Does keto increase intramuscular fat?

1:20:15 - the quality of the macronutrients

1:21:00 - do fat cells want to be full?

1:23:30 - resiliency of fat cells

1:26:00 - the role of hunger and calories in over-restriction

TRANSCRIPT

Melanie Avalon: Hi, friends, welcome back to the show. I am so incredibly excited about the conversation that I am about to have. It is with a veritable legend in the biohacking sphere, honestly. It's been a long time coming. I recently read a book called Eat Smarter: Use the Power of Food to Reboot Your Metabolism, Upgrade Your Brain, and Transform Your Life. Friends, I received the book, the title sounded very promising with the topics that it was going to discuss. Words cannot express the level of depth of knowledge of information that I learned reading this book. I know in the health and wellness sphere, there's a pretty good understanding, especially in my community, the biohacking community, oftentimes the keto community, of things like how our food affects our metabolism, affects our body weight. People are pretty familiar with things like insulin and hormones, and how body fat can be stored or gained. But there's a level beyond that, which you guys love, that you know I love where you really go into the detail of literally all the factors affecting ourselves, why we're gaining weight, why we're not gaining weight, how food affects our sleep, our diet, our stress, so many things.

This book blew my mind. I learned so much. I am so excited to be here with the author, Shawn Stevenson, so we can dive deep, deep, deep into all of it. You guys are probably familiar with Shawn. He's the host of the number one health podcast. Yes, number one, The Model Health Show. He is also the author of a prior book, Sleep Smarter, and he's been all over the place, Forbes, The New York Times, ABC, ESPN, so many things, all well warranted. I am so honored to be here right now with him. Shawn, thank you so much for being here.

Shawn Stevenson: It's my pleasure. Thank you so much for having me. I’m excited.

Melanie Avalon: Me, too. To start things off, I bet a lot of my listeners are probably pretty familiar with your work, but for those who are not, would you like to tell listeners a little bit about your personal story? You have a really fascinating personal story with your own relationship with diet and health and fitness. Well, first of all, I’m actually really curious what led you to start Model Health Show? Then ultimately, what led you to writing this book, Eat Smarter?

Shawn Stevenson: Sure. Awesome. Well, starting the show, I've been in this field for 19 years and clinical practice as a nutritionist for over 10 years. We never get this what I’m about to share, some folks get it after certain amount of times, some folks get it right out of the gate. It took me a little bit of time in practice, transitioning from being a strength conditioning coach at a university to having my own clinical practice. We have this tendency in health, when we're a healthcare practitioner, to tell people to do what you're doing. Whatever is working for you as a practitioner, if you think keto is great, you have the people do keto. If you think vegan diet is the best diet, you have people do vegan diet. If you're doing paleo, you have people do paleo. The list goes on and on. It's just a natural human tendency to have folks do what you're doing.

It took a little bit of time, but I ultimately realized that I really had to do what was right for the person, but not just that, do what's right for this person right now where they are in their life, and that is likely going to change. This is quite some time, this is over a decade ago, and we really started to look at unique metabolic profiles, catering things to your what we call this unique metabolic fingerprint. Just diving in and finding about all aspects of this person's life, asking all the questions, doing the things that aren't typically done in conventional medicine. Of course, a lot of physicians would just funnel people to me for this particular purpose, because I would take the time with them. Unfortunately, the system is set up in such a way that most practitioners, whether they get into the field to help people, it's these 5- to 10-minute in-and-out office visits, and they often don't even know the root cause of the patient's issues. I started to ask people about their sleep. Again, the point I’m making is it took me about five years before I started really opening my mind up, and asking about all the things that don't seem like they relate to nutrition. I would ask people about their sleep quality, or asking about their relationships, and their stress levels and all these things. We had phenomenal success.

Even prior to that, we were seeing about 79%, 80%, when folks are coming on type 2 diabetic, they're on metformin, insulin, etc., being able to normalize their blood sugar without medication. Same thing with hypertension, they're on lisinoprils and statins and all this stuff, same thing, somewhere around 75%, 80%, but that 20% of folks who weren't getting the results really bothered me a lot. It's typical in healthcare to think that the person is just not doing what you're saying. Oftentimes, these folks are working harder than everybody else, and yet, they're not getting the results.

Once I found out, for example, how much sleep was influencing their blood sugar, or even our body composition, man, it just really-- once I started to help people to implement simple strategies to improve their sleep quality. Finally, we start to see 90% success rate. Folks who’ve been struggling with weight loss for 20 years, finally the weight comes off and stays off. The point with getting to starting my show is that, after a certain amount of time of doing this work, day in day out, seeing one person after the other, basically, helping them to reverse engineer their illness, I just felt like, “I need to tell more people.” I would have people there in my office, just say they have type 2 diabetes. I actually reverse engineer the condition. I had this image of a pancreas, and liver and all these things on the board, and to see their eyes light up, when they start to understand how their beta cells work in their pancreas and how, “sugar,” when we're eating carbohydrates, sugar, starchy foods, how does that actually end up as sugar in our bloodstream? How does that actually influence insulin? All this stuff, I saw their eyes light up, I saw them feel empowered. It's just like, they actually understand what's happening in their body.

I’m just like, “I need to write this down, or I need to record this,” or something. Eventually, that's what we started doing, and created The Model Health Show, and as you mentioned, I’m blown away. I’m from the Midwest, which isn’t known as the mecca of health in the world. But to have the number one health show in the country, it is really surreal for me. I think a big part of that is that education part, but the thing that I left out, and just for any health professionals listening as well, any coaches, the thing that I left out that we were doing right out of the gate, which I really wasn't intentional about was making it fun, and making it easy to understand, what are often these unnecessarily complex health issues.

The last little piece I’m going to share is, on average, when we've got a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, just gold standard, proving the efficacy of say something like curcumin, curcumin, which is the one of the bio-actives in turmeric. We've got a randomized placebo-controlled trial, demonstrating-- Matter of fact, we've got multiple, demonstrating that, turmeric has anti-angiogenesis properties. What that means is it's able to cut off the blood supply selectively to cancer cells. Powerful stuff. Once we have proof of that, it takes on average 17 years for it to become something used in clinical practice. It makes no sense at the age of the internet, that it would take that long to have proof of something's efficacy that can be helping somebody right now, for it to be used in conventional clinical settings.

What I wanted to do was to shorten that gap, to take the data and make it make sense, because when you're going through and looking at these studies, unfortunately, it's written in a language of academia. It's a language, it's like a foreign language. If you don't speak the language, then it's just going to be very difficult to understand and to extract anything from it. It's often written unnecessarily complex, because they're trying to impress other academics. Taking these very complex subjects and making them understandable, like for example, what learning really is, is taking something that you already know, and creating a connection to something that you don't know.

When I talk about, in Eat Smarter for example, how your metabolism actually works, which is crazy to say this is a first book to take people behind the scenes and actually teach them how their metabolism works? How does the process of fat loss actually work? Where does fat go when you lose it? Does it go to another dimension, is this multiverse stuff? How does it all work? Taking this very complex and seemingly complex process, but how does that relate to going to the movies? How can I make those two things connect? Everybody's been to the movies or they've been to a play. So, I take people through a metabolic theater. What I want to encourage everybody to do is, when you're learning these things thinking about, number one, how can I teach this to somebody else? Number two, how can I make it fun and relatable? Number three, how can I make it empowering? This can be a recipe for big change in our health and in our society.

Melanie Avalon: Oh, my goodness. I love that so much. We're so similar. That's the exact reason that I have this show, is just an incessant need to understand topics, and question people who know it better than I do about it, and then share the findings with listeners. And then 100%, we're also unique, and that's why I also love bringing on people from all different perspectives and just letting it be known that the one thing I know is that I know nothing and that different things work for different people. That was the feelings that I had when I read Eat Smarter, because like you, I love binge reading PubMed studies. It is written in a different language. When I was reading Eat Smarter, and you were talking about the metabolism, I was like, “Oh my goodness, this is what I’m reading about in scientific studies, but I haven't really seen it and a popular book format until now,” which was just so incredibly exciting to me.

Here's a question for you because you talked about all of the different factor-- it's so unique and there are all these different factors that affect metabolism. Let's use diet for an example, to what extent, is it a chicken and egg situation, and what I mean by that is, with the gut microbiome for example, we often see that, and you talk about this in the book, that the gut microbiome can change based on what we're eating, but then a messed-up gut microbiome can also create the issues that we're experiencing. When it does come to diet, how much do you think it's chicken and egg with what we're eating compared to all these other hormones and all these other factors involved?

Shawn Stevenson: Ooh, that's such a good question. Let me start off with demonstrating exactly, how much our microbiome-- we want to make this much more visceral. This is one of the topics, of course, like everybody-- microbiome is on the tip of everybody's tongue, and let's make it more tangible and actionable, and how does this relate to our to our metabolism and our body composition. One of the things that break down, and I'll just give a summation here in Eat Smarter and this was highlighted in the journal, Cell, and they discovered that there's a certain strain of bacteria that actually can block your intestines from absorbing as many calories from your food. This was done on mice, let's be clear first, then we'll get to the human studies. They discovered specific bacteria in mice that can block their intestines from absorbing as many calories from their food. I said us, because of course, a lot of these trials are done using animal models, and unfortunately when you look through the lens of conventional training of conventional medicine, when you find out there's a bacteria that can block the intestines from absorbing as many calories, the thing that you jump to is how can I turn this into a drug? How can I bottle this up, so that I can block people's intestine, so they can eat whatever they want and block their intestine from absorbing as many calories? That's the dream.

Now, unfortunately, it's looking at things through the lens of this in term that we have today which is called “side effects” and looking at the human body in parts. For example, when folks are coming in, and they come in and they've got their list of medications they're on. They're on lisinopril, they're on Celebrex for pain, and they're on a statin. Statins for a while, which still are, but for a while they were the hottest thing on the streets. Statins, they were passing them out like candy. There was even some legislation to get statins into the water supply, little fun fact, but--

Melanie Avalon: What?

Shawn Stevenson: Yeah, that's a whole other conversation.

Melanie Avalon: I did not know that. Mind blown.

Shawn Stevenson: Maybe we could circle back to that. It's just because it just seemed to be so important, because we want to deal with cholesterol in our society, but as I digress, so people coming in on statins regularly. Well, just say, if they're a new patient coming in, maybe 70% of folks, it was crazy. Now anybody can find this data but early on, I saw some concerning data around being on a statin and increase in the incidence of developing diabetes. Now, anybody can go to Dr. Google and look this up, but we come to find out getting on a statin increases your risk of developing diabetes by 30%. The reason that this is that, when we take something that's supposed to be targeting our cholesterol, every single thing that we're taking a medication for it doesn't just affect one thing, your body doesn't work in compartments. Everything is connected. If you take something that's targeting your heart, it's also going to affect your joints. If you take something that's targeting your pancreas or your blood sugar, or you're taking something to target your thyroid, it’s going to affect your brain. Nothing works in a vacuum. There’s no such thing as side effects. These are direct effects. Every single thing we take and we're exposed to affects everything about us.

That is the foundation of what I’m about to share. We don't want to get into that allopathic thinking of like, just give me that bacteria, because when you take-- well, just say, it becomes weaponized as a drug to block people's intestines from absorbing calories, what does that do to your microbiome’s ability to produce short-chain fatty acids? SCFAs, that protect your gut lining, that have important implications for your cognitive function, that help to protect against autoimmune diseases. Are we going to damage them? We start to damage this microbiome ratio by blocking your intestines from absorbing as many calories, by changing your microbiome cascade. What about the vitamins, minerals? I mentioned SCFAs. Your microbes create vitamins and minerals in you for you, so maybe now you're not producing enough B12. The list goes on and on.

Here's the point. I want to use this as a foundation. Now, here's where we get to the visceral part is, and how does this affect directly in human studies. Well, researchers at the Weizmann Institute, and this is what I would see also in my clinical practices, there is a very specific microbial makeup that's associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and excess body fat. We also have a microbiome that's associated with leanness, the makeup of the microbiome, the microbes. I could have somebody send out for a stool sample, never seen them a day in my life and I can get their report back, and I can know with extreme accuracy, whether or not they're obese, just based on their microbiome makeup.

These researchers knew this, and they took fecal samples from people who had a microbiome that was associated with obesity, and they implanted that fecal sample into lean mice. Then, they took a fecal sample from humans who had a lean microbiome cascade and implanted that into lean mice. Those mice stayed the same, even though they're eating the same diet. The mice who received the fecal transplant from folks who had the microbiome associated with obesity, even though they're eating the same diet, suddenly, these mice became insulin resistant, by changing their microbes. Suddenly, the mice gained weight. Suddenly, the mice gained specifically body fat, simply by changing their microbes.

Last part of this, being that I'm from St. Louis, this is one of the most incredible universities in the country, but it's located in St. Louis, it's Washington University School of Medicine. They set out to find if microbiome changes could affect fat loss in sets of identical twins. You don't get any better contrast and comparison than identical twins. Everything about them is the same, except funny enough they do have different fingerprints. I use this term metabolic fingerprint as well.

The prerequisite was to find a twin that had the microbiome associated with obesity, and one that had a microbiome associated with leanness, even though they're identical. Sure enough, they discovered if one twin had a higher ratio of bacteria category called firmicutes, and a lower ratio of bacteroides, they ended up absorbing more calories from their food, even though they're eating the same thing than their twin and they were more likely to gain fat while eating the same diet. The overarching point is that your microbes matter. Your microbes are one of the things that I term an epi-caloric controller. Your microbes determine-- they're one of the factors that determine whether or not you're absorbing calories from your food. It's going beyond the calories in, calories out paradigm, because there are factors that control what calories do in your body. The chicken or the egg, the last point with this is, and I think you know this as well, just like they go hand in hand, they're really inseparable. These are the debates that can go on and on forever, but we need to look at things from both angles, the things that we're doing to damage our microbiome, which we can definitely dive in and talk about that.

Coming into the situation with the healthy microbiome in the first place, how does that happen to protect us against fat gain? What we've seen is that over time, by the way that we eat as a culture, by the things that we're exposed to as a culture, one of the things that I shared and highlighted in Eat Smarter was, because we have data on this now. We have a lot of very eye-opening data on how pesticides and rodenticides and herbicides damage your microbiome, specifically creating damage to the genes of your microbes. This is serious business, serious stuff because over 99% of our genes that we carry are not our genes. They're the genes of our microbes. If we're going gene for gene, of course we are much bigger, but gene for gene, over 99% of our genes are not “human.” They're from the microbes we carry.

What the researchers discovered was that looking at the microbes, the microbial makeup of somebody eating more of an indigenous diet, they're eating more of a hunter gatherer diet, closer just to how we evolve, they have on average four times more bacteria, four times more species of microbes than the person eating the average western diet. Just to say, I’m just going to throw this out, these are not exact numbers. Just say, I have 10,000 species of microbes in my gut. A person eating a natural human diet or something closer to what would be a natural human diet we evolved with have 40,000 species. What the researchers noted is that as your diversity of microbes goes down, your rate of obesity goes up. As your diversity of microbes goes down, your rate of insulin resistance goes up. As your diversity of microbes goes down, your rate of heart disease goes up. The list goes on and on. There's an inverse relationship as we lose species of bacteria, and so of course we could talk about some things to help to improve this ratio, but that's a lot to unpack, but I hope that it gives a good summation.

Melanie Avalon: I love it. I’m so impressed that you brought it all back to the original question I forgot about the chicken and egg. I have a super, super random question. I’m so fascinated by the microbiome and the studies. Have you seen the studies where even when patients are given dead probiotic strains that it still has effects on our body?

Shawn Stevenson: Okay, so you're opening the door here that-- this topic is so-- I love how you talked about earlier, and I just heard this quote on a song, there's so many things I want to say. It's like the matrix right now, there's so many things I want to say, so many things to choose from. There's a song that I just heard that says, “The wise man knows a wise man knows nothing.” We know so little about how everything works. We're spinning around in the middle of the universe on a glorified snow globe. Literally, all the elements that make up our bodies came from stars, like supernova. We're just trying to be less dumb, that's what the process really is right now. That's okay, there's this beautiful thing throughout history. Great minds have just really gotten to a point where they just realize like, “Man, we know nothing. We know nothing," and being content with that, but this should not inhibit our ability to discover, to explore, because the truth is, whatever your truth is. There's nothing more powerful than that.

Now, I’m saying that to say that this conversation today, even about-- by the way, we've discovered bacteria frozen for thousands of years that's still active. You can still put in a culture, and they can replicate thousands of years. They should be “dead,” but that's not how it works. They're like Captain America, coming out of the ice, and the same thing with viruses. Viruses are the most-- again, anything that I say, I encourage folks to go and look up, because it's just really amazing. We have more virus particles in our world on the planet than literally anything else. There is nothing even remotely close to the number of virus particles in and on our bodies, and on planet earth in general. We have over 400 trillion virus particles in and on our bodies right now. These are considered to be nonliving, but they kind of are. It's just like this very interesting nuance, because this thing, this non-living entity, can literally jump into the captain's chair of your cells and take over. It's so strange like zombie, maybe this is why we're so obsessed with zombie movies and shows, I don't know, but it's like this process.

A little fun fact too is that the human immune system itself, it is derived from viruses. It's built on viruses, not that viruses helped to develop, but it literally-- like our mitochondria, the best theory that we have is that our mitochondria is how bacteria integrated with our human cells and became a symbiotic relationship. That's what happened with our immune system. We developed an immune system of virus-- we had a virus that faced off against other viruses to develop the highly sophisticated human immune system that we have today. Actually, when they mapped out the Human Genome Project, which again, they thought we were going to have hundreds of thousands of genes that shows our vast diversity in our overbearing dominance in the animal kingdom, but it was like 20,000 genes. There are some insects that have more genes than us.

What they did discover, of course, is that epigenetic influences, a single gene can do-- there can be thousands of different outcomes from a single gene. The point being that, when they mapped out the human genome, they discovered that our genome, the human genome, the makeup of humans, we are approximately 8% endogenous retroviruses ourselves. The human genome itself is 8% virus. This is something that's nonliving. There's so much nuance there. You just opened up a whole can of worms for me with that question. It's so remarkable. Again, we know so little of how all this stuff works. The things that we do know are pretty cool.

Melanie Avalon: I’m so excited at this moment. I am haunted by the concept of what drives the virus. I had David Sinclair on the show. I was like, “Please just explain to me what is motivating a virus to do what it's doing compared to bacteria, and why do we call bacteria “alive,” and a virus not alive?” I’m just so fascinated by this whole topic. Speaking up about epigenetics and still staying in this world of the microbiome, do you think our DNA has a recorded genetic awareness. preexposure even necessarily to these microbes of these different microbes? What I mean by that, I’m going back to the study about how even a dead probiotic has an effect on the immune system, which suggests to me that the immune system has an idea about what that bacteria means to it? I’m getting a little bit esoteric. Where do you think the knowledge of the body lies in regard to the microbiome? Do you think with that knowledge that-- it goes back to what you're talking about, about us being all individual. Does that mean some people are destined to only have a good relationship with a certain type of microbiome and a certain type of diet, or do you think anybody could adapt any diet and then the microbiome and the immune system would adjust accordingly?

Shawn Stevenson: I love this question so much. To pivot back for one second, one of the studies that I mentioned earlier, I don't know if I mentioned where the study came from, but it was published in the journal, Nature, and it revealed that the more diverse microbiome that we can have, the more diversity we have is associated with the greater number of health benefits. Again, as our diversity goes up, our body weight tends to go down, as our diversity of microbes goes up, insulin resistance tends to go down. With that said, humans evolved-- If we look at, again, any humans who work-- again, more living like an indigenous type of lifestyle, so closer to their origin, we see this vast array of microbe diversity that we simply don't have.

Also, one of the little interesting things that I talked about in Eat Smarter is how, and this was one of the coolest and crazy studies, and this was from researchers at Stanford, discovered that gut microbes in digestion are cyclical, and in sync with seasons and environmental conditions. We've been doing this a very long time. You mentioned, even “dead” or inactive microbe exposure, any of these things can still have an impact on its association with human cells. We're used to having a diverse exposure to different microbes, which we don't have today, which is a big part of the reason that we are so susceptible to disease, so susceptible to infections.

We are not well here in the United States. We're not. Honestly, we're the sickest nation in human history, self-inflicted. I’m not talking about bad water. I’m talking about self-inflicted chronic diseases. The Journal of the American Medical Association, this is 2018, which we knew this already, but now we got data, which we just bring people back to the data, because it tends to cut through. They affirm that poor diet is the number one cause of our epidemic of chronic diseases. I just checked out the most recent data yesterday. We have about 240 million Americans who are overweight or obese. It's unbelievable. Unbelievable. 43% of Americans are clinically obese. We're on track within the next couple of years here, and COVID has helped a lot, with getting this number there quicker. We're almost at 50%, which is in the next couple of years, 50% of our society is clinically obese. Obesity every year, every year-- First of all, obesity is connected to 60 different chronic diseases, and every year, over 400,000 people die with issues related to obesity and you hardly hear a word about it. About 50% to 60% of the US population has an advanced degree of some type of heart disease as well. 125 to 130 million Americans are diabetic or prediabetic right now. It's insane.

This is the part, this invisible world, we're afraid of something invisible, but the invisible world within our bodies we're not giving a lot of attention to unless you're in the know. Even then, it's still just like here today, gone today. We're not really understanding how important this is, with understanding our microbes and how we associate with the world. Just going back to that question, and what I would say is, we're used to a lot of exposure of different microbes, cyclical exposure of microbes. Now, could we change and adjust to a different diet? Yes, absolutely. Absolutely, we can. However, is it optimal? That's where the debate can happen, because obviously, most of us here in this-- even if we're eating healthy, it might not be what your genes expect you to eat. Like your closest ancestors, for example, my wife's from Kenya, for example. She's got a much closer association to her diet, than I do here in the United States. I’m not as close to my lineage. If you've got families coming over from Italy, what have your ancestors been eating for centuries? If you're connected to that-- or even thousand years or so? Maybe eating closer to that is going to help to proliferate certain microbes that really protect you against illness that--

David Sinclair's a friend as well, that you mentioned, these longevity genes, because our microbes have a lot of interaction with what's happening with our genetic expression. Yes, we can definitely adapt and change to different-- Humans are freaking resilient. We're just resilient to different diets, even terrible diets. We can be so messed up, we can have all the things, we could have diabetes, we could smoke every day, and still live to be 70, 80 years old. We're incredibly resilient. That's where we get into this conversation of you're not living longer, you're dying longer, and quality of life, actually feeling good, and having all of these incredible benefits of being here in this human form, and this opportunity.

Yes, to answer the question, yes, we definitely can adapt to different diets and our microbes will inherently change, because and here's the point, this is a big takeaway for everybody as well, when talking about, okay, so how do we do this? How do we improve the diversity of our microbes and make us more adaptable to different dietary inputs? For example, this term called metabolic flexibility. This is largely based on your microbes. What I’m about to say, people have heard about, but we're going to dive deeper into it. We put these microbes in this category of probiotics. Probiotics for life, is what the word means. Probiotics, sounds good. Early on in my clinical practice, I was putting everybody on probiotics. Again, this is like 15 years ago that I was doing that. I was really missing the point. You can take and I was getting people these-- it took like three years of fermentation to make these fancy pants, probiotics, but it's not going--

Melanie Avalon: You're making them yourself.

Shawn Stevenson: No, no, no. It was really wonderful company. No. Here's the point, it's going to be not totally wasted, but largely wasted on your body. These probiotics cannot proliferate and colonize in your gut, if they don't have their source of food to eat. If they don't have their “prebiotics.” This is the food for our microbes. If we want to improve our microbiome ratio, and improve our number of species of microbes, we have to improve our intake of prebiotics. You can go to Dr. Google and look up prebiotics and it's going to be things like artichoke, Jerusalem artichoke, asparagus, onions, garlic, but even with that, we're really missing the point. The point is this, every single real food functions metabolically as a prebiotic. Every single real food functions as a prebiotic. The number one thing that we see in the data-- and again, I shared a peer-reviewed study in Eat Smarter to affirm this, is that the number one thing we could do to improve our microbiome species, the number of species, is to simply improve the number of foods that we're eating. The number of different types of foods, because and I know some people listening, even if we're eating a healthy diet and we're feeling good and we're eating things that we enjoy, we're winning, we can tend to get caught in this meal prep gone awry, where we're eating the same things over and over and over again.

Now, here's the thing, and I've seen this countless times. We can do that and get great results everything's going well, we'll just say for a year. Then, all of a sudden, the weight starts creeping back on. All of a sudden, we start maybe having some kind of a strange allergy that developed or some arthritic symptoms, the list goes on and on, not realizing that behind the scenes, our microbes are literally moving out, because they're not getting fed the prebiotics that they need to stay in our system to proliferate. Number one thing we could do is to simply increase the number of different foods that we're eating, so just be more intentional about it. Each week maybe, eat two different foods, for example, something as simple as that.

The last part is this, this is so simple but so powerful. How do we increase those microbe species is directly from eating different foods? When you eat a real food, you're eating that food’s microbiome. When you eat a food, you're eating that food’s microbiome. A berry has a microbiome. An avocado has a microbiome. Kale has a microbiome. Whatever real food you can name. A twinkie? I don't know. Possibly, this maybe that's where you get the mutant strains of whatever microbes, but when you eat a real food, you're taking on that food’s microbiome and incorporating it into your own matrix, is so powerful, so powerful when you start to see through that lens. When you allow our probiotics to proliferate and colonize, and create post biotics, they're creating all of these beneficial compounds in us for us. It starts with the foundation of the prebiotics.

Melanie Avalon: I’m never going to look at the word prebiotic the same way again. I hadn't thought about that, but really, technically, every food, unless it's like, I don't know if plastic can feed gut bacteria. As long as it's capable of feeding bacteria, it technically would be a prebiotic. If a person can eat organic, are you a fan of not washing the fruits and vegetables to get more of the species?

Shawn Stevenson: All right, this is another great question. I love this. [laughs] All right, one of the biggest misconceptions, and I’m not a big fan of misconceptions. I want us to all be right, especially when people just they're doing something, they think it's benefiting because there might be a placebo effect to it, but this idea of using a veggie wash, and washing your berries off, and getting rid of helping to wash off pesticides, for example. That is simply not how it works, is simply not how science works. I’ve done so much research, and also sharing study after study after study on this and working with some of the top people in the country on these subject matters.

We'll just use chlorpyrifos, for example. Chlorpyrifos, one of the most widely used pesticides. We have peer-reviewed evidence on people being exposed, farmers being exposed to chlorpyrifos, and the radical incidents. For example, pregnant women radical, it's scary, and you when you go and see some of the documentaries have been done around this, ugh, but radically increase in incidence of having, argh, so difficult talk about. [sighs] Having developmental issues for their children. Their babies being born with defects, specifically of their brain and their nervous system. Chlorpyrifos is just terrible. It's a neurogenic pesticide that's designed to disrupt the nervous system of pests. Not understanding that this very small thing that is trying to kill and disrupt the nervous system, we are made of very small things, we’re made of these things. Now having real world data affirming how chlorpyrifos and other pesticides which there are over 50,000 pesticides approved by our Environmental Protection Agency to be used in the growing of our food. These agents, see, they're supposed to be protecting the environment, protecting you, you're part of the environment, it's just unbelievable. It's so corrupt. That's a whole other story.

Seeing that, this is happening, in populations being exposed to chlorpyrifos and damaging their microbiome, not just that, but of course, the developmental issues and also skyrocketing rates of miscarriages. Having this exposure over time, but the food itself that's being grown with this stuff, these chemicals are integrated itself into the food itself, just like it would do with us, it becomes a part of our tissue matrix. We're very evolved to where we have a dynamic system of eliminating toxins, not everything, some stuff can get caught up in our tissues, some stuff can get caught up in our liver, for example. Your liver really takes the brunt of exposure from environmental toxins. It's integrated into the berry itself. It's a part of the strawberry’s matrix, the cellular makeup of that strawberry. We can't wash it off with a fancy veggie wash. It's integrated itself with the strawberry itself. It's a very superficial idea, cleaning stuff off that kind of thing.

Now to the original question of, what about the microbes washing it off, I don't see that as an issue at all if you're getting some organic berries, especially, if you're getting from a farmers’ market, or organic section, whatever, yeah, especially just with that borderline healthy immune system, our immune system is designed to specifically target and regulate the exposure to pathogens, if everything's working well. Getting into your stomach, stomach acid is not a pretty place to be for microbes, that the body does not want to be clear. The majority of your immune system, as many folks have said, but to really get this today, the majority of your immune system is located in your gastrointestinal tract. It's there for a reason. We're designed like that for a reason, because through our evolution, what you put into your mouth, could potentially kill you very quickly. Your immune system needs to be there front and center to make sure that what you're bringing in is okay.

A lot of folks don't realize this, that when you eat a meal, we actually have an increase in stress hormones, because, again, this is a somewhat stressful event, like your body has to really take and put a lot of energy towards, making sure that what just came in isn't going to kill you. That's the kind of negative side, but on the positive side is, it's there front and center your microbes, this incredible process of taking that food, and now, the energy is being used to turn this food in to you. Just saying strawberries, now we're going to turn these strawberries into human tissue. Man, that's like freaking David Blaine stuff, that's like David Copperfield cellular magic. This is why it requires so much energy, and the immune system needs to be there front and center to make sure that everything is going according to plan.

Melanie Avalon: It's so mind blowing. I have two questions that both relate that go different pathways. I guess first, speaking of what we are bringing in so, you spoke a lot about evolutionarily what we are adapted to, and one of the things that I loved in Eat Smarter was your very nuanced perspective of something that I think is often-- Well, I'll just ask you. What are your thoughts on grains? You tell a really great story about being put on a certain restrictive dietary protocol at one point and being encouraged by a practitioner to bring back certain foods that are often deemed toxic overall, like grains, legumes, at least in the paleo world. What are your thoughts on grains?

Shawn Stevenson: It is a great question as well. I was saying one of the analogies, like there's two sides to every slice. There's two sides to every slice, and the people who really educated the public, which is massively needed on some of the potential, even deadly effects of the consumption of grains, especially, this very hybridized dwarf wheat, this conventional wheat that folks are eating. Dr. William Davis, Dr. David Perlmutter, Dr. Steven Gundry was just at my house the other day, he's the lectin guy, he brought lectins to the forefront. These are all my friends.

Melanie Avalon: I’m interviewing him pretty soon. I’m so excited. Dr. Gundry.

Shawn Stevenson: Ah, The Energy Paradox is the new one, you're going to love it, you're going to love it. These are all my friends and colleagues. I love these guys. Again, there's two sides to every slice. Of course, I break down the potential hazard here. This was one of the things I saw a lot of success with in my clinical practice is just getting people off grains, because there's no nuance there. There's no nuance. One of the studies that I shared in Eat Smarter was-- I like to look at the dynamics that people might overlook that are very visceral. One of them was this really interesting peer-reviewed study on how the consumption of gluten was creating leptin resistance in people.

Leptin is this glorified leader of our hunger and satiety hormone teams, is the leader of the satiety hormones. We can dive into just spend a bunch of time talking about leptin, but leptin is actually produced by your fat cells to basically inform your tissue matrix, your brain, your system overall, that you're satisfied that you've got enough in stock. You would think if you've got a lot of fat, and you're producing a lot of leptin, which folks who are obese, they have a lot of leptin. The receptor sites, it's a metabolic DM, a metabolic email coming in. Once you accumulate enough fat tissue, and you've got all this leptin being produced, that message to stop eating starts to go to spam. It's not actually getting picked up, because there's a downregulation the receptor sites for leptin. One of the things that can superficially or artificially just encouraged us to happen is gluten can damage the function with your leptin sensitivity. Again, another reason why we have this ravenous chronic hunger, cravings, all these things associated with gluten that we now know about. I do break down that science and how all this stuff works, but then there's another side.

As a matter of fact, I'll share one other little piece, which I know somebody's probably already talked about on your show before, but I just want to share this. In Eat Smarter, this was in the British Journal of Nutrition. It's the British Journal of Nutrition. One of the most prestigious journals, especially targeting food, found that there's a lectin in wheat called wheat germ agglutinin, which again, a lot of people have probably talked about WGA. The crazy thing about it is that it's able to basically punch its way through your gut lining intact and enter your system circulation in your body. It's very abnormal. It just gets in there, and just starts like Mike Tyson in your gut lining. To the point that, this can start to break down the doors of your intestinal lumen and create, where other stuff is able to get into your system, it's going to set off an immune response. Then we get into molecular mimicry and inflammation and autoimmunity and all that stuff. Again, clearly there are issues with lectins, with WGA, with gluten, the list goes on and on.

But there's another side to the slice. A few years ago-- wait, how long ago is this? Maybe seven years ago, because of me using my body as a walking-talking laboratory and experimenting with all of these different diets. Man, I've done have tests so much, I've done so much crazy stuff like you. It's unbelievable, all the different diet protocols, but I won't just do it for a week or two or a month. I'll do it for a year or two or five, and see what happens. I do not recommend that, especially if there's good science showing that it's not healthy long term, for example. Anyways, I created annoyingly, because the science of the microbiome-- really at that time, I was just starting to look at that in my clinical practice, just started to sending people to get stool samples, all the stuff, but it started for me, because come to find out I had some dysbiosis, which this is one of the biggest, if not the biggest underlying epidemic, driving so many problems.

Now, you might have direct gastrointestinal tract pain. Pain, bloating, discomfort, but then on the other side, you might not have any symptoms at all related to what you would think-- if you have like a-- It used to just be called a “tummy ache,” but now it's got all these different names, IBS, etc. But you might have skin issues relating to this dysbiosis. You might have developed rheumatoid arthritis. You might develop thyroid issues. The list goes on and on. Your symptoms, this goes back to our genetic uniqueness, and how these epigenetic influences affect us as an individual. Anyways, I was dealing with this gut dysbiosis and I was working alongside a physician friend of mine. At this time, I had taken on-- I'd done a few years of vegan protocol, a couple of years of raw food protocol, a couple of years of paleo protocol. I think I might have been doing keto protocol at this time. I don't remember which protocol I was on, but I pulled out all grains and legumes. The physician that I was working with, after he looked at my micro cascade, and I looked at it, we were like, “Okay, yeah, we see there's some dysbiosis.” For me, it's like, “Okay, just take the probiotics, get the things to try to dominate and get the other stuff out of there.” But it's the prebiotics. It's the prebiotic aspect.

My guy was like, “Well, Shawn, I’m going to recommend that you add in some beans, and some sprouted bread.” In my head, I’m just like, “No way, I’m not doing that.” What I did was, I did everything, but that. I took the probiotics, I took some kind of-- and this is again catered to me, some different, very specific targeting the overgrowth of microbes that I had unfriendly flora, so antibiotic for that, as well. This doesn't have to be a pharmaceutical, there's “natural" versions of antibiotics. I was doing all the things, but I didn't add in the prebiotic strains but come to find out later, these particular bacteria that I was really low on, loved that prebiotic. Just to share with you guys, and this is published in a peer-reviewed journal, Microbial Ecology in Health And Disease. Gut biosis involves the breakdown of pivotal mutualistic relationship between gut bacteria, their metabolic parts, and our immune system.

To put it directly, I had an overgrowth of opportunistic bacteria, and was lacking on key friendly strains of bacteria that helped to keep them in check. I came back in, I got retested after, maybe it's about a month, and it wasn't much difference. I was already feeling better, my gastrointestinal pain and bloating. The reason that I knew that this was happening was that my food sensitivities. I would eat a meal and start to feel discomfort. I started to, just eliminating all these foods until I got to the point where I was afraid. I had some fear about eating. I was just eating my safe foods, and it was just not normal. It was not okay.

What I did was, okay, so I listened to him, I relented, and then I added in some beans. I looked at, and this is what, my friend, Dr. Steven Gundry, talks about. Number one, using a pressure cooker. Number two, what if they're sprouted? This helps to reduce dramatically, and I share many studies on this, the lectins and the antinutrients that are in these food products. I started adding in some beans, and I was doing the sprouted grain bread, like I'd have a couple slices a few times a week. Man, I retested and my gut makeup was incredible. All my symptoms were gone. They've been gone since. That was something I was dealing with for two years, on and off. When I added these foods in and again, if I didn't do this firsthand, I would not believe it, because there's just too much negativity attached to those foods, I just didn't see them as being helpful or even curative for anybody. Now, what I would automatically go to is like, “Well, there had to be some other foods to do it.” Well, these were pretty damn easy. I didn't have any side effects, just positive benefit personally. This is why we have to do what's right. We cannot think that our way of doing things is going to be best for everybody, and then going screaming from the mountaintops that everybody should never eat beans again.

Again, my wife is from Kenya. There's a lot of Indian synergy in the cultures as well. They have been eating beans for thousands and thousands and thousands of years. Then we get into conversation about, the advent of agriculture and what that did to us. Well, again, there's things that have nuanced there. Just to share this really quickly for everybody. This was published in the Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, found that simply sprouting the grains is an effective way to dramatically reduce phytic acid, and increase the nutrient absorption. That's another thing I was worried about is, is going to block my nutrient absorption of other things, like zinc, for example. Also, I mentioned WGA earlier, this was in the Journal of Nutrients, found that levels of WGA are completely undetectable in cooked whole wheat products. There's a lot of nuance there that's not talked about. This is not an advocation to go and start making sandwiches right now. But this is just something that we need to look at the other side, the potential benefit for some folks. I definitely don't eat a lot of bread very often now. I just don't eat. I don't feel I need to, and I'm just not drawn to that food, but I’m not averse to it either. Everything is an option. If it has a root of human use for thousands of years, it's still an option in my mind.

Melanie Avalon: I really, really love that perspective. I think it will really resonate with a lot of listeners, especially what you were saying about the food fear, and the restrictive diets that people get into, and it can be very, very overwhelming. Even if that doesn't straight up convince people to jump on the legume, or even potentially sprouted grain train, maybe it will have them thinking about the potential of it. A huge topic I would love to dive deep into, you were talking about the magic of our bodies, and the ability to turn a strawberry or a twinkie into our body cells. A huge part of your book, Eat Smarter, is what literally happens, and how what we eat becomes fat. Also, on the flip side, how we burn fat.

One thing I love that you said, it's something I think about all the time, and honestly, I think it's a travesty that the word 'fat' is used to describe both dietary fat and body fat. Even though carbs, carbs can become dietary fat, but we don't call them fat. I think you said something like we call blueberries blue, but they don't turn as blue. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about-- oh, there's so much, but talk a little bit about dietary fat versus body fat, body fat communities, what determines if we use our burn it? There's so much there, I'll just let you speak whatever resonates, or whatever's on your mind.

Shawn Stevenson: Sure. Yeah, that's a great question. This topic in of itself-- unfortunately, there's an issue here with semantics. There's an issue with language because as you mentioned, when I was in college, when I was in my nutritional science class, the big thing at the time, which for years, and still has its hooks in so many people, was to recommend the patients you work with to really be careful about eating fat, low fat everything, low fat everything, low fat dairy. I was going to say, I’m just going to say it, market really mess up everything. They just start putting low fat on everything. It became a fat phobia. But what it was is a leverage point with semantics, because there was this belief, that if you don't eat fat, if you can reduce the fat that you're consuming, then it's not going to end up as fat on your body. This was seen as the same thing. I don't want to get fat, so I’m not going to eat fat.

That same logic is thinking that if I eat blueberries, it's going to make me blue. If I eat green beans is going to make me green. That's not how things work. Biochemically, that's just not how the systems work at all, not even remotely close. That as a tenet, I think it's been a great disservice to our society. I’m making, and this is with Eat Smarter, and I’m so grateful. When it came out, it was the number one book in the United States for the first couple of days of all books, including fiction and nonfiction. Getting this information out to more people, and having this advocacy, and one of my big missions with this is to change the name of dietary fat to something else so we can end the confusion.

Melanie Avalon: That would be amazing.

Shawn Stevenson: Right, but there's definitely a way. There's definitely a way. It's going to take time. There's so much fat phobia, and because of that, we could change the name to lipids, we can just call it dietary lipids. We can call it, I don’t know, flexies? Fats and sexy? I don't know, we can just pick up something.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, I’m thinking like, come up with a completely new word.

Shawn Stevenson: Right. We can come up with a completely new word, we can come up with just use something that's already there in the science. The bottom line, we need to change it. We need to change it, so that there's no more confusion, because fat and food, and fat on our bodies are two totally different things. Totally different. What does that fat look like on our bodies? That's one of the things I really wanted to demystify, because one of the biggest issues in our culture, of course, is excess body fat, and this is something that's very attractive for a lot of people is eliminating fat, “burning fat” and really helping to change their body composition. Not often as it should be for health reasons but more so for, people want to look good. We all want to look good, feel good. I definitely understand that, but there's an underlying lack of education on the thing that we're trying to target, so we're trying to burn fat, but we don't even really know what it is, and understand how amazing it is.

I broke down, I talked about the different fat cell communities in the book, which some of these I’m going to share folks have heard of, and then maybe I throw in a couple that you may not have heard of. But number one, we're targeting fat, we're talking about fat loss, we're targeting storage fats, they're called storage fats. One of them is subcutaneous fat. That's the fat right underneath your skin. It's the fat on the back of your arms, your booty, even you can have some subcutaneous fat on your belly, but this is stuff you can pinch. The fat on your legs, subcutaneous fat. We've got subcutaneous fat, that's one fat cell community, storage fats. It's called a storage fat, because literally the fat cells themselves get filled with contents.

When we're burning fat, we're not burning fat cell, we can't indiscriminately kill fat cells. There's certain metabolic processes, we'll just use hormone-sensitive and lipoprotein lipase. Hormone-sensitive lipase basically, it's like a key opening up that fat cell to get it to release its contents. Lipoprotein lipases storing, getting the fat cells open up to store fat. It's a very rudimentary understanding, there is glucagon involved, insulin all this stuff, but again, we go through that in depth in the book and make it really make sense. Bottom line is, we're getting the fat cell to empty its contents, so that it can be shuttled to its endpoint to be actually used or “burned” at the mitochondria. That's just one endpoint. There's also nuances some other ways, but predominantly getting it to the mitochondria. Here's the thing, you can get the fat cell to open up and release its contents, but it can get reabsorbed somewhere else. You've also got to be able to complete the process. Anyways, we've got this fat cell community of subcutaneous fat stored with contents, and the fat cell itself is what grows. Your fat cell can grow hundred times its size filled with stored energy, triglycerides, etc.

Now, subcutaneous fat. The other type of fat a lot of folks know about is visceral fat. Visceral fat also known as omentum fat, which is derived from, I believe, is Greek or Latin, but it means fatty apron. It's the fat around your belly. It's the deep abdominal fat that really puts a lot of pressure on your internal organs. It’s the belly fat is much more difficult to get a grip on. These two types of fat cell communities, and visceral fat is the one that's most identified in the literature, mountains of studies, to be the most dangerous. Higher rates of insulin resistance, higher rates of diabetes, heart disease, cancer, the list goes on and on. Visceral fat is something that your body generally doesn't just jump right to making visceral fat, except today the way that we eat. Some of the abnormal things that we're eating, but it's like systems of banking where you've got subcutaneous fat, which is the first place to get energy stored and then the visceral fat will be a little bit more down the line, but there are processes that can bypass and create more belly fat. Even our sex, men and women store fat differently. Product labels on processed food you're buying, doesn't account for any of these things, these differences.

Visceral fat, subcutaneous fat. Another type of storage fat is called intramuscular fat. When I was in college, I was taught that fat and muscle are dichotomous, they have nothing to do with each other. You just want to burn fat and build muscle. But intramuscular fat actually works as on-site energy for your muscles to work, and to get a picture of what that looks like, if you think about the marbling of a steak, that is intramuscular fat. All three of these are storage fats. You could have too much intramuscular fat and develop a condition we call chubby muscles. These are all the fat cell communities that we're trying to target.

Here's the beautiful part about it. These fat cell communities are one of the greatest things, one of the greatest evolutionary adaptations that humans have developed. They've kept us alive. It is our ability to store energy and utilize that energy later that has enabled us to become the people that we are today. Our fat is amazing. It's helped us to survive and has so many different metabolic jobs that is doing. The problem that can come up though is that it's very good at doing this job. It can be very clingy. Especially, when it's bombarded with energy, it is just very good at storing it. It's only going to use that energy when it really needs to. It's just simply doing what it's designed to do.

The other fat cell community are-- the fat cells we talked about storage fats, then we have structural fats in the brain, which is something totally different. You don't burn your brain fat, thankfully, but then we also have the types of fats or fat cell communities that actually burn fat for fuel. A lot of folks today know about brown adipose tissue. I've been talking about this for a very long time generally in relationship to like cold thermogenesis, for example, but your nutrition, as we dive into in Eat Smarter has a big impact on your brown adipose tissue, which again, brown adipose tissue is a type of fat that burns storage fats. The reason that it's brown is that it's so dense and mitochondria is the endpoint, is the end station for “burning "fat. This is why so incredible. Babies have a lot more of a ratio of brown adipose tissue, evolutionary adaptation to help us to protect against hypothermia for example. As we grow older, our ratio of brown fat just shoots right down, but we all have some. It's mostly around our collarbones, shoulder blades, down our spine. There are things we could do to increase the activity and production of our brown adipose tissue. That's one.

Then we have beige fat cells. Beige fat cells. Beige fat is unique from all the different types of fat cells, have their own stem cell precursors. Beige fat can actually become brown fat, or it can become white fat or white adipose tissue storage fat. It can become the type of fat that burns fat, or the type of fat that stores fat depending on epigenetic influences. One of those, funny enough, and I'll just throw this out there because I was shocked, I was shocked to see it. This is not an advocation for this, but coffee appears to nudge beige fat cells into the brown fat, burning fat domain. Researchers, and I broke the study down in Eat Smarter, used FMRIs and actually looked at the activity of brown fat, and so coffee was consumed. Number one, of course, nudging beige fat to become brown fat, but seeing the brown fat parts of the body light up, just lit up with activity when drinking coffee. Then, we get into the nuance of the type of coffee, how much and all this stuff, but that's for another time. Just one of those really interesting things, there's so many things we could do. Ginger is actually found to have an impact on hormone-sensitive lipase, that specific enzyme, that goes and signals that fat cell to open up so that we can use the contents inside. The list goes on and on.

Those are the different fat cell communities. Just to get a little bit more understanding, a sense of closeness to it and understand that our body fat is doing what it's designed to do is very good at it. We evolved having times of eating, and not eating. Today, we just have constant access to food. Does this mean we need to starve ourselves or to do all this fasting? There are definitely some benefits there. But very simple changes can help all of these processes to work in synergy. Your storage fats, your fat cells that burn fat, protecting your structural fats in your brain, we talk a lot about that and really improving the performance of your cognitive abilities, your ability to focus, your memory, all this stuff, with all the incredible evidence we have today, but all of our fat cell communities are incredibly important.

Melanie Avalon: Yeah, for listeners, you have to get Eat Smarter, if any of that was even remotely interesting to you because it goes even way beyond. Everything that you just said, you get all of the really deep specifics, and it's so fascinating. I just have two really quick questions. One is a super rabbit hole, but the intramuscular fat. They often sound like keto, low carb diets that our muscles get better accustomed to running off of fatty acids, compared to carbs. Do you know if that increases intramuscular fat as well? Or, is that a different thing, like the ability of the muscle to run off of fat versus storing fat in the muscle?

Shawn Stevenson: I can't say for certain if intramuscular fat is going to be specifically functioning differently, based on the fuel input, but it's possible. It's definitely possible. Of course, your brain starts functioning differently, running differently when we have different fuel coming in. We're talking about ketones. Your body's incredibly adaptable. But the intramuscular fat, it's just really doing what the rest of our fat cells do. Here's the thing, you can overeat any of the macronutrients and lead to fat storage. It's just, number one, the quality of the macronutrients that we're eating in the first place, the impact that it has on our appetite regulation, meeting our nutritional needs, filling up that nutrient bank account with all the vitamins and minerals, and all the things that we need, our essential amino acids, etc., to really function optimally. But you can also be on a high-fat protocol and increase your intramuscular fat. It's more so of, also your genetic predisposition, how you store your fat, and having the right balance of the macronutrients for you to make sure that they're running optimally.

Melanie Avalon: Okay, yep. So many factors as per usual. Then, one esoteric question about fat. Do fat cells want to get fat? If a fat cell is empty, can it be okay with that or is it going to aggressively want to be full and by-- I don't know if it's the fat that wants to be full or the brain that wants the fat cell to be full. I’m just wondering if when people lose fat from their fat cells, if those fat cells are destined to want to be full.

Shawn Stevenson: Oh, my goodness. I love talking with you. It’s such a great question. I love the fact you said this is esoteric. It's the fat cell’s purpose. It comes into existence-- its purpose is to store fat. It's my purpose. What if you're not able to fulfill your purpose? You also got to look at the other side of the purpose, which is to provide that energy. It should be like an in and out, like I’m going to work and do my job, and I have some time off. What we do know, and this is one of the most powerful things for us to understand that we break down and articulate, especially just seeing people who've developed this state of learned helplessness, because they've tried so many things, they're just wondering why their body will not cooperate.

As I mentioned before, you can't indiscriminately kill your fat cells. When you're born, you have about the same amount of fat cells throughout your life. You do have and they die off, but you produce them at about the same rate that they die off. The catch to this, however, is when we venture into obesity. When we venture into obesity, we actually start to have more body fat cells, but we also have a counterbalance of them dying off as well. So, now we're producing more, and these very, very hungry fat cells, once we've entered to into obesity, they become accustomed to hanging on to a lot more energy. Now, when you pull back and you change the nutrition, change the way that I was eating growing up, for example-- 30 of my close family members, 28 of us, my family members are obese. Eating the way that we were eating, once you pull back on that stuff, and you start to eat more nourishing food, some people might-- they're taking on a specific caloric restriction. Again, we talk about the nuance with caloric restriction in Eat Smarter, because there's epi-caloric controllers.

Anyway, so they changed the way they're eating, the fat cells are accustomed to being filled with energy. Wow, what the data shows on these fat cells being very resilient, specifically in relationship to your hunger and satiety hormones, which driving you to basically seek out more food, it makes it very difficult. When somebody loses a lot of weight because the metabolism has changed so much. These fat cells have really-- It isn't just that their purpose is to store energy anymore, they've taken on, my purpose is to store so much energy as a competition. Now, all of a sudden, it's taken away. What purpose do I have? This gets in the conversation and working with people over the years and the TV shows and things like that, you see the contestants from shows like The Biggest Loser, where they are just-- oh my goodness, it's crazy. This insane amount of weight loss you do in such a short amount of time.” But the after stories, and hopefully everybody seen some of those, it is not good. The majority of the time, it's not good. We do have those smaller percentage of long-term success stories. The way to go about that, we have to have a level of grace and intelligence and understanding how our cells are working really, especially our fat cells.

With that said, this is not to say that we can't lose fat with speed and with grace, but it's getting a better understanding on how the processes work behind the scenes and fueling our bodies with the right nutrition to counterbalance these hungry, hungry fat cells. I’m thinking about that game, Hungry Hungry Hippo, when I was a kid, I don't know if that's still a thing. To counterbalance that, with the right nutrition, because this is a big takeaway too, is that chronic nutrient deficiency leads to chronic overeating. One of the biggest driving forces of our hunger-related hormones, it's not just one, it's not just ghrelin, there's many others. We talk about several in the book. We have to make sure that we're providing our bodies with the raw materials that it needs to do the processes of fat loss. We have to provide those nutrients or, again, we're going to evoke hunger. There's nothing more challenging than trying to lose weight, trying to lose fat, when you're chronically hungry. It is one of the worst things that have been inundated in our culture. We've been inundated with this idea.

I've had so many people come in that they don't feel that they're doing a great job because they're not hungry. We're inundated with this idea that if you're hungry, it's working. It's this idea of starving yourself so that you’re successful. That actually came from the person who really indoctrinated our culture with the science of well-- lack of science, let me be clear. With the science of calories. We go through the history of calories. This is Dr. Lulu Hunt Peters. She actually encouraged people to seek out hunger, like you should be hungry. This is the time of food rationing as well. She said that every hunger pang you feel, you should have a double joy, knowing that you are saving the hunger pangs in someone else. You're sacrificing, and making yourself hungry, you're losing weight, feeling great, hungry, but you're going to be helping your nation and losing weight as well. The sidebar that a lot of people-- she struggled with her weight her entire life as well. She's the person who really integrated calories into our culture. This was the shift of taking food as this multifaceted dynamic entity, because food truly does, as we talked about earlier, food becomes you. It becomes your brain cells, it becomes your heart cells. Your heart is made from the food that you eat. Your blood flowing through your veins is made from food, and water, of course. This stuff matters, and it's so powerful and dynamic but this is when the shift of taking food and turning it into numbers took place, which is incredibly tricky, incredibly scary and sketchy.

She said in her book, and I went back and read these old-fangled writings-- she sold over two million copies of this in the earlier part of the 1900s. At that time, basically everybody who can read got this book. She said, “We will no longer eat food, you will no longer eat food, you will eat calories of food. With that, you'll no longer eat a piece of bread, you eat 100 calories of bread. You'll no longer eat a piece of pie, you’ll eat 100 calories of pie.” When we made the switch to thinking about food in terms of numbers, we lost the metabolic impact that food has on everything about you, every single bite of food you eat. We've got entire fields of nutrigenomics and nutrigenetics looking at how food literally determines your genetic expression, and how your genetic expression determines the food you should be eating. None of that is taken into consideration. We start thinking about food simply in terms of math, but not to say that the calorie system can't be useful, but there are seven clinically proven things that control what calories do in our bodies, those are the epi-caloric controllers. That's a lot, and it's such a great question and thing for us to think about in relationship to all this.

Ultimately, it's just about us really understanding some of this stuff in a way that makes sense, being empowered, helping ourselves to be the best version of ourselves, helping our families, and really at a time when we need it most to really help our communities to get healthier.

Melanie Avalon: This is so incredible. I’m so glad that's where you took it in your answer because that was something I wanted to ask you to talk about, was the calorie model and how it got infused with being the ultimate answer and picture and also this morality that got infused in it, and it's just crazy. Listeners, I know we've made Eat Smarter seem like a very scientific book. It also has so, so much about mindset and society and relationships and how all of these factors affect not only your diet and your body weight, but also your goals, your dreams, your visions. It's really just an incredible book. Actually, the last question that I always ask every single guest on this show, it's just because I realized more and more each day how important mindset is surrounding everything. So, what is something that you're grateful for?

Shawn Stevenson: The first thing coming to mind-- ah, and the person who just popped in here, I’m grateful for my wife, my best friend. I think that one of the things that our genes really expect us to do is to have connection and community and love. Love is one of those things where me being a scientist, it can seem very just on the fringe, but truly the expression of love, the expression of togetherness. The former US surgeon general prior to the pandemic, he had a book coming out, we're going to have a conversation about it, but look with all the science on how loneliness is the greatest epidemic we're facing as humanity, especially here in the United States and the data was just so shocking, and then COVID hit.